A criticism of the first Trump administration, made by those willing the once-and-potential-future President’s success, was that its agenda was too easily thwarted. He didn’t build the wall; allowed pandemic policy to be dictated by Dr. Anthony Fauci, while the National Institute for Health funded Gain-of-function research in Wuhan; and had his hands tied by the Russian collusion investigation and two impeachments. Team Trump faced frustrations by both neoconservatives in the Republican party (or “Uniparty”) and those unwilling to carry out their democratically elected mandate in the administrative state (or “Deep State”). Among the worst examples were:

- Military officials misled Trump about the number of American troops stationed in Syria, to prevent a full withdrawal.

- Text messages between FBI agent Peter Strzok and FBI lawyer Lisa Page, during their extramarital affair, insisted that Trump would “not ever going to become president, right? […] No, No he’s not. We’ll stop it”.

- Over fifty other intelligence officials signed a letter, calling the Hunter Biden laptop a “Russian information operation”, despite knowing it to be true, just before the 2020 election.

Hence why the likes of the Heritage Foundation proposed reforms to how unelected bureaucracies are staffed and structured with Project 2025. The Trump campaign has since disavowed this, after the Harris camp became hyper-fixated on it as a plot to jettison the Constitution and end America as we know it. I covered the contradictions between Democrats’ talk and action on democracy here.

However, there is one weak spot that Trump has yet to cover: central banking. Here’s how the economy could be weaponized in order to bring down a second Trump government — and how to stop it.

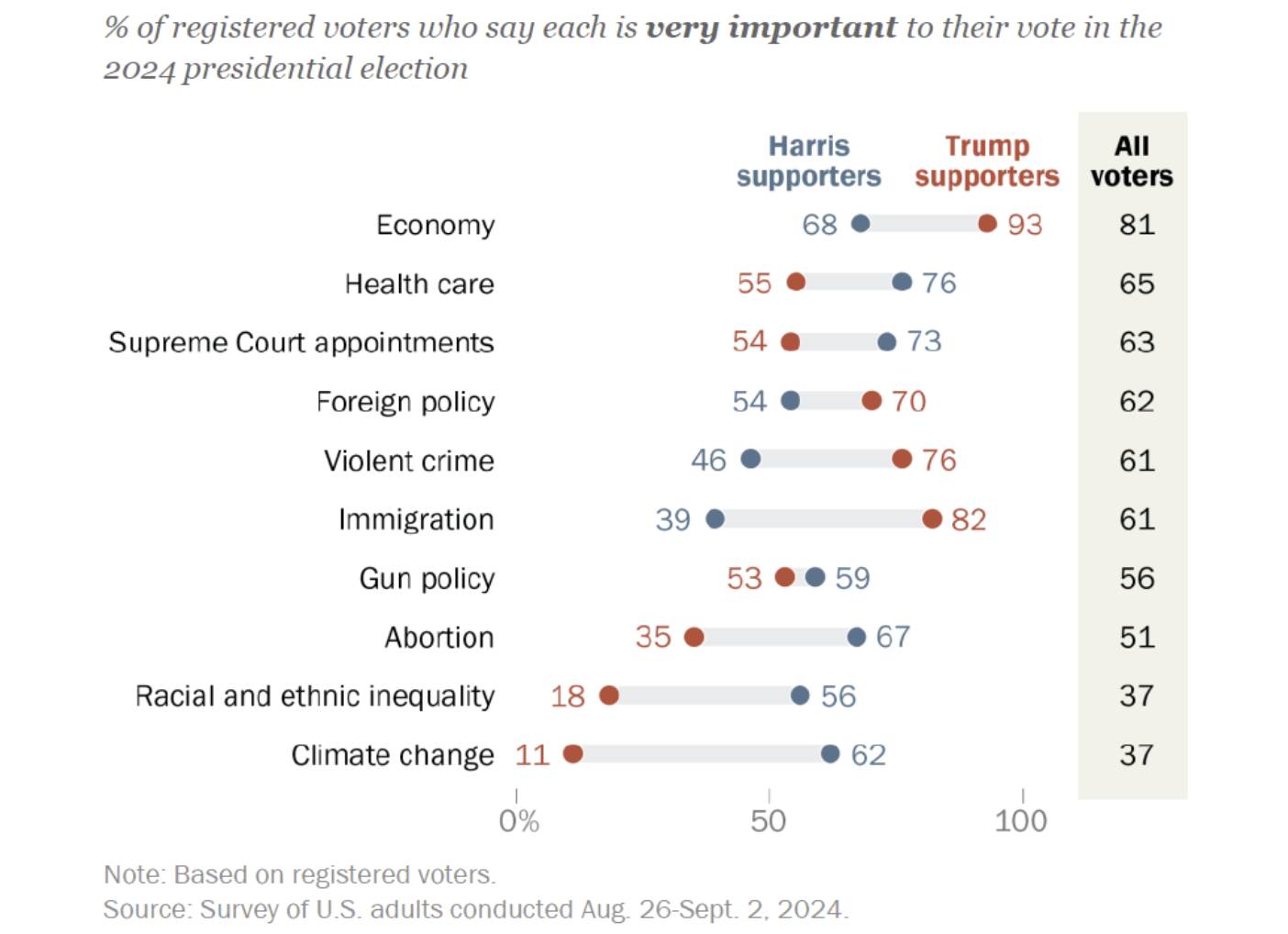

The economy is the most important issue for voters this election. 90% of respondents to Gallup polling said the economy was either an “extremely” or “very” important factor affecting whether they vote for Trump or Harris. 80% of all voters, including 93% of Trump supporters, and 68% of Harris supporters, told Pew Research that the economy was their leading issue. Weekly YouGov polling shows twice as many voters since mid-2021 think the economy is getting worse as those who think it’s getting better.

