The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has released its demographic profile of the incoming class of 2028. This is the first class of students to be admitted after the landmark 2023 Supreme Court case Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard ended the admissions practice of affirmative action. Affirmative action was a policy that allowed colleges and universities to consider a candidate’s race when constructing an incoming student class. For decades, the policy was intended to artificially inflate the proportion of African-American students at American institutions of higher learning beyond the percentage they would obtain if grades and standardized test scores were the only factors considered.

So, how does the incoming MIT freshman class stack up against previous classes?

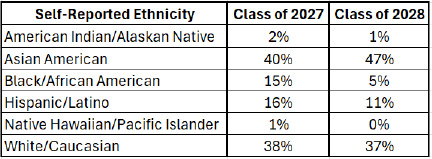

As predicted, the proportion of Black/African-American students in the incoming class dropped precipitously, from an average of about 15% down to 5%. Other racial minority groups also fared poorly. Hispanic and Latino students dropped from 16% to 11%, Native Americans dropped from 2% to 1%, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders dropped from 1% to 0%. The share of White students remained roughly static, dipping slightly from 38% to 37%. The real winners at MIT are Asian-Americans, who jumped from 40% to 47% of the incoming class. This graph shows the racial makeup of the incoming class compared with the previous year. (Note the percentages do not add up to 100%. This is because students are allowed to submit multiple racial identities.)

Racial makeup of the incoming class compared with the previous year

Within minutes of the New York Times publishing the data, there was outrage. Many liberals were astonished to see decades of work towards racial equity evaporate in an instant. The Right previously hailed the SFFA ruling as a return to meritocracy, but some struggled to defend the resulting racial wipeout. Ordinarily, I would be inclined to cheer the results, and especially to cheer the demise of naked racial preferences in college admissions. This situation, however, has got me thinking more deeply about the problems that face college admissions, and about diversity within elite institutions at large.

There may not be a good solution to the college admissions conundrum. To explain why, we need to talk about the SFFA case.

SFFA v. Harvard

The Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (SFFA v. Harvard) case was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that addressed the constitutionality of race-conscious admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. The antecedents to the case stretch back to the origins of affirmative action itself. Affirmative action as a concept was conceived separately from the academic context as one of many tools to address the inequities of systematic racial discrimination in government hiring. The first use of the phrase “affirmative action” dates to an Executive Order signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 that instructed government contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and employees are treated [fairly] during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin”. That commandment was gradually extended to government hiring as well. What became a tool for expansive racial quotas in admissions began as a policy of colorblindness in government hiring.

Affirmative action gradually expanded to collegiate admissions practices. After Brown v. Board of Education (1954) ended racial segregation in schooling, a trail of Supreme Court cases transformed affirmative action from a right of minority students against discrimination into a positive ability of universities to consider race as a salient characteristic in admissions. In 1968, the Supreme Court ruled in Green v. County School Board that school districts had an “affirmative duty” to desegregate. This required them to come up with plans by which schools would become properly integrated. So far, so good, but one can already see the primordial germ of modern affirmative action in development.

Over the course of the 1960s and ‘70s, school integration proceeded at an intolerable rate. The nation’s liberals came to increasingly accept the not unmerited thesis that black students continued to be held back by the legacy of racial discrimination. Consequently, black students needed and deserved an affirmative edge to tilt the scales in their favor. In time, this would jumpstart the drive towards full equality. In 1978, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke that using race as one of several factors in college admissions did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Court prohibited explicit racial quotas, but found that racial diversity was a compelling state interest.

Finally, in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), the Court ruled on the penultimate challenge to affirmative action. In that case, the Court abandoned its hesitation in Bakke and explicitly endorsed the use of race and affirmative action in admissions policy. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor delivered the opinion of the Court, writing that the Constitution “does not prohibit the.. narrowly tailored use of race in admissions decisions to further a compelling interest in obtaining the educational benefits that flow from a diverse student body”.

Over the course of fifty years, affirmative action evolved from a colorblind policy in government hiring into a full-throated defense of racial preferences in the admissions process to American higher education.

