On Monday 3rd February President Trump announced plans to cut all future funding to South Africa pending an investigation of land confiscations designed to affect “certain classes of people VERY BADLY.” The class of people Trump was referring to are the white farmers of South Africa now under threat from the recent introduction of a new Land Expropriation Act, signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa, which allows for expropriation without compensation (EWC).

The Act replaces the 1975 Expropriation Act which obligated the state to pay the owners of the land it wanted to expropriate for its various state projects. This is the principle of “willing seller, willing buyer” which Nelson Mandela had supported while at the helm of the African National Congress (ANC), South Africa’s ruling party.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

In response, the South African President asserted that the “South African government has not expropriated any land” and that the “Expropriation Act is not a confiscation instrument, but a constitutionally mandated legal process that ensures public access to land in an equitable and just manner as guided by the constitution.” It is worth looking at these claims and assessing just how widely the “just”, “equitable” and “in the public interest” safeguards will be construed by the corrupt South African regime.

Chapter 5 of the Act, at 12(3) does provide that “it may be just and equitable for nil compensation to be paid” for the expropriation of land and allows over 400 expropriating authorities to make their decisions on the basis of loosely defined criteria.

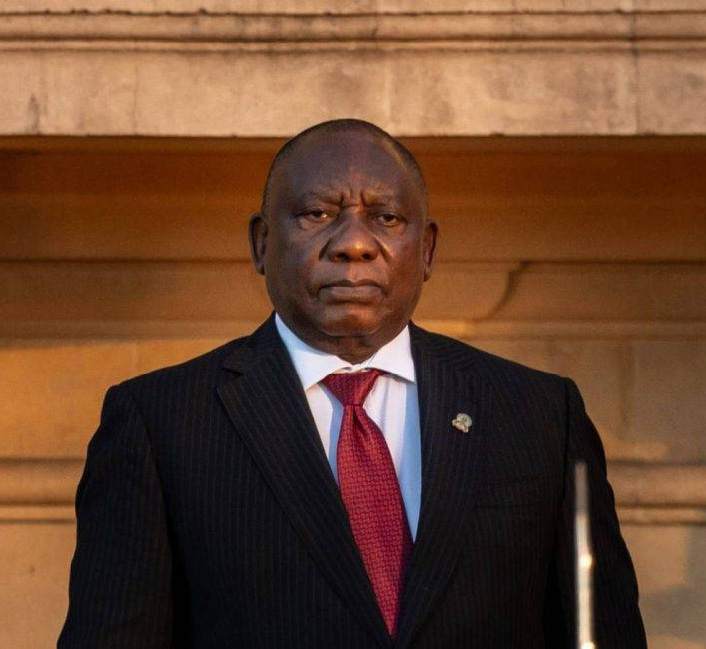

President Cyril Ramaphosa

But why would the government persecute the farmers?

When Mandela’s party, the ANC, came into power in 1994 after the fall of the apartheid regime, one of their flagship policies was land reform. The goal was to transfer 30% of South Africa’s white-owned agricultural land to black people by 1999 through buy-outs and subsequent redistribution. Some have estimated that around 20% of white-owned farmland has thus-far been redistributed. At least 72% of South Africa’s farmland is currently held by white farmers who make up less than 10% of the population. The ANC is committed to reducing this percentage, and the concern is that this will be done by force.

When Mandela rose to the premiership of South Africa to usher in what he hoped would be a “rainbow nation” post-apartheid, he adopted a markedly different approach to neighbouring Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. Mandela asserted respect for property rights (an essential criterion for a functioning rule-of-law state), expressing his attitude towards the whites in terms of mutuality and participation in the project of nation building:

“Our principal goal is a better life for all South Africans: black and white, farmer and farm-worker. The success of the Reconstruction and Development Programme requires a partnership among all social structures.” (1994 Address)

Mugabe, on the other hand, oversaw the mass displacement of, and violence towards, white farmers which crashed food production in the former “breadbasket of Africa” by 60% over a decade, contracting the economy by 18% per year by 2003. His appalling treatment of the white famers caused mass hunger and malnutrition among the population of Zimbabwe, a country which had previously been a net exporter of food. His justification was simple:

“The land is ours. It’s not European and we have taken it.”

Mugabe publicly criticised Mandela for being “too much of a saint” and being too soft on the whites. The acclaimed documentary Mugabe and the White African, is worth a watch on this subject.

The early pragmatism of the post-apartheid settlement seems increasingly to have been discarded as a host of race-based policies proliferated. The 1998 Employment Equity Act and then the introduction of Broad-Based Black Empowerment (BBEE) in 2003 saw White South Africans increasingly excluded from government contracts and high-level employment in the state and private sectors; by the 2010s the epidemic of violent “farm murders” reached international attention accompanied by the use of the chant “Kill the boer, kill the farmer” by senior figures at ANC rallies such as Julius Malema, who later founded the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), the third largest party in South Africa; and by 2017 the ANC formally called for land expropriation without compensation, now signed into law, while Malema continues to call for black South Africans to “occupy the land” owned by whites.