But all of Trump’s plans to revive American manufacturing, invest in the armed forces, and build ten new “Freedom” cities, rely on having enough tax revenue, deficit headroom, and dollar stability to do so. This requires stable management of the monetary supply by the Federal Reserve, and enough confidence by the markets to allow the government to borrow necessary funds. Both are in question. Since the COVID pandemic, the Federal Reserve has increased its assets by 80% since early 2020 via quantitative easing (a.k.a. digital money-printing). If the growth of the money supply outpaces goods production, this causes inflation.

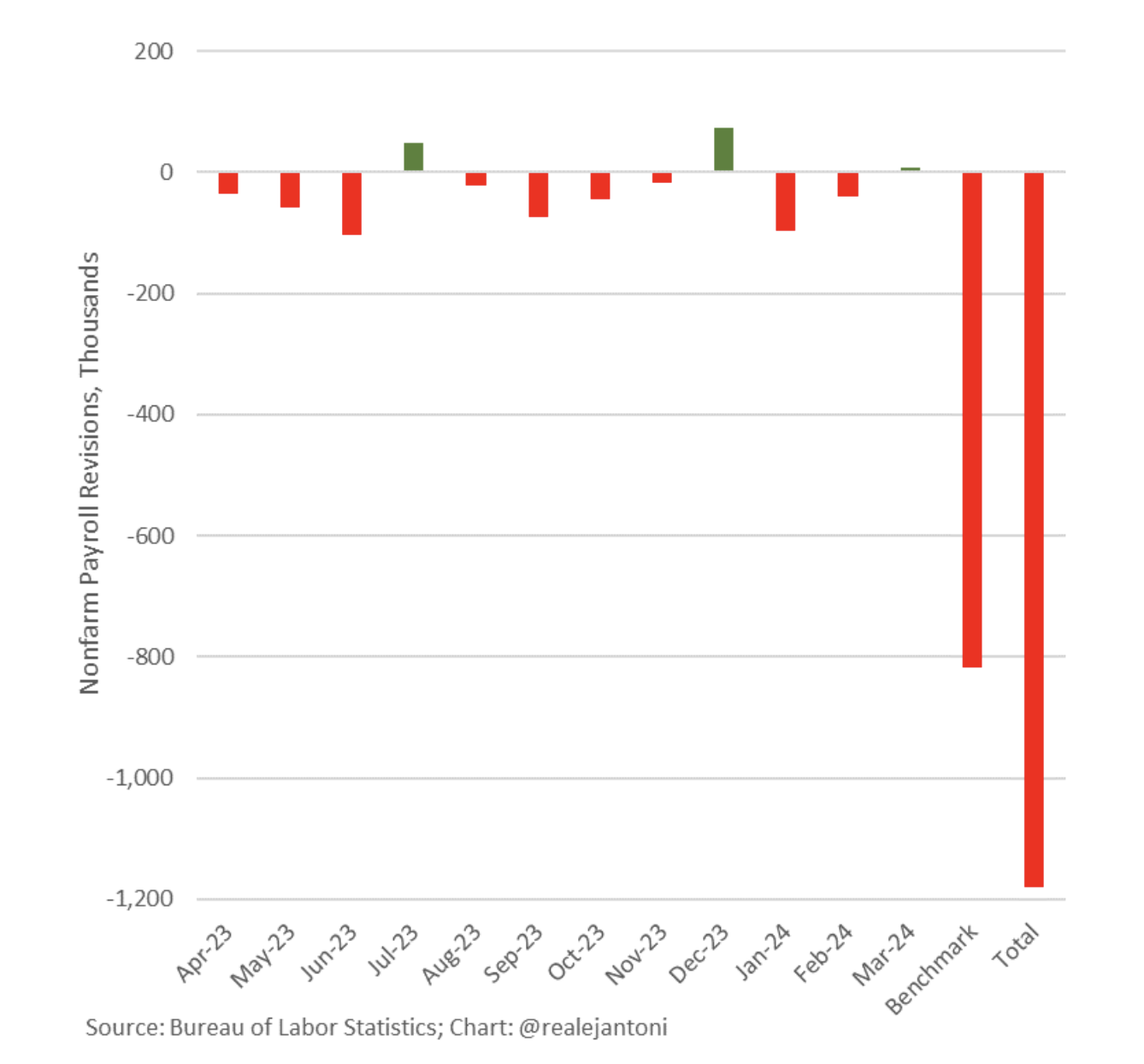

Per modern monetary theory, the banks believe it is their responsibility to control inflation and unemployment. They’re failing at the latter: with the Biden/Harris administration’s annual jobs figures revised down by almost 30% (-818,000). If all prior overestimates are added up, it totals 1.2 million jobs that the Biden/Harris administration said they had created, and haven’t.

