Over the summer, Sweden’s justice ministry released a report on immigration that may well go down as a landmark in Europe’s demographic history. It trumpets the fact that, for first time in more than half a century, the country now has net emigration (i.e. more people leaving than arriving). Although this turns out to be not quite statistically true – more on this shortly – the fact that they are even close to achieving net emigration, and proud of it, is a striking turnaround for the erstwhile “humanitarian superpower”. The report also boasts that the number of asylum applications is at its lowest since 1997, in contrast to much of the rest of western Europe. “We are in the midst of a paradigm shift in our migration policy”, Migration Minister Johan Forssell declared. The Guardian agreed: the Swedes have gone “from open hearts to closed borders”, it noted with disgust.

Despite the Guardian’s pique, this shows that democracy is functioning in Sweden, as even that nation’s politicians belatedly turn away from a path of violence, social decay, and economic insolvency. What prompted this shift? How has it been achieved? And what does it tell us about the wider evolution of European approaches to legal and illegal migration?

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

The Backstory

Sweden’s international reputation used to be a sort of gold standard of competent leftism: an egalitarian, big government welfare state that produced excellent results. Conservative critics long suspected that it was too good to be true, resting on foundations which would either be eroded by sustained progressivism or couldn’t easily be generalized to more diverse countries, or both. But decade after decade, the Swedes defied their predictions of doom.

No longer. Thanks to high levels of mass migration from the developing world, mostly the Middle East and Africa, Swedish progressivism was mugged hard by reality over the last decade. The country is now better known among conservatives and even some left-wing parties such as Denmark’s Social Democrats as a cautionary tale about the social chaos that can follow from allowing too much demographic change, too quickly.

In 2015, when Angela Merkel unilaterally opened Europe’s gates to over a million men from the Middle East, the Swedish government was her most enthusiastic follower: “My Europe does not build walls!”, thundered Stefan Lofven, the Social Democratic Prime Minister at the time. He threw open the borders to any asylum-seekers that could reach Sweden, taking in 160,000 that year alone (the highest per capita in the EU). More than 770,000 people have immigrated to Sweden from countries outside the European Union and European Economic Area (EEA) over the last dozen years. By 2022, about 20% of Sweden’s 10.6 million inhabitants were foreign-born, more than double the figure for 2000, many of them from Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, and Iran.

The cost of that generosity has been immense. Once an enviably safe country, Sweden has seen crime surge since 2015. It now has one of the highest per capita firearm homicide rates in the EU. The country’s cities are plagued by bomb and grenade attacks, something that was unheard of only a few years ago. The rise of serious crime has been driven by gang violence, which is now so bad that its Scandinavian neighbors join forces to try to prevent it from spreading to their territory. As I noted in a previous post, these problems are highly disproportionately concentrated among the non-Western immigrant population and their descendants, so much so that a recent study found 85% of street gang members and 94% of organized-crime syndicates have a first or second-generation immigrant background.

Alongside soaring levels of crime, disorder, and gang activity more reminiscent of pre-Bukele El Salvador than Scandinavia, the country’s abrupt demographic transformation has also led to a deteriorating economy. With much higher rates of unemployment among those born abroad alongside lower average incomes, the situation has widened Sweden’s wealth inequalities and threatens the solvency of its generous cradle-to-grave welfare system. Migrants and their children are a net fiscal burden on the Swedish state overall, consuming around 58% of all social welfare assistance in the country despite native Swedes still constituting 65% of the population. The non-Swedish and non-European population is resultantly expected to more than double the burden placed on the country’s pension system.

The massive influx has also had such a negative impact on Sweden’s educational performance that the number of people classified as illiterate in the 10.6m strong nation is expected to exceed 800,000 this year. “If this trend continues, we risk having an entire generation of young people who are effectively functionally illiterate”, warned Minister of Education Johan Pehrson and Minister of School Affairs Lotta Edholm in a recent article. The newspaper Expressen discovered that the country cheated on its PISA school tests (an international league table) by altogether removing foreign-born and Swedish-born immigrants from its sample so as to keep its ranking up. And this is all in addition to the residential segregation, social exclusion, and diminished solidarity that the huge migration wave has brought to a society once famous for its public spirit.

