“Romanticism in painting is political; it is the echo of the cannon shot of 1789”, wrote Auguste Jal. Translations of the original French phrase differ but the sentiment remains the same. For Jal, art was the manifestation of political and social transformations born of the French Revolution. Powerful images, such as Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix, symbolise this revolutionary fervour of the French Republic.

Delacroix’s painting resembles the photograph of Trump taken by Evan Vucci, the chief Washington photographer for the Associated Press, at the Pennsylvania rally. Described as “undeniably one of the great compositions in U.S. photographic history” by The Atlantic, Trump punches his fist in the air, two stripes of blood swiped across his face, with mouth wide open in call to fight. Similar scenes in oil paintings and movies are familiar, but to witness a display of strength in a moment of terror is rare.

Amidst innumerable campaign images this photograph has become symbolic of the election. Photographs in newspapers typically serve to illustrate text; the one taken by Vucci speaks without words. The American flag flies in the background, reminiscent of the tricolour flown by Liberty. Bodies gravitate forward as participants in the action that unfolds. Some shove, others push. Each composition follows a triangular structure peaked by the raised hand of the illuminated central figure, clearly the protagonist.

In both, a face stares directly towards the viewer on the right-hand side: a young revolutionary for Delacroix and a bespectacled Secret Service agent for Vucci. It is difficult to interpret the expression of either. Both mouths are caught slightly open and off-guard, taken aback by our voyeuristic gaze. Different struggles constitute the remaining characters. Animated expressions of consternation, concern-cracked composure, revolution, and rage.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

The artful orchestration of Liberty Leading the People reflects its extended period of production. Delacroix painted the work in the Fall of 1830 over a period of three months. He blends Romanticism with Realism: Liberty herself is an allegory, speaking to an imaginary scene, whilst the fighters are those who partook in the July Revolution. His ability to capture the emotions of action – pained expressions and dramatic gestures – speak to a training in life drawing infused with imaginative flair.

In contrast, Vucci captured his photograph in an instance. He reports rushing to the stage to capture everything he could. Susan Sontag describes the imperial scope of photography: “From its start, photography implied the capture of the largest number of subjects. Painting never had so imperial a scope.” Photography promises the democratisation of experience: we are now political participants whether attending the Pennsylvanian rally or not.

Photographs – since their invention in the nineteenth century – have been discussed in terms of objectivity and valued for documentary purposes. Early pioneers used the camera as a tool of social change because it could capture the horrors of industrialisation to a more precise degree than other artistic media, such as painting, sculpture, or drawing. Moreover, photographs constitute a heightened indexical immediacy. Photographic technology transfers light, from subject to eye of the viewer, much more quickly than alternative modes of artistic production. The gap between action and production is brought closer together, foreshortening the opportunity for artistic imagination to intervene, and in doing so producing a seemingly more accurate or “truthful” representation of reality.

The development of photography resonates with a History of Art striving towards realistic representation, provoking questions of artistic value, and with repercussions for the symbolic potential of Vucci’s photograph. Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24–79) wrote about a competition of the fifth century BC to discover the best artist. Zeuxis created a picture of grapes that was “so successfully represented that birds flew up to it”. However, it was his fellow competitor, Parrhasius, who was crowned champion for painting a curtain so realistic that Zeuxis tried to pull it back. Zeuxis had fooled the birds, but Parrhasius had fooled a man. Realism is illusionism insofar as it tricks the viewer.