Gas prices are up 40% since 2021; bread, 39%; and average real-terms weekly wages down 3.9%. Biden/Harris’ $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (2021) caused grocery prices to increase 13.5% by August 2022. However, because the employment figures are down, the Federal Reserve can now justify recalibrating interest rates to conduct quantitative tightening and reduce inflation. The Federal funds rate has decreased from a 23-year high of 5.5% to 4.81 — conveniently timed to ensure Harris’ campaign is less tainted by Biden’s economic record. Prior to COVID, during the Trump presidency, it had reached 0%. But while they are coming down, it is important to remember that a sudden spike by a Federal Reserve acting autonomously of the wishes of the elected government could cause market volatility that can bring economic plans to a screeching halt.

It is feasible that Trump could get less preferential treatment from the Federal Reserve than Biden and Harris. In a recent interview, Patrick Bet David brought Trump’s attention to the fact that the Federal Reserve had maintained near-zero% interest rates during the Obama and Biden/Harris administrations. Interest rates began to climb in January 2017, after Trump’s inauguration. This was despite an average GDP growth of 2.5%, and real wage growth of 2.1%, outpacing inflation throughout the Trump economy. The difference between Trump and Biden/Harris is clearest in projections that Trump’s economy will cause “deflation” — a reduction in goods prices for American consumers. However, Harris-friendly press suggest that “The Fed would be terrified” that a “deflationary spiral” could risk a recession, and necessitate Federal Reserve intervention to adjust interest rates. Sixteen Nobel Prize-winning economists signed a letter in June, condemning Trump’s “fiscally irresponsible budgets” and saying he would “reignite’’ inflation. These same economists were not as vocal during Biden/Harris’ first two years in office, when inflation exceeded 9%.

President Trump was warned about the effect of interest rates on his tariff plans in a combative interview with Bloomberg News editor-in-chief John Micklethwait.

At the moment, there is a thing called the Trump trade in the markets. Do you know what that is? The Trump trade is very simple. People are betting that your policies are going to drive up debt, they’re going to drive up inflation, so they’re going to drive up inflation rate — interest rates. Are the investors wrong? […]

The markets are looking at the facts. You are making all these promises. The latest one was car loans. You’re flooding the thing with giveaways. […]

I was actually quite kind to you. I used $7 trillion. The upper estimate was $15 trillion. People like the Wall Street Journal, who’s hardly a communist organization. They have criticized you on this as well. You are running up enormous debt.

In anticipation of another Trump presidency, media and economic forecasters are inducing uncertainty in markets about Trump’s economic policies. Despite the Biden/Harris administration adding over $1.4 billion more to the deficit than Trump, market analysts are warning Trump’s “zany promises would blow up the deficit”. According to The Economist, market volatility has risen to the highest level this year. In the last six weeks, ten-year Treasury yields have increased from 3.6% on September 16th, the lowest in almost a year and a half, to 4.2%. This could discourage investors in the first year of Trump’s second term, limiting GDP growth compared to inflation. This would be a pretext to the Federal Reserve stepping in with increases in interest rates, putting a stop to Trump’s tariffs, and scuppering his popular proposal to abolish income tax.

Vice Presidential nominee JD Vance is vigilant for this possibility. In an interview with Tucker Carlson, Vance said,

But if Trump wins, it’s not just going to be smooth sailing for four years. They’re going to do everything that they can to take down this President. I think it’s probably the most and the most important in the most impactful way they could try to take down his presidency: [it] is by spiking the interest rates.

