Another week, another article about Cynthia Erivo. Erivo rocketed to international fame with her performance as Elphaba in Wicked, which I reviewed here. I was broadly positive about the film, but markedly less so about its pathological press tour and the hysteria about identity politics dogging the production.

Erivo’s latest role? Jesus Christ Himself. Yes, really. It has been announced that Erivo will play Jesus in a production of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar at the iconic Hollywood Bowl this summer. She will be the first woman to lead a high-profile production of JCS, which dramatizes Jesus’ final days before the crucifixion.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

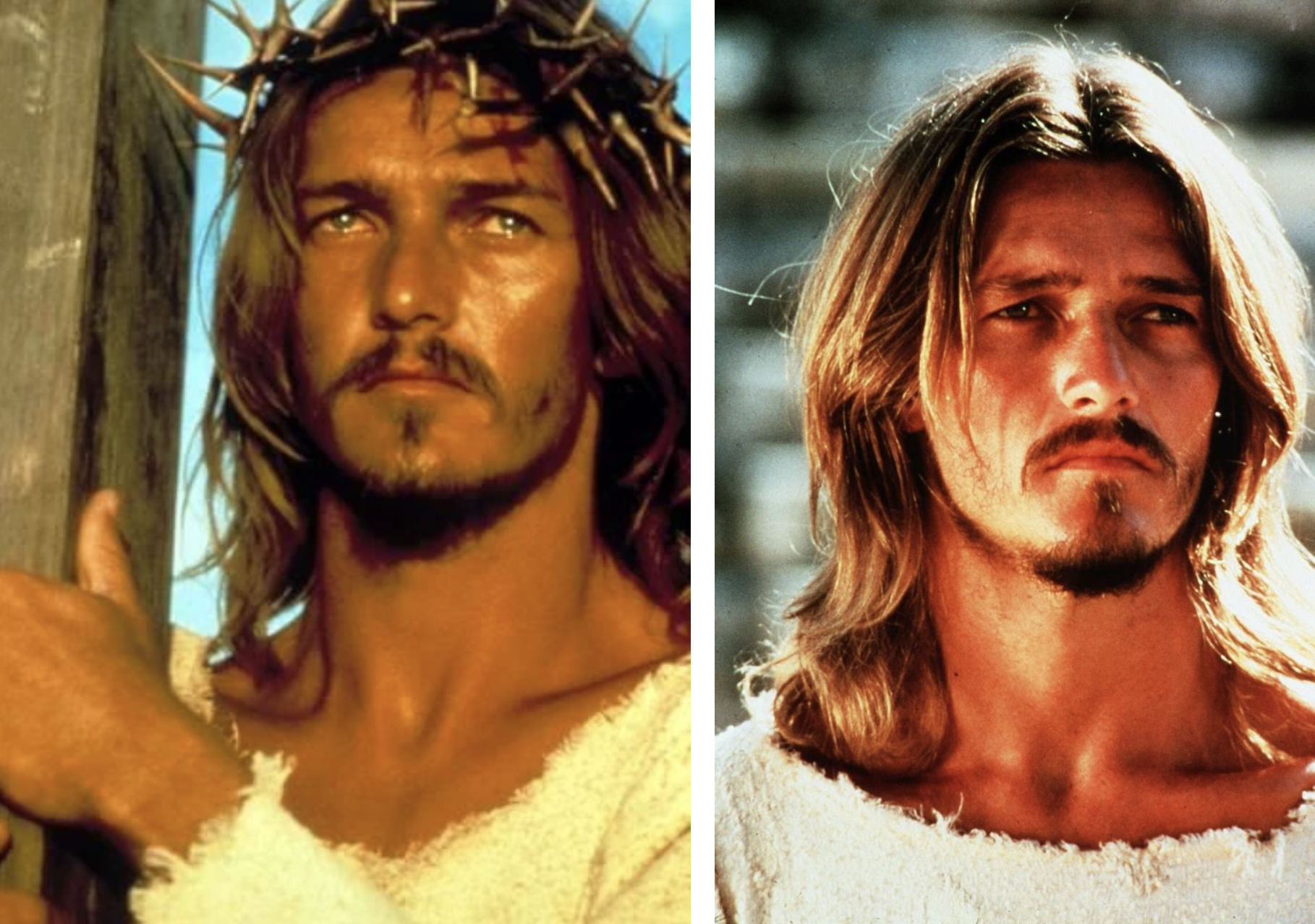

Long-time collaborators Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice first released Jesus Christ Superstar as a concept album in 1970, because no producers were willing to stage it. At this point they were only 22 and 25 years old, respectively. This was their second rock opera, the first being Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat in 1968. Jesus Christ Superstar proved a commercial hit and soon opened on Broadway. It gained further popularity due to the brilliant 1973 film with Ted Neeley as Jesus and Carl Anderson as Judas – both tour de force performances. Neeley’s rock-infused vocal style is raw and emotional, even including falsetto screams and snarls. His “Gethsemane” is anguished, showing Christ bargaining with God and accepting His fate. Anderson brings an R&B and gospel dimension to the mix, giving a superb vocal and theatrical performance, and the chemistry between the two leads is electric. The film was shot on location in Israel using vast desert landscapes. The costumes mix ancient biblical garb and 1970s flower power.

