The subversions of the British Education system in Batley (2021) and Wakefield (2023) demonstrate on a small scale the tactics of Islam as laid down by Mohammed in the seventh century CE. There is a brutal simplicity to the three mechanisms which have ensured that Islam has spread across the world and through the ages, and which currently make it an urgent threat to British values.

The first is terror. Did Muslims sincerely set out to convince the people of Batley and Wakefield that they should revere a seventh-century prophecy? No. As with Pavlov’s dogs, the aim was not persuasion; it was to elicit the conditioned response of submission. The focus is always on the threat of violence. Because no individual was prepared to risk having their throat cut in Batley, Islam was given a complete victory. This breathtakingly simple tactic, it seems, cannot fail, as long as the threat can be made to seem real, as it inevitably does in the case of Islam. As Allah says in Quran 3:151, “We shall cast terror into the hearts of those who disbelieve” (trans. M. Pickthall). Or as Allah tells Mohammed in Ibn Ishaq’s Sira or Life of Muhammad, written about 760CE: “deal so forcibly with them as to terrify those who follow them, haply they may take warning… strike terror into the enemy of God” (trans. A. Guillaume, p. 326).

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

The second mechanism, death for apostasy as prescribed in Quran 4:89, featured prominently in Khomeini’s fatwa on Salman Rushdie in 1989. It creates an effective lock on the growing Ummah which, because of this mechanism, can never diminish in numbers. Nearly a dozen nations have death on statute as the punishment for “apostasy”, including several from which immigrants regularly arrive into Britain. Violence, intimidation by family members, and death threats are commonplace against those in Britain who leave the Ummah. The exercise of the fundamental British right to freedom of conscience is, it seems, denied to anyone in Britain born into Islam.