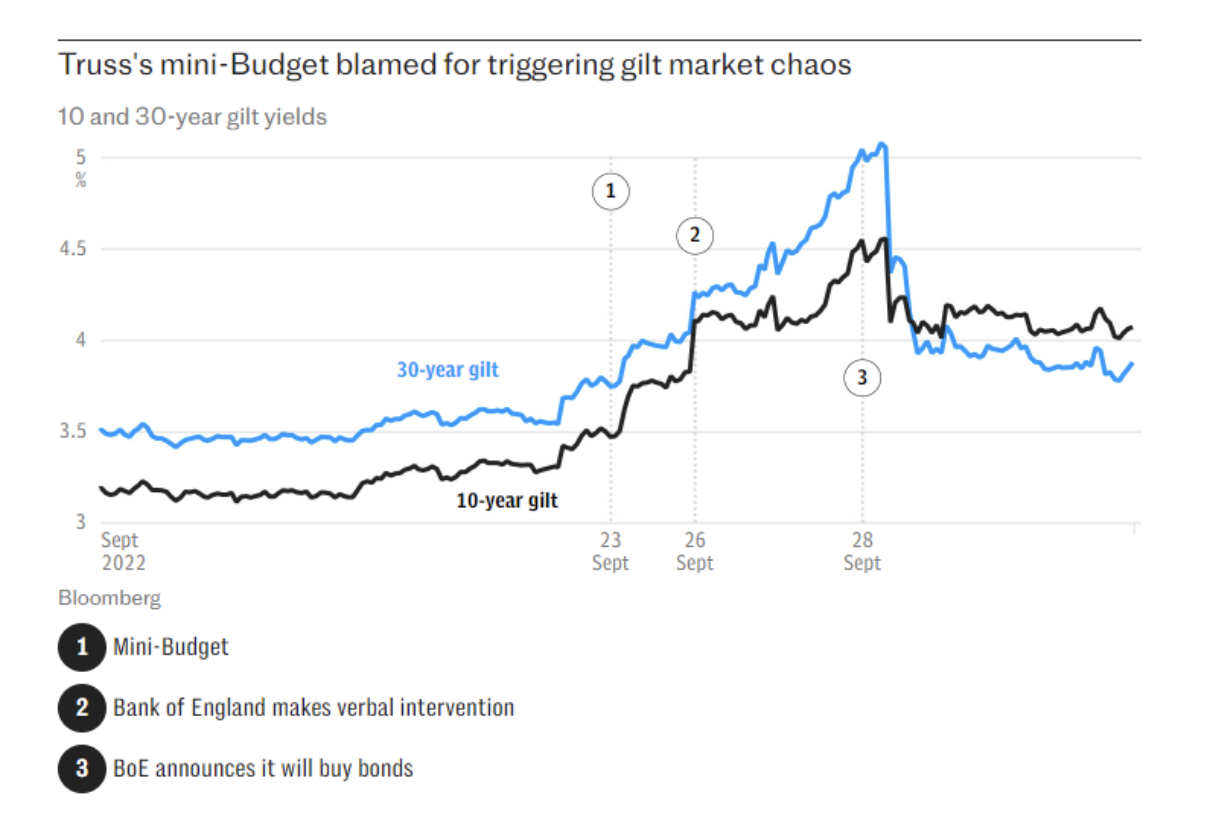

You saw this, by the way, Tucker, [with] Liz Truss in Britain, ok — Which, by the way, like I like Liz Truss, I disagree with her on a lot of issues, so I’m not I’m not trying to stand up or say Liz Truss is my person. But look, she came in, she had a plan and the Bank of England, I think, made a lot of mistakes — maybe intentional. Interest rates shot through the roof and it took down her government in a matter of days. Of course, we don’t have the same style of government, but it would be devastating to the President if you had this bond market death spiral. And that’s one of the things we’re going to have to fight against when we win.

In Britain, the shortest-serving Prime Minister’s name has become synonymous with failure in government. Conventional wisdom holds that Liz Truss’ “disastrous” mini-budget crashed the economy, necessitated the central banks intervene with an increase in interest rates and “a £65bn support scheme”, and ruined many a Christmas with unaffordable mortgages. After forty-four days of turmoil, Truss resigned outside Downing Street, infamously outlasted by a Tesco lettuce. Anywhere she goes, Truss is hounded by hostile press, and has her speeches sabotaged by self-styled “accountability project” comedians who are conspicuously unbothered with holding the party presently in power to account. For merely speaking to me, Truss and I became headline news for a week during the general election campaign — with MPs, newspapers, and broadcasters asking the Prime Minister and Chancellor if it was prudent for Truss to appear on my podcast. Many made defamatory statements after failing to do sufficient research before speaking.

But this continued preoccupation with Truss as a bipartisan hate figure begins to look like a frustration with the fact that she refuses to be scapegoated. Truss has remained resolute that her short-lived tax-cut proposals were not to blame for Britain’s financial crisis in September 2022. Just as with many accusations made about Donald Trump: all is not as it first appears. The evidence is mounting, out of the mouths of the banks themselves, that fault lies with financial regulators, not the former Prime Minister, for crashing the economy.

Truss has urged Vance and Trump to look to her government as a cautionary tale, to avoid having their next term thwarted. Therefore, it’s worth detailing exactly how Liz Truss’ government was brought down.

When I interviewed Liz Truss last May, and asked for evidence of a bankers’ coup, she made the following four claims:

- The night before the mini-budget, the Bank of England sold £40 billion of GILTS (government bonds), without informing her or the Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng.

- The Bank of England also raised interest rates, with a short-term resolution deadline.

- The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) leaked an inaccurate forecast of a £70 billion shortcoming in public finances, again without informing either the Prime Minister or Chancellor.

- Throughout the controversy, Conservative party MPs and civil servants were leaking briefings to the media, violating their duties of confidentiality and due impartiality.

Let’s examine if there is any truth to these claims.

The ill-fated mini-budget was announced on Friday 23rd September 2022. According to then-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s Growth Plan, it aimed to achieve a 2.5% annual GDP growth rate. For comparison: in August 2024, the GDP growth rate was estimated to be 0.2% since May. Debt is now 100% of GDP — increasing 4% in a year, to levels not seen since the 1960s. On the second anniversary of the mini-budget, Truss claimed that her policies would have broken the “economic doom-loop” created by the highest tax burden since 1948, a sub-replacement birth rate, and annual population increases driven solely by net-cost record migration. Had Truss paired fiscal restraint with restrictionist policies on low-wage immigration, Britain may be in a better place now. However, there are reasons to believe she would not have achieved that feat even had she remained in Downing Street — which I will cover later.