Another film of the rock opera was released in 2000, leaning more towards musical theater than pure rock. Glenn Carter stars as a more introspective and mysterious Jesus, contributing softer and more airy vocals. Jérôme Pradon plays Judas in a tortured performance, highlighting his highly strung and unstable temperament from the beginning.

As a self-confessed musical theater nerd, I was glued to this version of Jesus Christ Superstar in my childhood. I watched the 2000 VHS remake on repeat. Quite aside from the propulsive music, which is a masterclass in the genre of rock opera, this filmed studio production is unashamedly noughties in feel. Think military camouflage, white wifebeaters, mesh sweaters, fingerless gloves, unnecessary layering, and low-waisted combat trousers. Simon the Zealot even has frosted tips (and a tattoo of a crucifix, which feels a touch premature given that Jesus has gone nowhere near a cross at this stage). NSYNC apostles dart across the stage and the edgy editing style smacks of MTV. It is futuristic and punk-inspired.

The casting of a woman, Cynthia Erivo, as Jesus Christ in this much-loved musical was met with mixed responses. Given the availability of many brilliant, high-profile male singers, it is easy to see this casting as deliberately provocative: a drearily predictable attempt to rewrite the narrative. Even Jesus must be subjected to the relentless drive to diversify and deconstruct. Christians can be relied on to turn the other cheek, so to disregard their most cherished beliefs is safe enough.

Moreover, it is difficult to accept that the casting is “blind” when Erivo spends about 90% of her time foregrounding the fact that she is “black, bald-headed, pierced and queer”. I criticized Erivo’s emphasis on identity politics in “The Age of Emotional Incontinence”, arguing that her gender, sexuality, and color are entirely irrelevant. It is imaginatively limiting to insist on putting one’s own identity at the center of a fictional performance. What does the casting of Erivo add to any interpretation of Jesus Christ, we might ask?

Credit: Splash

It is nevertheless worth pointing out that some people criticizing the decision to cast Erivo may not have seen the musical. It has always courted controversy, irrespective of casting. Many flinched at the idea of presenting the Passion as a rock musical in the first place – this was why Webber and Rice had to release it first as an album. No one was prepared to stage the Passion in a musical theater performance. Indeed, when MCA Records released “Superstar” as a single in 1969, there was a religious backlash. Some radio stations even banned it. Martin Sullivan, then Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral and former Archdeacon of London, wrote a defense in his notes for the sleeve of the single:

“There are some people who may be shocked by this record. I ask them to listen to it and think again. It is a desperate cry. ‘Who are you Jesus Christ?’ is the urgent inquiry, and a very proper one at that…The singer says ‘Don’t get me wrong, I only want to know.’ He is entitled to some response.”

The Dean is aware of the complexity at the heart of Christianity: that Christ is both divine and at the same time human. Still, the characterization of JCS might unsettle. In the opera Jesus is humanized, psychologically complex, and vulnerable. The narrative is partly seen through the eyes of Judas, who is given a somewhat sympathetic treatment. We see him wrestle with his conscience, warning Jesus time and again that things are spiraling out of control. Crucially, the musical does not include the resurrection, but ends straight after the crucifixion. The romantic tension between Mary Magdalene and Jesus might also make some Christians bridle.

When the concept album was released in 1970, the BBC refused to play it for fear of offending. In 2021, Ted Neeley, the original understudy for Jesus on Broadway in the early 1970s (and of course, Jesus of the 1973 film), remembers the protests: “Every single performance was protested by people calling it sacrilegious. They would try to keep us from going in the stage door.”

The iconography in the 2000 interpretation might also add another layer of shock. It is punky and ultra-modern. It is also much more graphic than the 1973 film. Take Judas’ death scene. It opens with Judas’ horrified outburst to the High Priests and plea to reverse his actions after seeing Christ’s flogging (‘My God, I saw him, he looked three quarters dead’). He breaks into an impassioned prayer to Jesus himself (“Christ, I’d sell out the nation / For I have been saddled with the murder of you / I have been spattered with innocent blood”) and confesses his love, wondering “does he love me too”. He lapses into inarticulate howls. The rest of the scene is a dark crescendo: Judas’ sanity cracks and he decides to kill himself. To a throbbing, ominously repeated chromatic bass riff, Jérôme Pradon’s eyes lift to the camera. “My mind is in darkness now”, he whispers in harrowed tones, then cries loudly:

“… My God!

I am sick! I’ve been used and you knew all the time

God! I’ll never ever know why you chose me for your crime

Your foul, bloody crime

You… you… you have murdered me

You have murdered me, murdered me, murdered me, murdered me!”