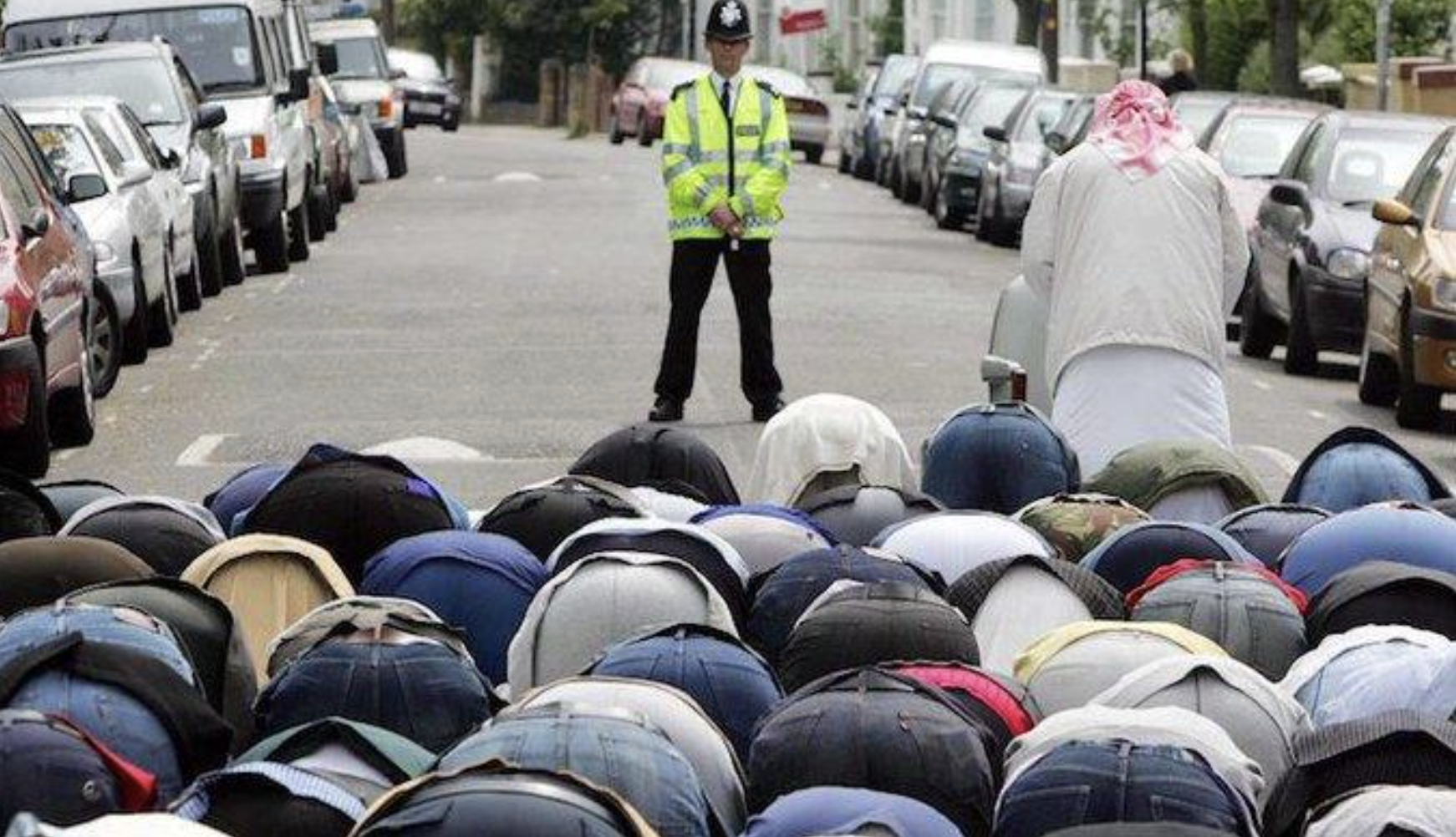

The third mechanism, the mass show of strength, was seen in the gathering outside the school gate in Batley. But its most effective manifestation is mass prayer. The psychological effect of this tactic in a nation like Britain, accustomed to the notion of prayer as an expression of private, personal commitment, is seismic. Mass prayer in Islam, unlike in other religions, is essentially a public show of power. Holding prayer meetings in parks or stopping traffic in the streets are effective ways to impress upon a host population that it has been subdued, at the same time as giving confidence to the believers that they have the whip hand. Who can hold out against the serried ranks of true believers, all men, each with a prayer burn on his forehead, all in the huddled posture of the medieval slave to his master? In Islam, the emotional Judaeo-Christian imagery of family, “children of God”, “Son of God”, is replaced by the more austere imagery of slavery. Abdullah, a common Islamic name, means “slave of God”. All true believers are slaves of God.

Birmingham, Eid 2018

London

There is no philosophical or theological content in this show of strength. It is a manifestation of raw power. The intended message is: “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em”.

Once introduced into society, whether in Birmingham, Luton, Bradford, Rotherham, London, or Oxford, or for that matter Paris, Berlin, Stockholm or Dearborn, Michigan, these three mechanisms, reinforced by a network of masjids led by the international Muslim Brotherhood fanatics preaching the Quran and an increasingly radical online congregation, will ensure that the ideology will continue to grow. All three elements come together in the Shahada or conversion ceremony: a public declaration made by saying: “I testify that there is no true god [deity] but God [Allah], and Muhammad is the Messenger and servant of God.” No other doctrines or subtleties of belief are involved. The spiritual conviction of the individual is lost in the public, ceremonial welcome. Should the believer change his mind afterwards, he must be killed.

The sacred book of Islam, central to events in both Batley and Wakefield, is at the core of a fundamental civilizational conflict. The rightthink of our European governments at present is that the Quran is a humane book, “hated”, like Muslims themselves, only by far-right racists, who offer a threat to British and Western far more serious than this scripture, which is revered by an embattled, vulnerable minority in need of protection. One problem is that almost no non-Muslims, and quite probably a large number of those who self-identify as “Muslim”, read this book. Most Westerners would be very surprised to discover its contents. Instead we remain willfully deaf, internalizing the doublethink our political leaders require of us.

