|

Can Westerners really claim most of the credit for this? Bluntly, yes. The unprecedented rise and global diffusion of the scientific method, the industrial revolution, and democratic capitalism from the mid-eighteenth century that coincided with those improvements in global living standards has to get the majority of the credit, and those came from the West. As Charles Murray explained in his book Human Accomplishment, “What the human species is today it owes in astonishing degree to what was accomplished in just half a dozen centuries by the peoples of one small portion of the northwestern Eurasian land mass.”

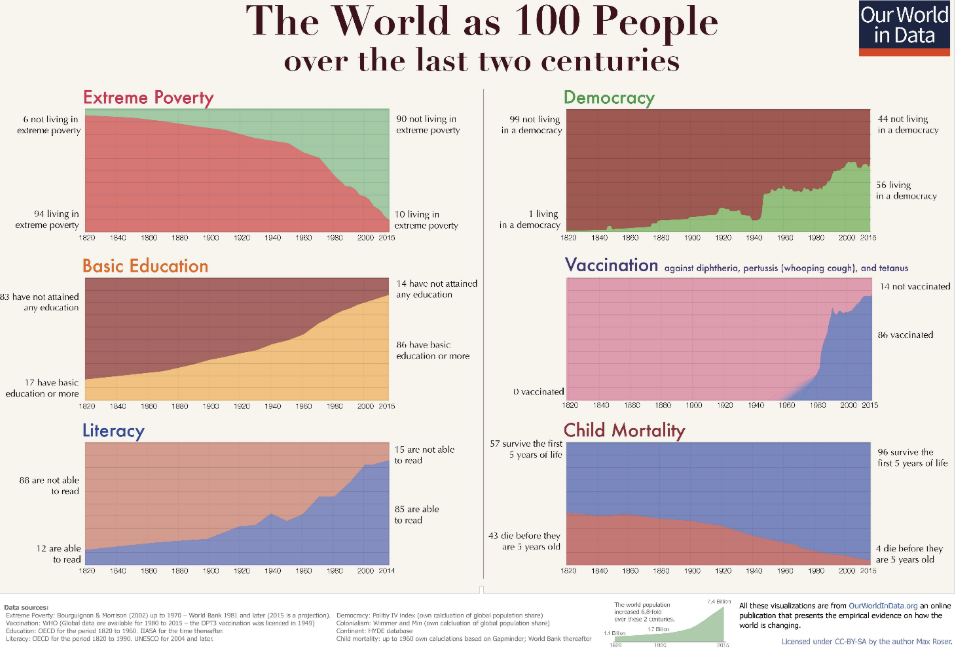

There have, after all, been many empires and many slaves throughout world history, but none of them produced Western innovations like the industrial, atomic, genomic, space, computer, and green revolutions; most of modern engineering and medicine, from vaccines and antibiotics to transplants and chemotherapy; and the bulk of modern communications, transportation, and consumer white goods technologies. Without these advances our species wouldn’t have gone from a world in which, as of 1820, 90% of the global population lived in extreme poverty to one in which only 10% do so today; or from 88% global illiteracy in 1820 to only 15% today; from 0% global vaccination against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus then to 86% today; from 43% of the world’s children dying before age five then compared to only 4% today; and so on.

Thanks to its hugely disproportionate contributions to scientific and technological innovation and their globalization, the West has more than made up for any harms historically inflicted on the rest of the world through slavery and imperialism. As a result, there is in fact a net developmental benefit flowing from the West to the Rest, not a net continuing harm as assumed by demographic retributivists. There is as such no unpaid debt to be discharged.

Finally, there are glaring moral problems with the sort of collective guilt that it presupposes. On this point, all members of a wrongdoer’s group, including those who we would not hesitate to call civilians and even children, can be held responsible for a wrong committed by any one of them. On the version required here, this is true even if the wrongdoers in question died many generations ago, and even if the group membership in question is one defined by race rather than, say, beliefs or citizenship. As such, the argument goes powerfully against the grain of what has hitherto been seen as a tremendously important form of moral and legal progress, namely our evolution beyond ruthless practices of collective sanctioning in times of war and peace.