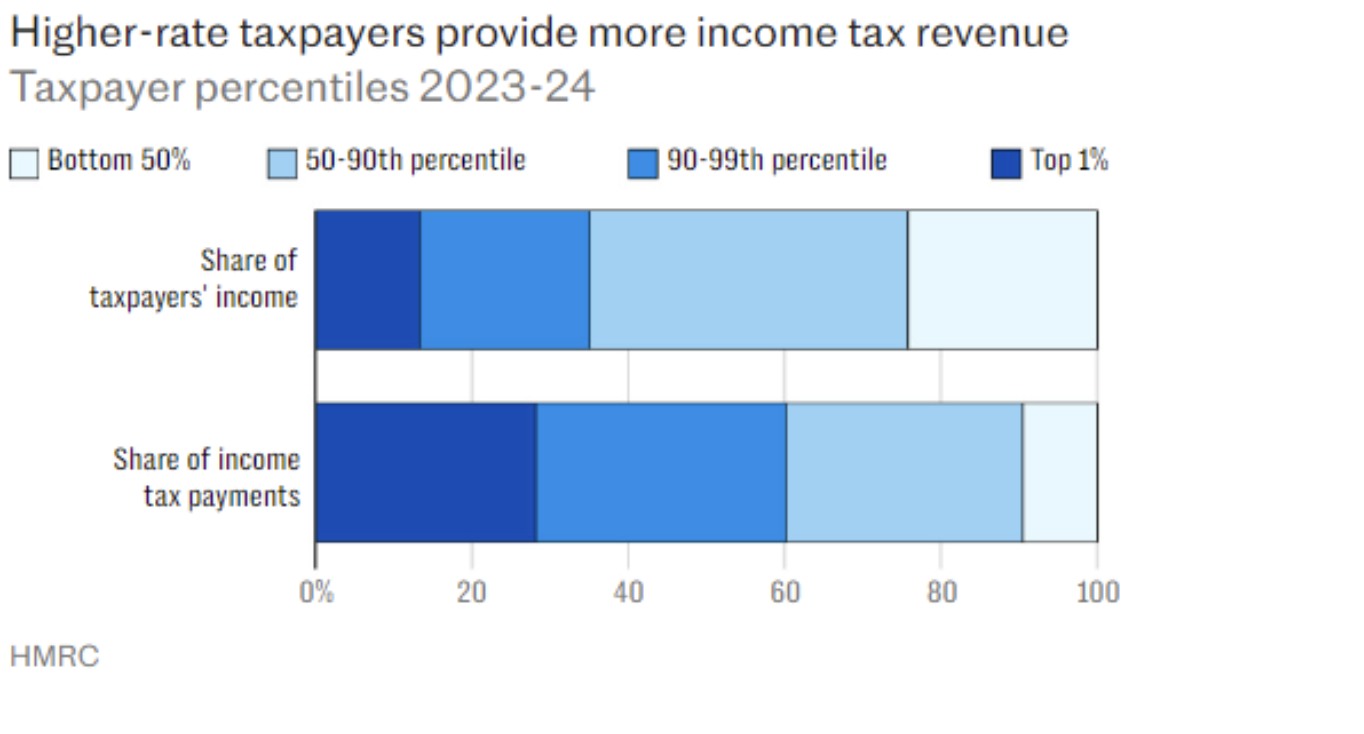

The case against Truss is that she committed to £45 billion of “unfunded tax cuts” alongside an increase in spending, paid for by increasing Britain’s short-term debt. But the mini-budget only promised to cut the basic rate of income tax by 1%, and abolish the additional 45% (45p) rate charged on taxable income over £150,000; which, before the budget, Truss claims that forecasters had told her raised nothing. Now that Labour are seeking to extort more from this income bracket, Chancellor Rachel Reeves has been warned that they contribute more than two fifths of all annual income tax to the Treasury. The UK is now set to lose the most millionaires in the world to emigration by 2028 — meaning the Treasury will have even fewer of these high-earners on which to rely. Nonetheless, this policy became the first to be reversed after a media storm on October 3rd, during the Conservative Party Conference.

The other “unfunded tax cuts” were merely a refusal to raise taxes as the previous Chancellor, and her successor, Rishi Sunak had planned. The mini-budget would have reversed a planned 1.25% increase in National Insurance rates — a second tax on income which is supposed to fund socialized healthcare and state pensions, but which falls short of escalating costs for Britain’s ageing population. It would also have frozen corporation tax at 19%, rather than the planned rise to 25%. This proved controversial, after Rishi Sunak and Janet Yellen negotiated a global minimum corporation tax rate of 15%. It was the second policy to be scrapped, on October 14th — the same day that Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng was sacked and replaced with Jeremy Hunt.

Additional policies included:

- Reversing the 1.25%-points increase to dividend tax rates.

- Freezing the bank surcharge, preventing its planned fall from 8% to 3% in April 2023.

- Increasing the stamp duty (house-buying tax) threshold from £250,000, from £125,000.

- Permanently setting the capital tax allowance (tax-exemption for investments in plant and machinery) to £1 million — preventing the planned fall to £250,000 in April 2023.