One problem is that almost no non-Muslims, and quite probably a large number of those who self-identify as “Muslim”, read this book. Most Westerners would be very surprised to discover its contents. Instead we remain willfully deaf, internalizing the doublethink our political leaders require of us.

The current benign image of Islam and the Quran contradicts the view of the Prophet and his book generally accepted in Britain and the Western world until only two or three decades ago. The Quran, taught today as the final word of God in mosques across Europe, was judged by Western readers over many centuries to be full of hatred and violence. In the twelfth century, St Thomas Aquinas argued that while Christ gathered followers on the strength of his spiritual example, “Mohammed forced others to become his followers by the violence of his arms”. In the fifteenth century, the Byzantine Emperor Manuel Palaiologos gave a similar verdict. Mohammed commanded his followers to “spread by the sword the faith he preached”. In the seventeenth century, Blaise Pascal gave a neatly balanced version of this judgment: “Mahomet established a religion by putting his enemies to death; Jesus Christ by commanding his followers to lay down their lives” (Pensées, 1670). In the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment skeptic David Hume based his scathing verdict not on religion, but on humanist morality, declaring that Mohammed “bestows praise on such instances of treachery, inhumanity, cruelty, revenge, bigotry, as are utterly incompatible with civilized society. No steady rule of right seems there to be attended to; and every action is blamed or praised, so far only as it is beneficial or hurtful to the true believers” (Of the Standard of Taste, 1757).

The twentieth-century philosopher Bertrand Russell questioned whether Islam can properly be defined as a “religion” at all: “Christianity and Buddhism are primarily personal religions, with mystical doctrines and a love of contemplation. Mohammedanism and Bolshevism are practical, social, unspiritual, concerned to win the empire of the world” (The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism, 1920). Submission to Islam is more analogous to joining a gang than “converting” to a religion in any sense comprehensible in the West. George Bernard Shaw concluded briskly that in “Mahomet’s” religion “there was to be no nonsense about toleration. You accepted Allah or you had your throat cut by someone who did accept him, and who went to Paradise for having sent you to Hell” (Bernard Shaw, Collected Letters 1926-1950, 1988). And, as if to confirm the truth of Shaw’s aphorism, Theo Van Gogh, who satirized Islamic misogyny in the film Submission, made with my cooperation, was shot and stabbed to death in 2004 for showing verses from the Quran painted on a woman’s body. It seems that those in the West who have read this book have responded overwhelmingly with spiritual or moral contempt, or with fear of its terrorism. The disrespectful boys in Wakefield have a long and respectable tradition of Western responses to the Quran behind them.

The dishonest response today, in accordance with postcolonial theory, is to defend the Quran against ignorant “orientalist” attacks (see Edward Said, Orientalism, 1978). But considering the implications of Batley and Wakefield, can we be sure that these Western readers were simply wrong? Is it right instead for us to take seriously the claim that Allah sent an Archangel to tell a seventh-century warlord that those who refuse to submit to the Quran are subhuman, “the worst of beasts” (Quran 8:55, trans. M. Pickthall), and that “idolaters” (Pickthall) or “pagans” (Yusuf Ali) who do not observe the Abrahamic prophetic tradition must be exterminated unless they convert to Islam (Quran 9:5)? This is the verse cited by ISIS to justify its genocide against Yazidis in 2014 (Nadia Murad, The Last Girl, 2017). Are we to accept that Jews and Christians are “evildoers” (trans. Arberry), with whom believers should never be friends (Quran 5:51)? Should we respect Allah’s command to Mohammed to “admonish those who say that God has begotten a son”? “Whatever they say about [this matter] is vicious blasphemy and plain lies” (Quran 18:4-5, trans. Mohammed Sarwar). These verses are particularly problematic in a nation with an established Christian religion, headed by the King.

There is clearly “hate” in some of these verses; but the notion we are now told we must accept, that there is “hate” in rejecting them, is very recent and difficult to comprehend. We are in the absurd position of being accused of “hate” for criticizing a book filled with hate. If we argue the case from the text, we are accused of harboring a “phobia” against Islam and cancelled, and perhaps in the near future will be prosecuted. In effect we are conquered.

