On November 12, Justin Welby announced his resignation as Archbishop of Canterbury following an independent report by Kevin Makin into serial child abuser John Smyth. Commissioned in October 2019 and published in November 2024 – with haste following a leak – the long-awaited Makin Report (also known as the John Smyth Review) investigated the Church of England’s mishandling of the scandal.

The British barrister John Smyth, who died in Cape Town in 2018, was accused of abusing more than 100 boys and young men. He is believed to have assaulted boys he met at Christian summer camps he helped run in Dorset over the 1970s and 1980s. These camps were funded by the Iwerne Trust, of which Smyth was chairman between 1974 and 1981. A victim in the report described them as “activity-based holidays for public school boys who were accepted from a list of 30 elite boarding schools […] all of which had their own Christian Forum/Union organisation, run by staff member(s) at the individual schools”.

Smyth identified pupils associated with the Iwerne camps, in particular a Christian group at Winchester College, and took the boys to his home near Winchester where he carried out violent lashings with a cane in his purpose-built, soundproofed shed. The report says that eight of the identified boys received a total of 14,000 lashes, while two more received 8,000 strokes between them over three years. The beatings were “prolific, brutal and horrific”.

The Makin Report found that the Church covered up “abhorrent” abuse. Despite the fact that his actions were identified as early as 1982, the report concludes that Smyth was never exposed and he was therefore able to continue his abuse. The Iwerne Trust carried out a secret investigation but did not inform the police. Likewise, Winchester College banned Smyth from its premises but failed to report the crimes to the police, who were only made aware of the case in 2013. In the meantime, Smyth moved to Zimbabwe in 1984 and continued to run summer camps for children. Predictably, he abused boys and even faced charges of killing a 16-year-old boy at a holiday camp in 1992. Then, after relocating to Cape Town in 2001, he was removed as leader of his local church after accusations of inappropriate behaviour. He died before he could be questioned by the police, arrested, or tried.

The report is explicit about the role of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was a colleague of Smyth’s at the camp over many years and did not act when the truth came to light in 2013. He “could and should” have reported the abuse to police at that point. The BBC outlines the timeline of events here.

Having initially claimed that he would not quit in the interests of the Church, Welby stepped down amid mounting pressure. In a statement released on his official website on 12 November, he wrote that “The Makin Review has exposed the long-maintained conspiracy of silence about the heinous abuses of John Smyth”. He believes that “stepping aside is in the best interests of the Church of England”.

It is very clear that I must take personal and institutional responsibility for the long and retraumatising period between 2013 and 2024 […] I hope this decision makes clear how seriously the Church of England understands the need for change and our profound commitment to creating a safer church.

The buck does not stop with Welby, however. The Church Times reports:

Mr Makin writes that Smyth’s abuse was known “at the highest level” of the Church of England from July 2013, by, among others, Archbishop Welby and the Rt Revd Stephen Conway, then Bishop of Ely, together with other senior church officers. There was, however, “a distinct lack of curiosity shown”, Mr Makin says, concluding that Smyth “could and should have been reported to the police in 2013”.

The Telegraph reveals that at least thirty members of the clergy face being sacked over their failure to stop the most prolific child abuser in the institution’s history. One minister has stepped down already. The Church’s safeguarding team is currently examining the officials mentioned in the Makin Review as having prior knowledge of allegations against John Smyth. Time will tell the extent of the repercussions of this scandal. As Isabel Hardman asserts, “resignations alone won’t fix the Church of England”. There needs to be radical structural reform.

It is a grave omission that Hampshire Police only opened an investigation in 2017 after Channel 4 broadcast a report into this prominent evangelical. They knew about it in 2013. The 2017 exposé came after the 1982 report by the Iwerne Trust was finally made publicly available in 2016. At the time a statement was released on behalf of the CoE:

We recognise that many institutions fail catastrophically, but the Church is meant to hold itself to a far, far higher standard and we have failed terribly. For that the Archbishop apologises unequivocally and unreservedly to all survivors.