This brings us back to SFFA v. Harvard. Affirmative action remained a highly contentious issue, not only because it slanted the scales against white applicants, but because it harmed educational opportunities for other minority groups, namely Asian Americans. One of the central claims in the SFFA case was that Harvard’s admissions policies were discriminatory against Asian Americans. Asian Americans score very well on objective metrics like standardized test scores, higher than white students, and are vastly overrepresented in American higher education, especially at elite universities. At only 6% of the total U.S. population, Asians comprised over 25% of Harvard’s undergraduate class in 2022 before the SFFA ruling. This proportion would be even larger were it not for Harvard’s use of subjective criteria to artificially suppress the number of admitted Asian students. The SFFA case revealed that Harvard was using traits such as likability, courage, and kindness to penalize Asian American students compared to applicants from other racial groups. The cumulative result was that Harvard had wittingly racially stereotyped Asian applicants as scoring lower on these criteria than other races.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

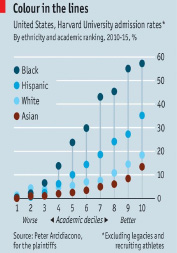

According to Harvard’s own admissions data, black and Hispanic applicants at every academic decile had dramatically higher chances of admission than white and Asian students at those same deciles. A black student in the top decile of academic performance was five times more likely to be admitted than an Asian student and almost thrice as likely as a white student in the same decile, despite black people only accounting for 14% of the U.S. population. Likewise, a black student in the 5th decile of academic performance had a 25% chance of admission. An Asian student in that same decile had almost no chance at all. These are not small admissions bonuses being provided to certain favored races, but enormous weights on the scale in their favor.

Affirmative action rose to prominence because it was seen as one tool among several to address the lasting effects of racial discrimination on the black populace. The logic of that argument could not stand up to scrutiny in an increasingly diverse, multiracial America. How is it possible that an incalculable amount of perks and benefits given to the black community through decades of racial preferences and DEI policies have failed to produce sustainable improvements in outcomes and achievements? How is it that other racial minorities, many from impoverished backgrounds, broken or underdeveloped countries, with perhaps even greater claims to adversity, have been able to succeed so much despite formalized academic penalties applied against them? How is it fair to give entire races a systematic benefit in admissions despite not all applicants being subject to the same level of adversity? What do we do for white or Asian students who grew up in even greater misery? Affirmative action has no answer to these questions. Indeed, affirmative action by its nature can never answer these questions.

What is to be done?

I think affirmative action was an indefensible policy. Its own incoherency was made manifest by the rise of a multiracial America. It was one abominable thing to discriminate against white students to give black students an advantage, but such a scheme was unsustainable when large cohorts of other racial minorities were introduced to the system. Such conditions proved affirmative action was nothing short of an elaborate racial exchange rate system. Still, the demise of affirmative action has proven one thing: nobody is happy.

This is because everybody has a different idea in mind of what a university is supposed to be and do. Depending on what one thinks of as the purpose of the university, the ideal admissions policy follows. There are at least three admissions models that come to mind most readily: the elite model, the meritocratic model, and the national model. I will explain and address the deficiencies of each.

The Elite Model

The elite model of the university and admissions holds that higher education is the formative arena for the nation’s, or perhaps the world’s, future ruling elite. These are the people who will one day govern the institutions that structure and shape the daily lives of billions of people. This is also the place where the future elite will meet each other and form lifelong bonds. Practically everyone recognizes this property of higher education, especially elite institutions. We all know that every year, Harvard and Yale will produce a class of talented lawyers, several of whom will clerk at the Supreme Court, and who will in turn be considered for judgeships, elite legal positions, and in all likelihood even serve on the high court itself.

Whether or not these elite institutions actually select for and cultivate the best and the brightest is a second-order consideration to the immense prestige and status they bestow on admitted students. A ruling elite can more or less be forged out of substandard material. There is no ironclad relationship between pure talent and elite status. Consequently, the future elite is somewhat self-determined. The current elite has a large hand in picking and choosing tomorrow’s elite, and the current elite is, for the moment, obsessed with ensuring racial and gender diversity among the future elite, no matter the cost. The current elite believes evidence of disparities is evidence of discrimination. If the current elite is overwhelmingly white and Asian, it is because of systemic inequities that obstacle other racial minorities from assuming their rightful place. Thus, with the foregoing elite model of higher education in mind, the university is the perfect venue to rectify persistent disparities.