Consider the intellectual contortion demanded of those in the United Kingdom today by the term “Islamophobia”. Our elected political leaders have determined that fear of Islam must now be seen as a delusion or “phobia”, not as Edward Gibbon, historian of the military advance of Islam across the classical world into India and Europe in the millennium following Mohammed’s death, would have seen it, or as a Hindu in the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries would have seen it, or as a Northern Nigerian Christian today would see it – as a rational response to a physical threat.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Muslims’ Report on Islamophobia tells us: “Islamophobia is rooted in racism and is a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness”. This definition would be meaningless in the Indian subcontinent where Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Christians all share brown skin colour. There are fundamental genetic similarities between all the groups inhabiting the Indian subcontinent. But every Pakistani knows that, as a Muslim, he or she belongs in the “Land of the Pure” by virtue of religion. The APPG definition of “Muslimness” would be similarly meaningless in Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Iran, where the overwhelming majority populations, after centuries of wars of conquest, genocides, and pogroms, are homogeneously Muslim. Islam is not a race; it is an aggressive ideology.

The All Party Parliamentary Group also makes a fundamental category mistake. Though it does address religious prejudice against individual Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, or Somalis, for which it adopts the correct term “anti-Muslim hate”, it chooses as its headline the term “Islamophobia”, as though it were the religious ideology of Islam which needs protection against “racism”. In fact the Quran needs no protection. It is non-Muslims and ex-Muslims of all races who need protection against men acting on commands in the Quran.

But let us make a determined effort to be fair, and to follow the All Party Parliamentary Group in their concern to do justice to this ideology. Leaving to one side for the moment the problems of terror and violence, what are the distinctive features of this system of values? We should be able to judge these, surely, by examining the Declaration of Human Rights in Islam (Cairo, 1990) which sets out an Islamic alternative to the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Here we might hope to find the core values of this “world religion”, free from Western prejudice, “hate”, or phobia.

It is, however, a deeply disappointing document. As in the case of Edward Said’s theory, we seem in pursuit of a phantom. Said is brilliant at ridiculing the supposed malice of Western “orientalist” readings of the Quran, but never defends its words in their own right. As a religion involved in a centuries-long struggle with Christendom or the West, Islam, judging by this document, is forever doomed to see itself reflected in Western eyes. Its statement of “fundamental rights in Islam” is abjectly secondary, providing at all points a less-than-universal version of the original 1948 Declaration.

In the 1948 Declaration, every right follows inevitably from the very fact of being human. Such universality is rejected by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation since infidels are less than human according to Quran 8:55. Instead, every “human” right is dependent on “Shariah Law”, derived from the Quran, Sunnah, and Hadiths. This means, for instance, that without any derogation from “human rights”, signatory nations may condemn atheists to death, as happens in thirteen countries including Iran, Pakistan, and Qatar. Article 10 of the Declaration justifies this limitation of freedom of conscience by asserting that “Islam is the religion of unspoiled nature”. Consequently, “it is prohibited to exercise any form of compulsion on man or to exploit his [sic] poverty or ignorance in order to convert him to another religion or to atheism.”

Article 22 of the Declaration gives the impression that Islam grants all people the right to freedom of speech: “Everyone shall have the right to express his opinion freely”. But this is disingenuous. Freedom can be exercised only “in such manner as would not be contrary to the principles of the Shariah”. Signatory states may impose the severest punishments on anyone who doubts the account of Allah contained in the Quran. Unsurprisingly, “after its adoption, human rights activists in the West and some in the Muslim world claimed that the Cairo Declaration conflicted with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”. Any reader of the Quran could have forecast this. The rich diversity of rights in the Western “Universal Declaration” to believe in any religion, or to disbelieve in all, is denied in favour of the right, if such it may be called, to believe what the Quran tells us to believe. Non-Muslims might be excused for finding the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation’s document vacuous, as well as oppressive.

Comments (1)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.