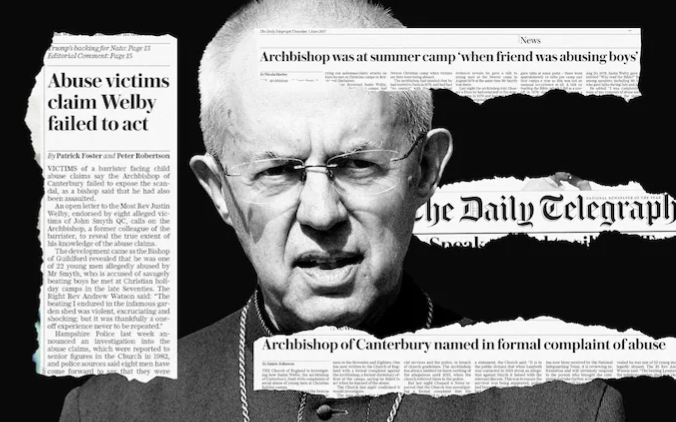

In a series of subsequent reports, The Telegraph shed further light on the abuse and explored Justin Welby’s connection to the scandal. Alex Barton outlines these reports here.

Credit: The Telegraph

Ysenda Maxtone Graham has pointed out some peculiar happenings elsewhere in the Anglican Church. In a Spectator article titled “What’s gone wrong at Winchester Cathedral?”, she addresses concerns around the Dean and the controversial Precentor Andrew Trenier:

The Dean of Winchester, the Very Revd Catherine Ogle, has announced that she will be retiring on 1 May 2025. The timing is interesting, as news of Ogle’s retirement emerged just hours before the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby resigned over the John Smyth abuse scandal.

Interesting timing indeed. Moreover, Revd Ogle announced her retirement against the backdrop of drama in the Cathedral, reported on in The Hampshire Chronicle and The Living Church. The esteemed Musical Director Dr Andrew Lumsden resigned his post of 22 years for apparently no reason in May – when asked about his reasons for early retirement mid-term, he replied, “I can’t say”. Has he signed an NDA, Maxtone Graham wonders? Before this, the talented assistant organist George Castle was singled out for redundancy out of 115 staff. Castle told The Spectator of the “systematic failure of the management of the organisation to consider their pastoral and welfare responsibilities towards employees”. He appealed, and Jean Ritchie KC concluded that “the Precentor did behave inappropriately to the appellant on occasions in 2020” and that “the appellant witnessed inappropriate behaviour to other members of the [music department]”. Is this simply a coincidence? Perhaps – if so, it adds to the argument that the CoE needs to revise its safeguarding measures and ensure more transparency.

It seems that something is rotten in the state of Denmark. More revelations are bound to surface before long. Other victims of John Smyth might come forward thanks to the report, and surely further investigation into the camps in Zimbabwe is needed. In a statement of 7 November issued by Andrew Graystone, a number of victims and survivors of John Smyth demand clarity: “The C of E needs to commit today to produce a follow-up report in 18 months time [sic] based on […] future evidence, should that be necessary.”

***

So who will succeed Welby as the 106th Archbishop of Canterbury? The Bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury is the most senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, as well as the ceremonial head of the Anglican Communion. He or she holds a seat in the UK House of Lords alongside secular legislators, at the same time as overseeing Anglican churches in more than 160 countries. The archbishop also manages the day-to-day business of the Church of England. Further information about the role can be found here. It requires spiritual leadership, moral authority, and an unwavering Protestant vision. But the process by which the archbishop is appointed is opaque and, because of the origins of the Anglican Church in Henry VIII’s quarrel with the Pope, secular as well as religious institutions play a part in it. The Crown Nominations Commission (CNC) sends its recommendations to the Prime Minister (currently an avowed atheist), who will then pass them on to the King. The King, as successor to Henry VIII, has the final word.

The Guardian reports with predictable gusto:

There will be many who think it is time for a woman to lead the C of E. Since Welby forced through the appointment of female bishops early in his tenure, more than two dozen have been appointed, and several are thought to be in the frame to succeed him. Equality campaigners say the appointment of another white man will reinforce the impression that the C of E is unrepresentative of the UK’s diversity.

Apparently “many in the church and beyond will be hoping that the successful candidate is a woman “or person of colour – or both”.

One might ask why there is so little talk about the essential requirements for a Christian leader including a life dedicated to God; intimate knowledge of the scriptures; and the capacity to deliver powerful messages of unity to the country in difficult times. Some will see it as absurd that DEI mantras have infiltrated the Church of England to the extent that faith is put on the backburner.