Julius Malema holding an EFF rally.

Where Mugabe’s drastic approach to the white farmer question in Zimbabwe shocked the international community drawing condemnation and spooking investors, the trend in South Africa suggests that the ANC has adopted a subtler way to march towards its so-called “national democratic revolution”. In the 2017 memoirs of constitutional lawyer and MP Dr Mario Oriani-Ambrosiani, we find an explanation of this approach from a conversation with President Ramaphosa himself:

“In his brutal honesty, Ramaphosa told me of the ANC’s 25-year strategy to deal with the whites: it would be like boiling a frog alive, which is done by raising the temperature very slowly. Being cold-blooded, the frog does not notice the slow temperature increase, but if the temperature is raised suddenly, the frog will jump out of the water. He meant that the black majority would pass laws transferring wealth, land, and economic power from white to black slowly and incrementally, until the whites lost all they had gained in South Africa, but without taking too much from them at any given time to cause them to rebel or fight.”

The understandable fear amongst the white farmers of South Africa is that opening the door to expropriation without compensation is bringing the pan to boiling point. SABC News has already reported on instances of land invasions directly inspired by the passing of the Land Expropriation Act.

There has already been a terrifying skills shortage in South Africa with nearly a fifth of the white population leaving since 1994. In a country where only 12.3% pay income tax, with almost half of the population, rising to 62% of the black population, drawing state grants, this is sorely felt.

South Africa existing as a redistributive state (animated by the ANC’s commitment to Marxist ideology) makes this march towards the dispossession of white farmers almost inevitable without the careful watch of the international community. The country is rapidly moving from being a constitutional democracy to a kleptocracy (rule by thieves) in which the rulers enrich themselves through control of state-owned enterprises and municipal authorities, maintaining power by redistributing loot and station and awarding lucrative state contracts to members of their particular client group. In a country where redistribution is the key to maintaining a powerbase, minorities such as white South Africans, but also the Indians and Coloureds, risk being used as a short-term source of bounty for politicians seeking to fulfil promises to their voters.

In this climate, racial tensions abound. In 2021 when former president Zuma was imprisoned, Zulu rioting erupted in Kwa-Zulu natal with supermarkets burned to the ground and swathes of the province looted. Footage emerged of violent confrontations and of Indian South Africans forming armed militia to protect their property. I remember friends stocking up on food provisions in anticipation of shortages and was on the phone to one while he attempted to source flights out for his parents as riots enveloped their town. It was the worst violence seen since the end of apartheid – not exactly the picture of harmony.

2021 rioting in Kwa-Zulu Natal.

The International Community.

This vision of South Africa today and the fears of its minority populations for the future can be difficult for Europeans and Americans to digest.

Our understanding of South Africa is frozen at that great moment Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as president after 27 years of imprisonment under the oppressive Apartheid regime. The image of Mandela, fist raised, beaming smile, is one of the most recognised symbols of freedom to this day, and represents, for many, the victory of liberalism at the waning of the 20th century.

The problem, however, is that we have become so obsessed with the end of history and the inexorable march towards progress, that the idea that South Africa, the very symbol of this, might slide carefully and deliberately into tyranny is shrugged off and ignored lest we be forced to re-examine our worldview. As such, triumph achieved, the west has practically washed its hands of South Africa and completely abandoned any questions which touch on institutions and nation building. Questions with which it had previously enthusiastically concerned itself.

And South Africa is important to the west for other reasons. The promised settlement, which emerged from the staid wisdom of Mandela and Archbishop Tutu’s dogged determination to achieve reconciliation, stood as a shining example for all prospective post-colonial and multi-ethnic nations. The “rainbow nation” and “multiculturalism” feel intimately connected. In school, we learnt about them together and we are reluctant to abandon hope in either.

South Africa is a country very proud of its human rights credentials and taken seriously because of our collective and selective understanding of its history. In 2024 international press fawned over South Africa as a human rights leader, heading the charge in the ICJ with its genocide case against Israel. The hypocrisy of the South African government on human rights and the treatment of its own minorities, however, receives only the slightest of attention or is largely ignored. In 2015 for example South Africa gave shelter to Omar Bashir, then dictator of Sudan, despite his being wanted for crimes against humanity, including genocide and torture of the people of Darfur. More recently, Ronnie Kasrils, the former intelligence chief described the October 7th attacks on partygoers in Israel as “a brilliant spectacular guerilla warfare attack. They swept in on them and killed them and damn good. I was so pleased and people who support resistance applauded”.

No number of New York Times op-eds about how “Kill the boer” is merely a sophisticated euphemism can disguise the fact that this genocidal rhetoric is commonplace among the South African political elite and is taken seriously by white farmers and minorities within the country. With the legal protections for these minorities deteriorating, it is about time the international community takes it seriously too.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.