- Introducing VAT-free shopping for non-UK visitors.

- Repealing IR35 reforms to off-payroll working from April 2023 — saving small businesses money.

- Scrapping the cap on bankers’ bonuses.

The UK’s Debt Management Office was asked to borrow £72 billion more from markets in 2022/23 than was requested in March 2022. This was, in part, to deal with the inherited mess of the Energy Price Cap, passed by the Theresa May government. Britain’s energy regulator Ofgem sets a three-month price control for household energy bills. Successive governments had sabotaged Britain’s energy generation capacity — including banning fracking under Boris Johnson. Britain then embarked on a Net Zero policy of investing in renewables which has been modelled by the National Grid to cost £3 trillion, and fail to meet consumer demand by >74%. The cap was set to expire just as global gas prices spiked, due to the war in Ukraine. Truss proposed spending £150 billion on the Energy Price Guarantee to freeze household bills at £2,500 for two years. This measure remained, despite being the most expensive commitment in the mini-budget.

Truss had hoped to bring energy bills down in the two years before the Guarantee expired, by reissuing fracking licenses. Making use of North Sea reserves would provide Britain with an affordable, less-emissions-intensive alternative to oil and gas imports. Combined with the Biden administration’s day-one cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline, banning fracking on federal land, and sales of strategic reserves to China’s Sinopec, the UK and US have allowed Russia to become the leading exporter of oil and gas to Europe. Reversing this self-sabotage would have lowered Britain’s energy prices — the highest in the world — and put NATO in better standing against Russia. However, when thirty-one Conservative MPs abstained from a vote to do so in Parliament, it acted as a de facto no-confidence vote in Truss’ government. She resigned the following day.

All of these measures were blamed for £30 billion of the £60-70 billion “fiscal hole” forecast by the OBR after the mini-budget. The remaining half was attributed to higher anticipated costs of servicing government debt and meeting spending commitments for welfare and state pensions. This forecast was leaked to The Guardian before it was provided to either the Chancellor or Truss. The report detailed that the Treasury was “closely guarding the details of the OBR forecast, despite pressure from rebellious backbench Conservative MPs demanding an early release”. Both Truss and Kwarteng deny that this was in their possession prior to the mini-budget. Nobody knows who leaked the forecast to the press. No investigation has been conducted. The forecast has since been found to be false — revised months later to be an unexpected £30 billion surplus. Self-assessment tax receipts in January 2023 were higher than expected, meaning the OBR’s modelling was wrong by a factor of £130 billion.

For those asking: why didn’t they reduce spending? The Truss government had planned to release a follow-up plan, detailing where costs would be cut across government — but they didn’t have time to do so. Moreover, as one government source explained to me, the annual forecasting cycle of the OBR prohibits cost-cutting which takes longer than a year from being accounted for. This includes any cuts to spending commitments made by an act of Parliament, such as on foreign aid, immigration and asylum, or climate change; and any cuts to government departments, given civil servants receive a year of severance pay when made redundant. The purpose of the state seems to be to constantly expand itself. Any reductions in its remit or revenue are unthinkable. This is as much for personal as for ideological reasons, as Truss detailed in her political autobiography Ten Years to Save the West:

Because of the UK’s poor financial position, we had reduced our spending on aid as a proportion of GDP to 0.5 per cent from 0.7 per cent (as it happens, I am not in favour of these input targets anyway). But unbelievably, we hadn’t reduced funding to the World Bank. The UK was its third-biggest donor but the Treasury was very resistant to reducing funding. I had a row with Rishi Sunak to get the World Bank contribution to be reduced as much as possible, which I eventually won. The problem is that too many former Treasury officials and ministers go on to work for the World Bank and similar institutions, so they do not want to see it deprived of funds. It’s yet another body that does not serve a key purpose.

So, OBR and Treasury officials may have been inclined to brief against her, leaking the damaging forecast, to protect their own job security.

Another way of reducing economic costs could have been to reduce immigration. A new OBR report has admitted that low-wage immigrants — earning half the average UK salary — comprise 54% of worker visas every year. Over 70% of migrants on worker visas are net tax recipients. Each migrant costs the taxpayer £465,000 by the time they reach 81 — the average age of death in the UK. This presumes they enter the country aged 25. However, we know from data from Denmark that second-generation migrants repeat the economic patterns of their parents. This means that, after the costs of healthcare and schooling, these migrants are never net-tax contributors, from birth to death. Given that 74% of all jobs in the UK since 2011 went to migrant workers, we know the costs of this policy will well exceed the £70 billion “fiscal hole”. The OBR itself has overstated the economic output of migrants arriving every year by £8.36 billion since 2019. It modelled migrants’ economic output at £182.8 billion between 2019 – 2023; but the Centre for Migration control found the output is actually £174.6 billion. How can accurate budgets be made with such expensive errors?

So why didn’t Truss stop mass immigration? I asked her this in our interview, and Truss said that the OBR had threatened to publish damaging financial modelling if she both cut taxes and raised immigration, which would prevent the government from borrowing to pay for the Energy Price Guarantee. Then-Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s attempts to meet manifesto commitments and reduce net migration were cost by the OBR at £6 billion; whereas liberalizing work visas were forecast to raise £14 billion in revenue. We now know both of these figures were wrong, but Truss pleaded ignorance at the time. In hindsight, she would have stuck to her guns. But it was too late: both Braverman and Truss were sacked, and the UK saw annual record net migration in 2022 – 2023.