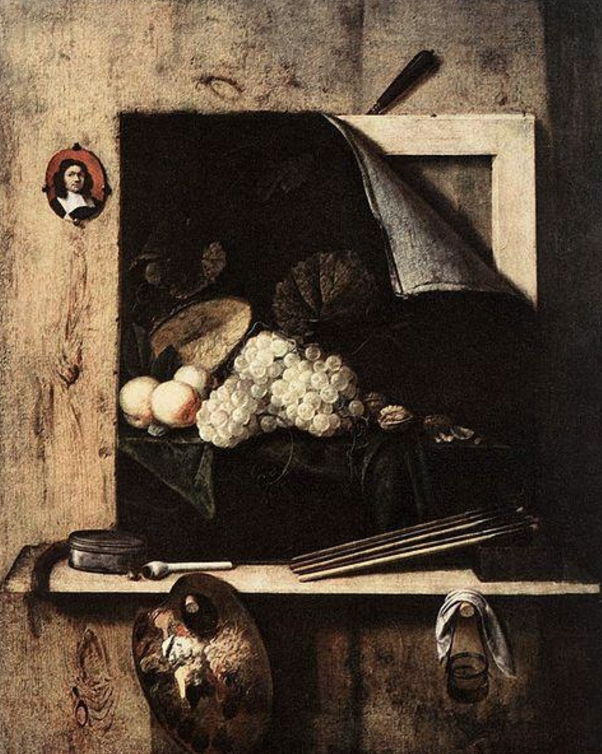

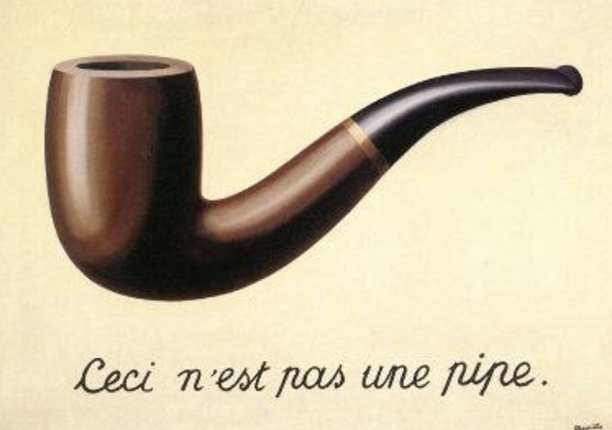

This theme continues throughout the whole of art history – from the trompe l’oeil paintings of the seventeenth century, such as Still-Life with Self-Portrait (1663) by Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, to the word-image paintings of twentieth-century Surrealists, such as Rene Magritte’s famous painting of a pipe. However, mimetic representation has increasingly lost its primacy as a value of art. The realism of Magritte’s pipe serves a different aim: to interrogate the relationship between word and image, rather than to fool the viewer.

Mimesis fell out of fashion because photographs could address the gap between material reality and pictorial representation to a greater degree than other artistic media. The French critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-67) feared that photography would replace painting completely. He warned, “If photography is allowed to deputize for art in some of art’s activities, it will not be long before it has supplanted or corrupted art altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the masses, its natural ally.” The mimetic function of art was threatened.

Artists and critics reacted against the introduction of photography in various ways. It curtailed Realism, the depiction of working-class subjects and everyday scenes for political purpose, as a fashionable artistic movement. Realist painters such as Gustave Courbet (1819-77), Jean-François Millet (1814-75), and Honoré Daumier (1808-79) rejected the artificiality of Romanticism, choosing instead to portray everyday life, sometimes on the grand scale of History paintings. The French historian and philosopher Hippolyte Taine (1828-93) urged readers to “Give up the theory of constitutions and their mechanism, of religions and their system and try to see men in their workshops, in their offices, in their fields, with their sky, their earth, their houses, their dress, their tillage, meals, as you do when, landing in England or Italy, you remark faces and gestures, roads and inns, a citizen taking his walk, a workman drinking…”. In other words, artists should use the same alienated eye as when visiting a foreign country to depict scenes of everyday life.

By seeing everyday life afresh, social problems would not be banal, but arresting and urgent. Realist artists strove to quit drawing from imagination in order to document society as a means of political protest. Take The Stone Breakers (1849) by Gustave Courbet as an example. It depicts two peasants breaking rocks on the ginormous scale (1.5 m × 2.6 m) previously preserved for “higher” subjects. The detail is minute and almost photographic, whilst the subject itself appears mundane, insignificant, and drawn completely from observation. It illustrates Courbet’s dismissal of Romantic elements: “an object which is abstract, not visible, non-existent, is not within the realm of painting”. Similarly, Adolph Menzel’s Procession in Hofgastein (1880) looks like it’s been accidentally captured. The unedited nature of the composition – a mismatch of peasants and injured persons, such as crutch-bearing men, hobbling alongside the better dressed Catholic clergy – attempts to gloss the finished product with a glean of scientific objectivity.