The Swedish ruling class seem to have finally come around to the reality of the situation: Sweden cannot continue to function as a stable, cohesive, successful, or solvent society if these trends continue. Since assuming office in October 2022, a centre-right minority government led by the Moderate Party and sustained with parliamentary support from the national populist Sweden Democrats has accordingly made it its main task to not just decelerate, but partially to reverse, the progressively worsening damage exacted by the immigration policies of its Social Democratic predecessor. Even they are now singing a different tune in opposition: “The Swedish people can feel safe in the knowledge that Social Democrats will stand up for a strict migration policy”, Magdalena Andersson, their current leader, said in December; “free immigration is not left-wing”.

Immigration and asylum policy has changed course accordingly. Last year the government announced a complete overhaul of the system, with a package of reforms aimed at turning Sweden from one of the most permissive countries for irregular and legal migration into one of the toughest, up to and including payments for the voluntary repatriation of naturalized citizens. Let’s take a look at the details.

Illegal Immigration

A government committee is currently putting together a law that will require the 1 million plus people who work with or for the Swedish state to report any contact with an illegal immigrant to Swedish authorities. The proposal – derided as a snitch’s law by its critics – was introduced last year as part of the so-called Tidö agreement, a pact outlining the terms for cooperation between the three right-wing parties in the government and the Sweden Democrats. They plan to present their findings to the government by the end of November.

Once enacted, the duty to report could result in many of the over 100,000 illegal immigrants currently thought to reside in the country being reported to police and earmarked for deportation. The government has also ramped up the number of return centers, to prevent illegal aliens from going underground after being ordered to leave the country.

Legal Immigration

Sweden have cracked down on low-skill legal immigration, too, primarily by restricting work permits to economic migrants who earn at least 80% of the Swedish median wage. This has been coupled with reforms to make chain migration of family dependents harder, the introduction of new requirements for migrants to measurably integrate into the economy and society, and plans to revoke the residence permits of those who commit crimes or do not have an “upstanding way of life”.

The government has also implemented stricter asylum legislation, which seems to be working: in 2015, Sweden took 13% of all asylum seekers in the EU, but, in 2024, it is predicted to take just 1%. The Ministry of Justice attributed this to a decline in the number of people seeking asylum in the country, coupled with a decline in residence permits issued. That this change is not down to wider European trends seems evident, as overall numbers of asylum seekers in the EU remain high, making Sweden’s domestic policy achievement that much more impressive.