He descends into guttural yells. We see a broken man lashing out at God. While plagued by guilt, he knows and resents the fact that he was necessary in order to fulfill the scripture (this was a possible reimagining of the theology as far back as the second-century gnostic Gospel of Judas). As he repeats “you have murdered me”, the platform rises up. A bloodthirsty mob gathers below, hungry for drama. His cries reach a fever pitch and a noose lowers. Sobbing, he puts it around his neck. It is the scene of a nightmare, the anonymous crowd baying below and a man in spiritual crisis. He jumps – we see the cord pulled taut. There is silence, then the hooded choir begins to sing a repeated refrain: “So long, Judas”. Christ’s crucifixion is also disturbingly graphic. It is not for the faint-hearted. Unlike in the 1970 film, the 2000 version shows us the brutality of the crucifixion at close quarters with nails driving into the blood-drenched flesh.

One number that stands out as the most shocking and potentially “blasphemous” is “Jesus Christ Superstar” itself. Christ staggers under the weight of the cross, blood streaming from the crown of thorns rammed onto his head. Judas, having committed suicide, re-appears as a nightmarish phantom dressed in bright red leather. He begins an upbeat number in which he questions Jesus, who is grimacing in agony and yet remains ethereally calm in the face of mockery. At one point Judas physically stands on the cross as Jesus tries to drag it.

The juxtaposition is deliberately distressing. Female back-up dancers strut alongside Judas, humiliating Christ who appears in a loincloth and drenched in blood. The cruelty is breathtaking and makes the Last Words from the Cross even more devastating when Christ utters them in the stillness after the song:

“God, forgive them – they don’t know what they are doing.

Where is my mother? Where is my mother?

My God, my God, why have you forgotten me?

I’m thirsty. I’m thirsty.

It is finished.

Father, into Your hands, I commend my spirit!”

As shocking as elements of JCS are, they serve a core artistic purpose: to bring the Passion to life onstage. The interpretation is meant to involve us in the drama of the story. It is difficult to see what the casting of Erivo in the role of Jesus will add to the previous versions, although she can certainly sing.

There are compelling reasons to believe that the casting decision was motivated not by artistic intention or the desire to illuminate the Passion, but ideology. Previously Erivo portrayed Mary Magdalene in a two-part album of the musical recorded by an all-female cast, orchestra, and engineers. It was given an inflammatory new title, explicitly feminizing the Scripture: She is Risen. The album cover is vaguely sapphic and doesn’t even mention Jesus Christ Superstar. It is patently obvious that this project was designed to further an ideological agenda rather than honor the original, or least of all pay attention to the biblical story. These women hijacked the musical – ironically written by two men for a predominantly male cast – and remarketed the Passion in order to put across an ultra-feminist message. An interview with the producers makes this clear. One mentions “how powerful we all are”, arguing that the album “goes hand in hand […] with the strides we have made as women”. Morgan James, the mind behind She is Risen, also claimed that “we are so in need of female voices and leadership right now”. Erivo’s 2025 casting can therefore be seen as part of a broader political trend. (Notably, her Wicked co-star Ariana Grande released the hit song “God is a Woman” in 2018. A pattern is emerging, and one which has no problem commandeering Christianity.)

There are clear double standards here. Christians are fed up with watching people play fast and loose with their faith while having to tiptoe around certain other religions. The 1979 Life of Brian was the focus of the same concerns about blasphemy, although its emphasis is more towards satire than illumination. It was Khomeini’s death sentence fatwa on Rushdie exactly a decade later in 1989 which breathed new life into the concept of blasphemy in our culture, and in a more sinister way. We are now all painfully aware that we are not allowed to mock all religions equally, whether for fear of causing social outrage, undercutting our public allegiance to multiculturalism, or crucially risking our safety. The fear of terror lurks.

Therein lies the rub: the cognitive dissonance of revering some religions while trampling on others with impunity. See, for example, the grotesque Paris Olympics stunt last summer. The opening ceremony evoked da Vinci’s “The Last Supper”, parodying Christianity with drag queens. Producers felt confident in opening the Olympics by mocking Jesus on a global stage. Did no one voice a whimper of dissent? Could you imagine the international outcry if Islam had been treated this way in so public an arena?

A recent experience brought this home to me. I was waiting for a train near Waterloo, London, and decided to wander into a restaurant bar to pass the time. Settling myself down at the counter, I raised my eyes to look at the huge uplit tableau dominating the wall. I was taken aback by what I saw:

With vague awareness of going full “Karen”, I asked to have a word with the manager. I pointed out to the sheepish man that this was mocking the Last Supper and asked why his restaurant would want to alienate any Christian coming through the door. Quite aside from religion, I don’t understand why the entire wall of an overpriced bistro would have that much gratuitous nudity. Any child could wander in with his parents and be confronted by an eyeful. But the real point, and what made the manager squirm, was my question as to whether his business would treat any other religion like this. Would it tolerate a mockery of the Prophet Muhammad up there, surrounded by lots of gyrating naked women (72 virgins, perhaps)? Awkward pause, then “no”. I asked why. More uncomfortable squirming, and I had the distinct impression that he felt afraid to say more. We both knew why.

Comments (1)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.