One should note, though, that none of Truss’ policies affected interest rates. How could they? The Bank of England was given complete autonomy from the Treasury to set interest rates and control the M1 money supply by Gordon Brown in 1997. Interest rates increased two days prior, and were announced the night before the mini-budget — by 0.5 percentage points to 2.25%, to the highest level since the 2008 financial crash. They were raised completely independent of Truss’ mini-budget. The Bank had also disappointed speculators, who had anticipated a greater increase — causing confidence to fall in UK markets. The Pound fell to its lowest ever level against the US Dollar, and by 2.2% against the Euro; and the FTSE 100 declined by 2.2%.

This coincided with a 23% drop in the price of thirty-year GILTs (government bonds), stemming from long-term failures to limit leverage in UK pension funds. This was caused by liability-driven investments (LDIs): the product which the Bank of England purchased to use borrowed money to buy GILTs. The Bank had used LDIs to conduct a “‘borrowing short” and “lending long” strategy for pension funds. This same high-risk strategy was the cause of the 2008 financial crash. As John Moynihan explains, GILTs were purchased at the start of the year with the expectation that inflation would remain low, allowing them to make a profit on long-term sales; but, as the Bank of England continued to increase interest rates, it became clear that they would make a loss on the GILTs. When GILT prices fall, borrowing costs rise, and fiscal headroom for the government decreases. Deputy Governor Sarah Breeden admitted in November 2022 that this crisis had been caused by “poorly managed leverage”.

Truss entered Downing Street when ten-year GILT yields had reached 2.94% — up 194 basis points from the start of 2022. This translated to a 10% loss of value. This continued to rise 130 basis points within days of the mini-budget. The Bank of England must have known about this, because it reduced its own pension fund’s participation from 100% to 82% in the Blackrock-leveraged LDI fund. The Bank of England sold £70 bn in GILTs to raise funds to meet margin calls. That £70 billion figure is the same as the leaked forecast by the OBR, but they aren’t the same “fiscal hole”. The Bank of England sold GILTs to save its mismanaged balance sheet; whereas the OBR figure concerned a fictitious gap between revenue and spending. It then bought £65 billion worth of GILTs in its intervention to stabilize the market reaction to its sales and rise in interest rates.

This all happened independently and before Truss’ mini-budget. Hence why Bank of England reports have since admitted that their interventions in the bond markets were responsible for at least half, if not two-thirds of the crisis. Five analysts concluded the Bank of England was “not particularly sophisticated at managing their liquidity risk”, and that 0.66pc of the 1.03pc jump in 30-year borrowing costs was caused by trading decisions made “well in advance of the onset of the crisis and before the election of Liz Truss as prime minister”.

An earlier post on the Bank of England’s blog had admitted that, while the mini-budget sparked the sale of GILTs, “LDI selling accounted for at least half of the fall in GILT prices during the crisis, with fiscal policy likely accounting for the remainder.” So, Truss is being exculpated of blame in real-time, by the architects of her demise. Even more mysterious is the fact that, after new Labour Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ budget announced £40 billion in tax rises, taking Britain to its highest tax burden in history on 30th October, GILT prices increased to a 4.56% yield — 0.3% higher than after Truss’ mini-budget. Curious, then, that Reeves has faced no calls to resign from the press, her own party, or the financial establishment.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

A report for the government’s Treasury Committee this year condemned the Bank of England’s monetary policy, too: saying their unique sale of GILTs alongside quantitative tightening (raising interest rates) “constitutes a leap in the dark”. The report estimated that a potential £50 – £130 billion has been lost by the Bank’s monetary policies — double that of the “fiscal hole” leaked by the OBR. Despite this, the report said, “We did not receive substantial evidence that QT had been a causal factor in the outbreak of the LDI crisis”. What should arouse further suspicions is that the Bank of England reported a profit of £3.5 billion from its bond market intervention when the final sale completed on the 19th January 2023. This 18% return is £46.5 billion less than the lower estimate of what the Bank was later found to have lost. Yet, Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey has not lost his job for mismanaging public funds.

Nor were any Conservative MPs or civil servants punished for leaking briefings or undermining public trust in Truss’ government. Unlicensed biographers Harry Cole and James Heale report that, on 16th October, “as Hunt planned his speech to announce the U-turn the following day, the first Tory MPs went public with calls for Truss to go: Crispin Blunt, Andrew Bridgen and Jamie Wallis.” Both Blunt and Wallis became embroiled in sex scandals: with Wallis found guilty of abandoning a car he crashed while crossdressing, and Blunt detained by police under investigation for rape. Blunt had previously apologized after defending convicted sex offender, former MP Imran Ahmad Khan. Both MPs were allowed to serve their term in Parliament and stand down at the next election — rather than suspended and expelled from the party.