The pitfall of this model, and what makes abandoning it so dangerous, is that the current elite abhors true meritocracy. A drop in the proportion of black and Hispanic students at elite institutions from their artificially elevated levels to near zero, as is hypothesized, would be cataclysmic. The current elite can’t stand the thought of disadvantaged minorities utterly disappearing from elite higher education. Furthermore, I think most Americans, generally kind-spirited, can’t stomach the thought either. The difference between the two groups is that the current elite have the power to bend the institutions to their will. They are already trying.

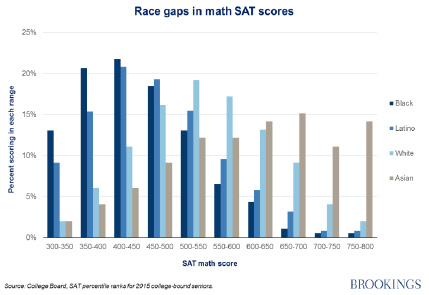

Let’s return to MIT’s incoming class profile. The black proportion of the student body fell from 15% to 5%. Still, even this low number is evidence of affirmative action at play. The percentage of SAT test-takers scoring above 1500 who are Asian is 58%, 35% for whites, and 1% for blacks. Thus, one might expect that for every fifty-eight Asian students, there would be one black student. If we look at the data for SAT math scores by race, black students barely show up at all in the top three score deciles. In the absence of affirmative action, there should be basically no black students at MIT.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

Let’s examine a more obvious case: over at Harvard, the admissions data show a different story. The percentage of black students fell this year from 18% to 14%, a much smaller decrease than MIT. Harvard often shares the top position in the rankings with other prominent institutions like MIT, Yale, Princeton, and so on. These universities aren’t slouches and they routinely collect the cream of the crop of students. A decline from their overrepresented 18% to 14% brings the black student population at Harvard in line with the national proportion of black Americans, but it means black students are still dramatically overrepresented for their scores. In their own testimony, Harvard argued that ending affirmative action would obliterate the black and Hispanic student population, and yet they hold on. The Hispanic proportion of the incoming class even grew this year.

So, either one of three things is happening: Harvard is lying when they said they have ended racial preferences in university admissions, Harvard lied when it said such a racial composition was impossible without affirmative action, or Harvard admitted and enrolled nearly every single black student in the top decile of academic performance. The latter scenario is statistically improbable, but it would still rely on considerable affirmative action. The second scenario is unlikely as well; Harvard was being honest when it said that ending affirmative action would all but eliminate the black and Hispanic student populations at their university. The most likely scenario is the first, that Harvard never ended affirmative action and continues to give strong consideration to race in their admissions process.

The point is that the elite will not tolerate an un-diverse student body and won’t give up with affirmative action so easily. They will do almost anything, including breaking the law, to maintain their racial exchange system. This is what makes the elite model so dangerous: liberals are aware of the threats to their power and will now close ranks to preserve it against even the law itself.

The Meritocratic Model

The second model we will discuss is the meritocratic one. Its definition and the arguments for it are relatively intuitive: admissions should be driven by a pursuit for the best candidates that a given university’s academic stature can acquire. We want to cultivate the best of the best, and that task requires selecting students based on merit, achievements, and aptitude. The best objective metrics available to do so are standardized tests and grades, with extracurriculars, essays, and other smaller subjective metrics further influencing the calculus. This process will help sort students into colleges and universities most suited to their respective capabilities.

The meritocratic model is the obvious antidote to the elite model. It posits there is a crucial distinction between a constructed elite and a genuine intellectual elite. Affirmative action is not only counterproductive, but also morally reprehensible as it blocks many talented and deserving applicants from the universities that would best foster their talents because they are members of the wrong race. And the meritocratic model is rooted in objective and convincing arguments for its legitimacy.

