It took me a while to realize that the rope-wrapped, stone-like form directly opposite Cambridge railway station was a sculpture. Ariadne Wrapped (2022) by Gavin Turk was unveiled in 2022, and is the first impression of the medieval university town for train-travelling visitors.

Guvin Turk: Ariadne Wrapped (2022)

Anticlimactic is not enough. The sorry scene is almost unnoticeable as a piece of art. Only its plinth indicates its status as artwork. Two years since its unveiling and it continues to resemble a construction site, but without the promise of completion. People pass by without a glance.

Its invisibility raises questions about the role of public sculpture in urban spaces. This particular work by Turk was commissioned by Brookgate development company following consultations with various groups, including the Cambridge City Council Public Art Panel and a Public Art Steering Group. Since the 1970s, scholars of museum studies have argued for the gallery “public” to be understood in plural form (“publics”), in order to account for differentiated visitor composition. Representatives on public art panels must consider the varied stakeholders. Inevitably, some people will be excluded from the “public”, given unlimited diversity. In other words, the preferences of some people will be prioritized over others.

The tension underlying definitions of the “public” is important to consider in light of inclusivity and diversity targets. To be inclusive suggests welcoming the widest possible public, whilst diversifying implies identifying distinct subsections of the “public” and speaking to their specialist requirements. Art that sits in urban spaces constitute daily material encounters for those who live nearby. Public sculpture therefore becomes personal.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

Recognition of the public-personal intersection helps to explain the seemingly democratic selection, involving various community representatives, that resulted in the commission of Ariadne Wrapped. The ideas behind the sculpture are interesting. Its form recalls the reclining female nudes represented throughout history. Turk subverts the recognizable pose – reworked for modernist sculpture by Henry Moore – in order to raise questions about its notoriety: “Wrapped and secured with ropes, she seems to be in transit”. The female form itself is not visible because she is wrapped in a sculpted bronze-painted sheet. Concept is therefore central to the sculpture. It deconstructs the form it seeks to interrogate.

The unfortunate result is that the fact of Ariadne Wrapped being a sculpture is… well, concealed. Concept – or idea – is prioritized by the artist over aesthetic value. Language comes before form, and the viewer requires art literacy in order to understand the concept. Conceptual art as public sculpture is not fit for purpose in urban spaces because it denies both its “public” and its existence as sculpture.

Even in gallery spaces, conceptual art has famously been the subject of public furor.

Media reaction to the Tate acquiring a pile of bricks – officially called Equivalent VIII (1966) by Carl Andre – testifies to this fact. Four years after the artwork’s acquisition, The Sunday Times’ headline “The Tate drops a costly Brick” sparked controversy, and Andre’s pile of bricks became a talking point about how best to spend taxpayers’ money. Technically, Andre is a minimalist rather than a conceptual artist, but to the outside observer the artwork was a pile of bricks with a heavy price tag.

Carl Andrew: Equivalent VIII (1966)

Conceptual art is typically traced to the French artist Marcel Duchamp (1887—1968). His series of “readymades” – “found” objects that he claimed as artworks – raised interesting questions about the nature of art and its market value. Artistic appraisal was based on the idea rather than the object. When art objects are displayed in gallery spaces their status as artwork is affirmed even before visitor interpretation. To create Fountain (1917), Duchamp took a urinal, signed it, titled it, and declared it “art”. The Tate acquired a replica (1964) in 1999, further nestling its legacy within the history of art.

Marcel Duchamp: Fountain (1917)

The symbolic capital of the Tate is important. If the urinal was dumped on a street corner, then it would be interpreted as an object at best, and fly-tipped rubbish at worst. The same can be said of the latest Turner Prize Winner, Jesse Darling, who effectively won with a room of trash. However, the gallery setting – constituting a “sacred” space apart from the “everyday” – demarcates the trash as an art installation. Urban spaces provide no such context, and this is a serious barrier for the display of artworks that seek to deconstruct their very being as “art”. Prior knowledge is required to consider conceptual or minimalist objects as artworks. Lacking a gallery space, the status of Ariadne Wrapped as “artwork” is not publicly accessible, except for the learned few.

Jesse Darling’s Turner Prize-winning work

Modernist processes of reduction in the 1960s lay behind the resultant unintelligible artworks, such as those described above. Although Darling’s Turner Prize-winning work was highly political, it fails to speak for itself because it relies heavily on description. In the past, activist artists resisted the exclusive nature of Modernist art for this very reason. Politically-motivated artists in the 1970s reasserted the primacy of figuration – representations rooted in recognized experience – in order to communicate their demands.

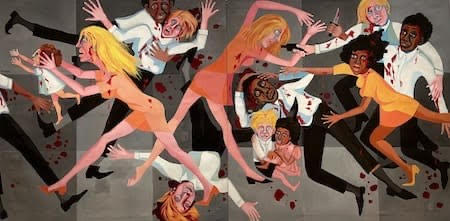

Faith Ringgold (1930—2024) articulated aspects of the African-American experience by appropriating Picasso’s Guernica (1937) for her own activist purposes. The resultant American People Series #20: Die (1967) conveys a clear message: blood splattered adults attack each other, whilst two innocent children – one black, one white – hold each other, terrified by the racial conflict around them. Ringgold successfully recognized the narrative power of images. Similarly, stained-glass windows illustrated Biblical scenes for illiterate worshippers before widespread literacy. Images translate ideas, rather than the other way around. Figuration requires skill gleaned from close observation and undergirded by creative intention – the ability to transcribe reality into a different form in a way that is comprehensible to the viewer.

Faith Ringgold: American People Series #20: Die (2017)

Frank Rutter in Evolution in Modern Art (1926) distinguishes between art which is “controversial and displeasing to the majority” and the “art of respectful plagiarism […] perfectly intelligible, widely comprehensible […]. It consists of doing the same old things in the same old way because our forefathers did them in the same old fashion.” Figurative art clearly falls into the latter category because it communicates a message – or, at least, declares itself as an artwork as part of a studied trajectory (i.e. the intentional creation of a human).

Galleries may be able to provide context for conceptual art by demanding its interpretation as an artwork as part of a curated space, and in doing so it becomes part of a wider art history. The problem with Ariadne Wrapped and deconstructionist art is that it lacks all artistic conviction. Without the gallery context, sculpture that deconstructs its very purpose is not contextualized as art. For a sculpture to be seen as art in a busy place, such as opposite a railway station, it must captivate the passerby. Beautiful art is democratic in this sense because it speaks for itself.

In this article I have taken a broad definition of “art” because I have confidence in contemporary artists, radical media, and nonconventional subject matter. Nevertheless, this broad definition has limits: art must declare itself as art in the first place (or at least rely on the gallery setting) in order to prompt reflection on the world. Public art should be accessible as art, and only then can it be inclusive.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.