The article continues to hypothesize about the viable candidates, like a bizarre liturgical Tinder. Every single entry talks about a hot political topic or introduces identity politics, which is unfortunate given the abuse attendant on the calls for Welby’s resignation. Stephen Cottrell, Archbishop of York, is just about acceptable because he’s “an Essex boy who was educated at a secondary modern and later a polytechnic”. Guli Francis-Dehqani, Bishop of Chelmsford, is Iranian and “broadly in favour of LGBT+ inclusivity”. Martyn Snow, Bishop of Leicester – the tone warms up here – is “the lead bishop for issues of sexuality within the church […] he has spoken out on issues of racial justice, including ‘taking the knee’ at Leicester cathedral during Black Lives Matter protests in 2020”. Graham Usher, Bishop of Norwich, is “a committed environmentalist – he is the lead bishop on environmental issues – and voted in favour of services to bless same-sex couples”. Rachel Treweek, Bishop of Gloucester, is spoken about in glowing terms – surely she must be a contender, believing in a non-binary God?

Treweek was the first woman to be appointed a diocesan (senior) bishop in 2015 and was the first female bishop to sit in the House of Lords. She has said that she believes God to be neither male nor female, has criticised the C of E’s lack of diversity, and has campaigned around negative body image among girls and young women. She is 61.

Paul Williams, Bishop of Southwell and Nottingham, isn’t looked on quite so favourably. This “conservative evangelical” is “associated with those in the C of E who are resistant to change and want to see the church affirm “orthodox” teaching on issues such as sexuality”. Finally, Rose Hudson-Wilkin, Bishop of Dover, gets the vote:

Born in Jamaica, in 2019 Hudson-Wilkin became the first black woman to be appointed a bishop in the C of E. Some progressives would be delighted if she were appointed to the top job as a powerful symbol of change. But there are many factors against this: her age (63); the fact that she is a suffragan (junior) bishop; her criticism of what she describes as the C of E’s “institutional racism”; and her tendency to speak her mind on most issues.

This interest in identity politics and woke talking points is not confined to The Guardian. It comes from the CoE itself. The Church Commissioners’ 2024 document on “Our approach to diversity, equity and inclusion”, for example, shows a similar shift of emphasis from religion to optics. The word “faith” is mentioned three times in a nine-page document (and only in the context of assuring the reader that “very few of our staff roles carry a religious faith requirement. We have talented, committed staff who come from a range of faiths and many with no faith and, regardless of this we all work to supporting the Church of England’s mission and ministries”). There is one passing mention of Jesus Christ towards the end, no mention of the Bible, and no mention of God. The CoE website claims that the Church Commissioners for England “support the Church of England’s ministry” by managing their endowment funds and supporting the “Church’s mission and heritage”. The lack of reference to religion in the DEI document is therefore perplexing.

Welby himself has been a lightning-rod for criticism of the soft liberal version of the Church of England. He apologized for the Church’s “institutional racism” and vowed to address its “shameful past” in the international slave trade. This includes turning a £100 million financial commitment into a £1 billion fund to atone for “moral sin”, which entails investing in black-led businesses and providing grants.

Welby has also affirmed transgender guidance for children. He rejected calls to scrap the CoE’s “Valuing All God’s Children” (VAGC), which covers 4,700 CoE primary schools, claiming: “This guidance helps schools to offer the Christian message of love, joy and celebration of our humanity without exception or exclusion.” “Valuing All God’s Children” was first published in 2014 in response to research on homophobic bullying in Church schools. It was re-written in 2017 and then updated again in 2019.

In a statement released by the CoE in October 2022, the aptly named Revd Nigel Genders defended the document. He claimed that the issues were raised in preparation for secondary schools (because the Church of England taking it upon themselves to provide trans guidance for 11 year olds is clearly more apposite). And yet page 20 of VAGG states:

In creating a school environment that promotes dignity for all and a call to live fulfilled lives as uniquely gifted individuals, pupils will be equipped to accept difference of all varieties and be supported to accept their own gender identity or sexual orientation and that of others. In order to do this it will be essential to provide curriculum opportunities where difference is explored, same-sex relationships, same-sex parenting and transgender issues may be mentioned as a fact in some people’s lives.

As Anglican.Ink reports, “this statement is on a page specifically addressing issues for CofE primary schools, and therefore the treatment of pupils as young as five years old”.

Instead of “Valuing All God’s Children” by discussing same-sex relationships and transitions with toddlers, the Church of England needs to think about preventing real abuse. The John Smyth scandal has sent shockwaves through the community. Let’s hope it will spark urgent conversations about keeping children safe.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.