The only problem is that most people don’t like what pure meritocracy looks like in practice. Let’s take the meritocratic argument to its logical conclusion. If objective metrics and extracurriculars were all that mattered, the top ten American universities would be roughly 60% Asian and 35% white. Remember, this is in a country with an Asian demographic totaling only 6% of the national population. Below the top ten, we would start to see whites, blacks, Hispanics, and other smaller racial groups start to appear in larger proportions, but there would still be a large showing for Asian students. It wouldn’t be until several dozen colleges down the rankings that we would start to see significant black and Hispanic representation. Finally, the lower half of universities would have large black and Hispanic demographics, but very few Asians and only some whites.

This is an accidental racial caste system enforced by the soft oppression of test scores and grades. It would be rational, but it would hardly be tolerable to most Americans. Americans believe in the equality of all races and the equality of opportunity. Those philosophical principles are plainly incompatible with a system that relegates some races to the bottom. It would also be intolerable because most Americans, who are white, would be bewildered to find that their top institutions are more than half Asian. This system would almost certainly lead to intense racial strife.

The National Model

The final model, which I think is implicit more often than it is explicit in arguments about the role of the universities, is what I shall term the “national model”. The unspoken assumption undergirding the national model is that colleges and universities should broadly serve the interests and welfare of the American people and their children. This is the same principle that supports many critiques of DEI and wokeism, which are plainly antagonistic to America and American national identity. In the context of admissions, the national model holds that institutions of higher learning should admit almost exclusively Americans, coupled with the belief in racial equality, and you get American universities that look generally like a representative sample of the nation at large.

I encounter this unspoken argument most frequently when talking to parents of students applying to in-state public schools. Take Virginia Tech, for example. Residents of Virginia will often make the claim that Virginia Tech, a state school that receives state taxes and carries the commonwealth’s name, has an ethical and fiduciary duty to admit primarily Virginians. The incoming freshman class at Virginia Tech is a little more than one-third from out of state. Within the engineering department, for which the university is known, almost half the students are from out of state. These students pay more in tuition, but that’s not the point. The out-of-state population for the incoming class numbers 10,739 students, and unwitting proponents of the national model argue those seats should be given to Virginians instead. Such a shift might lower the academic rigor of the university, but without more granular data, it is difficult to know for certain.

I think there is an important lesson to be learned from recognizing higher education’s fundamental civic purpose. A national model for state schools could go some way towards resolving the admissions conundrum, but it would be far from perfect. State public schools could admit classes that are generally representative of the demographic makeup of their respective states. This would have the effect of minimizing the out-of-state student body and would ensure greater representation than the meritocratic model, but it would still be unmeritocratic in many cases like at elite state schools. Private national universities could follow suit by admitting classes that are representative of the nation as a whole. But this runs afoul of the criticisms of affirmative action. Such a representative model would still require significant degrees of racial prioritizing to work. It would also severely limit opportunities for Asian Americans especially, who would be effectively locked out of elite institutions by virtue of their small population size.

In sum, there is no solution to the college admissions conundrum that would make most people happy in a way that would resolve the bitter fight over higher education. Affirmative action has proven to be egregiously and systemically racist. The elite model goes hand-in-hand with affirmative action and produces classes of students from which only a portion of whom can be properly called “elite”. The meritocratic model addresses the vices of the elite model but replaces it with a likewise intolerable system. Few Americans will gleefully cheer on the total disappearance of entire races from elite educational institutions. Only a wholesale shift in American racial thinking would lend that model any stability. The national model seems like a compromise that might make parents happier in general, but it too relies on significant amounts of racial tampering and would likely reduce educational outcomes for many unlucky students. It therefore runs afoul not just of the criticisms levied on the elite model, but on the meritocratic model as well.

What is clear is that the diversification of the American population has opened a can of worms for American higher education. Conventional theories about past injustices, oppression, and privilege no longer make sense in a nation that isn’t strictly divided between black and white. There may be some undiscovered solution out there, but for now, I fear we will be litigating this issue for years to come.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.