There are at least two sorts of weighty reasons to think we should keep the taboo against collective punishment intact. The first holds that it is wrong because its general acceptance would have negative consequences overall. These in turn would take at least three forms: its intended beneficiaries would be harmed because it saps their agency and stokes painful feelings of envy and resentment to continually attribute all of their problems to somebody else; its intended victims would of course be harmed by design, ultimately with statelessness, expropriation, and in the very long-term even ethnic extinction; and both of them would be harmed by the retaliatory reaction it will predictably elicit from its intended victims.

The second sort of reason holds that even in the unlikely event that a world with generalized blood-guilt had positive effects overall, we should reject it anyway because it violates one or more of the moral rights of those who are so punished. In this case the right in question is obvious and familiar to all heirs of the Anglo-American legal tradition: the right of an individual not to be punished for things for which he is not casually or morally responsible.

One might object that this right wouldn’t be violated if the individual consented to accept responsibility for every historical act or omission of their race, but as an argument for immigration-as-retribution any such appeal to consent fails both because it wouldn’t then really be an argument for collective responsibility at all, and because it cannot on any reasonable interpretation of the facts be said to actually apply to anyone living. It might alternatively be objected that the right isn’t violated if all group members have, in some way, contributed to the group’s wrongdoing. But while some contemporaneous group members could be considered aiders and abettors for providing political or economic support, or not protesting vigorously enough if we (say) reintroduced slavery today, this wouldn’t be true of all members. And the contributions of many of those who are causal contributors would be minimal and indirect. And in the case of those born long after the wrongs in question, they cannot plausibly be considered causal contributors at all, let alone to a degree sufficient to justify the degree of harm involved in unlimited open borders. One must therefore conclude that this argument also fails, as the degree of punishment imposed should be proportional to the degree of one’s causal contribution and that requirement has clearly not been met in the case of inter-generational responsibility for historic offences.

In conclusion, then, demographic retributivism is a rotten argument even when presented in its best possible light. Moreover, its exponents for the most part don’t even appear to believe it themselves, instead using it as pseudo-moral camouflage for the bigoted or venal ulterior motives or pathological guilt complexes that really move them.

What Can Be Done?

First, we should avoid artificially stimulating racial envy and resentment. As seemingly permanent features of the human condition, we cannot eliminate them altogether, but we can at least remove direct incitements to them such as critical race theory in schools. As distance can diminish the effects of envy, we should also be wary of a regime of forced and micro-managed association in the name of compulsory diversification, as this makes it impossible to achieve. And, given that by far the best way to overcome envy is to have goals of one’s own, a rigorous traditional pedagogy, and meritocratic culture focused on achieving through one’s own efforts will help dispel the distraction of invidious comparisons from which ressentiment springs.

Second, we should not take too literally the accusations about slavery and colonialism constantly cast in our teeth by postcolonial and critical-race theoretic historiography. No one would care about the sins of the West’s great-great-grandfathers, real or imagined, if they were not still more successful than other parts of the world today. It is observed superiority that inspires resentment, not the wrongs of past centuries, which are at most post facto ways of rationalizing resentment. We should never forget that they are mining history selectively with this goal in mind, not presenting a balanced and dispassionate accounting of the West’s past.

But, perhaps the most important lesson for us to learn, third and finally, is the futility of appeasement and the need for demographic prudence. Owing to the enduring power of ressentiment in human affairs, it is unlikely that those who insist on considering themselves victims will ever be persuaded by the arguments presented here, not least because this would require them to take a greater share of the responsibility for their own problems. To the extent this is true, it finally suggests that we should think long and hard about the wisdom of allowing so much immigration, so quickly, as to give the proponents of demographic retribution the political power to make their “imagined revenge” a reality. The posterity of all groups who see the West as their permanent home will thank us for our caution.

Lest this seem alarmist, remember finally that there is, sadly, a long tradition worldwide of successful but less numerous groups being expropriated and scapegoated by more numerous but less successful groups; Jews, Armenians, and the Chinese diaspora in south-east Asia are but a few prominent examples. Multiethnic democracies in which political power is determined by the number of people you can get out to vote, and in which voting behaviour is mostly split along ethnic lines, are particularly at risk. Whether we face a future of mass interracial score-settling against such groups or something resembling a functioning multiethnic democracy will in substantial part depend on how we deal with demands for immigration as punishment.

|