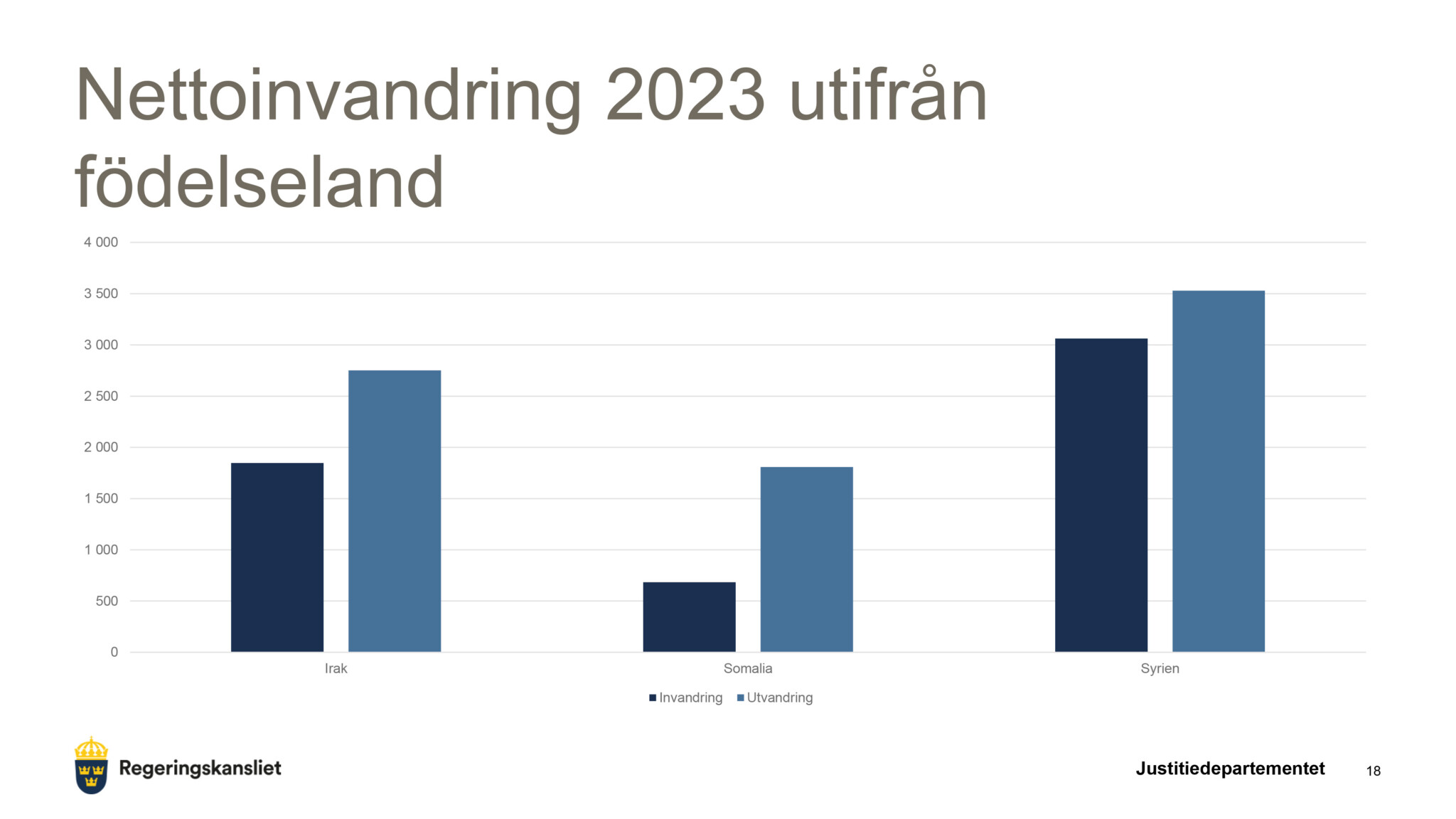

Taken together, these measures help explain the report published on August 9th claiming that Sweden experienced net emigration in the year up to May for the first time in 50 years. It says this was primarily driven by higher rates of emigration than immigration among people from Iraq, Somalia, and Syria as you can see in the chart below, where the taller light blue bars represent emigration levels and the dark blue ones immigration levels from those countries.

This claim must be taken with a pinch of salt. Statistics Sweden subsequently pointed out that, once adjustments to previous years’ figures made as a result of ongoing checks on Sweden’s population register were stripped out, the country still had modest net immigration of around 5,000 people in the first half of the year: 41,439 people immigrated over that period compared to 36,404 people who emigrated. The “net emigration” headline is the result of a lag in the tax authority’s de-registering of an additional 7,700 people reclassified as no longer living in the country. “Sweden does have a relatively low net immigration, but in reality, more people still immigrate to Sweden than emigrate from it”, the immigration skeptical outlet Samnytt concludes. So, the reality is somewhat less surprising than the report initially suggested. Nonetheless, the Swedish government is correct to regard these figures as marking a “paradigm shift” towards a substantially reduced inflow of non-Swedes and non-EU migrants that promises to make Sweden a more peaceable, cohesive, and sustainable country over the long term.