Truss attributes her resignation being made inevitable to both the Conservative Parliamentary party, and senior civil servant Simon Case. By Monday 26th September, Truss had protested to the Conservatives’ 1922 Committee that the pound had returned to its pre-mini-Budget level, and the UK still had the second-lowest debt ratio in the G7. Neither fact spared her from pressure within her party to resign. Then came a letter from Cabinet Secretary Simon Case, urging Truss to abandon the tax cuts announced in the mini-budget. This was first reported by The Spectator: which, as I covered previously, had long-standing personal and professional ties to her leadership rival, Rishi Sunak. The letter confused Truss, as Case was present at Chevening when the Growth Plan was being written — meaning he knew all of its policies ahead of time, and raised no concerns.

Former Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries cites a source in her book, The Plot, who states that former Downing Street advisor Dominic Cummings and Cabinet mainstay Michael Gove insisted the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Mark Sedwill, was replaced by Simon Case on 9th September 2020. Cummings famously hated Truss, nicknaming her “the human hand-grenade” when they worked together under Gove at the Department for Education – a claim also first printed in The Spectator by Rishi Sunak’s best man, James Forsyth. Heale & Cole note, in Out of the Blue, that when Truss selected her Cabinet, “figures such as Michael Gove, Grant Shapps and Sajid Javid had been culled: a decision that would come back to haunt Truss within weeks.” This led, as another source told Dorries, to Gove “cruising around the Conservative Party Conference attacking Liz Truss to any journalist with a camera who would listen, telling journalists [that] he and Grant Shapps would have her out by Christmas.”

After July’s Kings’ Speech, civil servants breached their due impartiality clause by editorializing, in the briefing notes, that Truss’ government was “a lesson in how not to do fiscal policy”, and that measures to give more power to the OBR were necessary to “ensure that the mistakes of Liz Truss’s ‘mini-budget’ cannot be repeated”. Truss wrote a letter to Case, asking this “political attack” be removed, and that a “suitable admonishment” be given to the civil servants responsible. The references to Truss were removed, but she received no explanation or apology from Case. I wouldn’t expect one to come: as Case has now resigned, due to a neurological condition. However, his removal may be expedited after arguments with long-time Gove ally Sue Gray, over his inability to prevent the press from reporting damaging stories about Keir Starmer’s clothing donations from Labour Lord Alli. It appears leaks only matter when they make the government that the civil service prefers look bad.

Case himself had been appointed head of the Partygate inquiry, which brought down Boris Johnson, and allowed Truss to briefly become Prime Minister. However, Case had to recuse himself after it emerged an event was held in his own office. This allowed Sue Gray to take supervision of the investigation; before going on to become Keir Starmer’s chief of staff, and provide her son with a safe seat to become a Labour MP.

On 22nd October 2022, Truss resigned. She has since been scapegoated for reckless monetary policy by the Bank of England and inadequate modelling by the OBR. Disreputable characters in her party and the ostensibly neutral civil service collaborated to oust her. None of the villains in this story were held to account. The only positive was that this ordeal taught Truss the following valuable insight:

This, I think, is the key to understanding why I was ultimately unable to deliver on my mandate and why my premiership ended the way it did. I came to realize there is no such thing as ‘the market’ in this sense. Rather, there are groups of influential individuals in the financial establishment, all of whom know and speak to one an-other in a closed feedback loop. The Treasury, the Bank of England, and the OBR are deeply embedded in these social and professional networks and share the same belief in the established economic orthodoxy. It is a classic example of groupthink. Over time, this group has moved to the left, adopting net zero goals and diversity targets while arguably neglecting many of their core duties, such as the Bank of England’s responsibility to keep down inflation and maintain financial stability.

Truss’ fall is a cautionary tale. Tasking ideologically captured institutions with carrying out the will of an insurgent government is a recipe for disaster. Staff must be changed, and bureaucracies brought under the control of elected governments, before any policies can be implemented. Otherwise, the next Trump administration will once again spend so much time fighting enemies in the “Deep State” that it will fail to deliver for the American people.

Furthermore, Trump’s team should be watchful of actions by the Federal Reserve to recover from long-term consequences of economic mismanagement by the Biden/Harris administration. Like Truss, Trump would be inheriting a mess from his predecessors. The Keynesians in the Fed will recoil at any cuts to regulations, believing the role of the state is to manage the economy. International bodies like the World Bank and IMF are keen subscribers to woke orthodoxy on gender inequality, climate change, and immigration. Any dissent will be considered a declaration of war on their moral consensus. They will draw up the drawbridge to the prospect of America further borrowing its way out of a brewing deficit crisis. Just as in the UK, Blackrock manages 35 million Americans’ pension funds. CEO Larry Fink won’t take kindly to legislation targeting his ESG Scores — which multiple Republican states have already passed. It would be all too easy to blame the fallout from Biden/Harris on a potential second Trump term.

If Trump plans to declare war on the financial establishment and other unelected agencies, then they had best concoct a plan to prevent interest rates, pension funds, and financial forecasts being used against them. Furthermore, Trump must make prudent staffing choices, to ensure nobody within his administration has an incentive to leak to the press and undermine confidence in his agenda. Otherwise, his promise to Make America Great Again will be as short lived as Truss’ tenure in Downing Street.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.