Delacroix is often penned “the leading exponent of Romanticism in French painting”: the type of artist who Courbet would have rebelled against. However, Liberty Leading the People is different for its depiction of working-class subjects (or revolutionaries) in almost photographic execution. The driving force of ideology – symbolised through the allegorical Liberty – animates the figures in the painting. Delacroix himself saw pictures, like music, as being “higher than thought”. In this instance, thought is ideology and is a driving force behind the action, propelled by the promise of liberty. Vucci’s photograph attains its symbolic power within this historical trajectory: a realistic medium used to produce an image that looks Romantic. Political fervour propels Trump to rise above the crowd, illuminated, despite the attempt to shoot him down.

The Pennsylvanian scene resembles one that would be painstakingly painted by Delacroix across several months. Processes of production are important to interpretating the final image. T.J. Clark argues that “The making of a work of art is one historical process among other acts, events and structures – it’s a series of actions in but also on history”. Accordingly, we can ask how this failed assassination became an image. The Romantic imagination of the artist – a liberty deployed by Delacroix through the medium of oil paint – is sacrificed for the immediate indexicality of the photograph. Consistent with the advice of Courbet, the image depicts what happened in real life, without any “non-existent elements”. The various other photographs of the same scene corroborate this reality, dismissing any suspicion of AI interference.

Hundreds of photographs capture this same event. That Vucci could capture the image of the election testifies to his experience as a photographer. One can only imagine the panicked confusion of the crowd in a rushed reaction to the gunshot. At this crucial moment, Vucci instinctively pushed forward towards the drama. He neither flees, nor protects, but lingers at the foot of the podium. The power of the resultant image suggests his own professional status and statis as photographic documenter.

Around the time of painting Liberty Leading the People Delacroix wrote, “My bad mood is vanishing thanks to hard work. I’ve embarked on a modern subject—a barricade. And if I haven’t fought for my country at least I’ll paint for her.” Delacroix writes and paints himself into the 1830 revolution. Similarly, Vucci’s participation is characterised by his non-intervention. Especially compared to the Romantic persona of the artist – Byronic or Goethean self-obsession – the objective appearance of photographs distracts from the creator: the lens acts as a veil, and in doing so foregrounds Trump as the primary aspect of interest.

Perspective places us below the podium looking up, meaning that we witness the event as a member of the crowd. Political outlook profoundly affects the visceral reaction experienced by the viewer in this envisaged relation. Susan Sontag wrote, “What determines the possibility of being affected morally by photographs is the existence of a relevant political consciousness.” Certainly, interpretations of the photograph differ according to individual perception, including when the image was viewed. To Democrats during the campaign, the image was the bubbling of violent ideology concretized on the surface, or the stealing of media limelight. Post-election, it is the symbol of Republican victory.

When Gustave Courbet produced Realist depictions of the working-class and peasant life in reaction to what he perceived to be a growing division between artists and the people, he made the bourgeoisie tremble. One critique called Courbet’s salon entry of 1851 – A Burial at Ornans (1851) which similarly depicted common people on a grand scale) – “an engine of revolution”. The silent yet powerful rumblings of what these images didn’t portray were able to alert bourgeois attention. In effect, reality lies outside of the image – the invisible crowd cheering for Trump, and the correspondent election results.

Trump is acutely aware of image. Snatched by a bullet he confronts his audience. His clenched fist is authority. Unlike Liberty, however, the Romantic self-presentation of Trump is not a myth. His swathe of policies and department creation lend credence to his post-victory speech: “Promises made, promises kept.” Democrat myth-making – empty promises that have been denounced by Ayaan Hirsi Ali – resonate with Romantic political ideologies. Photography is the perfect medium to unite politics with reality.

Vucci’s photograph captures a climax of powerful emotion so that we become voyeur to a vulnerable transient moment. The bloody material consequences of utopian ideologies – words, some assume to be spoken in jest – are laid to bear in the form of a photograph. Romanticism is left-wing idealism today, disconnected from what the public want. The power of Vucci’s photograph testifies to the new “engine of revolution”.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.