Remigration

Perhaps even more significant is the proposal to pay legal immigrants and naturalized citizens to return to their countries of origin.

Currently, the Swedish state offers would-be emigrants $960 plus travel expenses to go back to their homelands or another country where they have the legal right to reside. AFP News now reports that it is planning to increase repatriation payments dramatically to $34,000 dollars per person, starting in 2026, without any means-testing. This is a significant sum of money: it represents 11 times the average annual income per capita in Syria, for example, and 6 times the average annual income in Iraq. It is also significantly higher than the average migrant income of $29,400 in Sweden (a figure inflated by generous welfare benefits). In order to ensure that the recipients of such payments do not travel back to Sweden with a different identity, the biometric data of all remigration recipients would be recorded.

It is difficult to say how many people will take up the offer, although a poll conducted by the website Alkompis showed that 77% of those questioned were not interested in remigrating, even for the increased amount. Still, 15% were interested. Even if only a fraction of that number ultimately did so, it would amount to tens of thousands of people. Combined with plans to limit state benefits to migrants covered by EU free movement rules, this program therefore stands a good chance of getting Sweden to net emigration for real in the near future.

This is a significant development. Although other European countries also offer grants as an incentive for migrants to return home, they are much smaller: $1,400 in Norway, $2,800 in France, $2,000 in Germany, and $15,000 in restrictionist Denmark. Sweden, pushed by the Sweden Democrats, has now become the first nation to put a serious pot of money behind repatriation (tens of millions of dollars have already been set aside) so that hundreds of thousands of legal migrants and naturalized citizens would be better off spending their payments back home than by staying.

The Danes Were Right

It’s all the more interesting given that this is Sweden we’re talking about, hitherto a progressive pin-up with one of the highest levels of gender equality in the world, a generous welfare state, and a leader on environmental issues. If even the Swedes are willing to admit that the progressive/neoliberal consensus on mass immigration as an unalloyed good has failed, this suggests it can be jettisoned elsewhere in the West as well.

An alternative can be found right next door in Denmark. Sweden and its smaller neighbour diverged in the early 2000s on mass immigration policy, with Denmark taking the world lead in coming up with smart ways to measure the impact of immigration, to restrict numbers, and to ameliorate its social impact. Faced with Merkel’s influx of refugees in 2015 and 2016, the Danes introduced a new temporary protection status that could be withdrawn when conditions in home countries improve, a measure that has already led to the return of Syrian asylum seekers. In 2016, authorities were granted the right to confiscate valuables from new arrivals to fund their stay. New laws sought to limit the number of non-Western people living in any given neighborhood to prevent the emergence of ghettos. A plan to deport asylum-seekers to Rwanda so they could be processed there was mooted. Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, of the Social Democrats, has touted a vision of “zero” asylum seekers arriving to Denmark outside the United Nations resettlement system, a strategy which helps to explain why, aside from Malta, she is the only left-of-centre leader in Europe whose party is both in government and ahead in the polls.

They did all of this while their Swedish neighbors were going in the exact opposite direction, setting up a clear Denmark vs. Sweden test of which immigration policy works better: the picky “requirement model” of the Danes, or the generous “rights model” of the Swedes? The results are unambiguous. By updating their ideology for the demographic realities of the 21st century and being unflinchingly data driven, the Danish government shielded its people from the heavy fiscal, social, educational, and crime costs that befell the pathologically altruistic Swedes. It took the Swedish elite until after 2015 to admit the Danes had won the argument, and until 2022 to elect a government committed to changing course. But now they have one, thank goodness, and it is already achieving impressive results. Let’s hope that other Western governments don’t insist on learning from painful experience before heeding the lessons of Danish common sense and the Swedish paradigm shift.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.