Of all the likely political tensions between London and Washington over the next four years, free speech is in a category of its own. To the new American administration, this is a fundamental principle as well as a national security interest. As Vice President Vance told shocked European delegates to the Munich Security Conference in February, Washington’s top concern is “the threat from within” the Nato alliance posed by European governments’ escalating assaults on “democratic values”, in particular their efforts to censor speech, quarantine popular opposition parties, and annul elections.

This was aimed in part at the Brits. The birthplace of Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights is regarded by Trump’s team as having fallen far from its lofty heritage; these days, its reputation among right-wing Americans is more that of a woke “anarcho-tyranny” where violent criminals are released from prison and illegal immigrants are put up in hotels while law-abiding citizens are locked up for speech and thought crimes. JD Vance accosted the British government in his Munich speech along these lines, highlighting the case of Adam Smith-Connor, a 51-year-old veteran who was convicted two years ago for silently praying for his aborted son within a 150-meter buffer zone around an abortion clinic.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

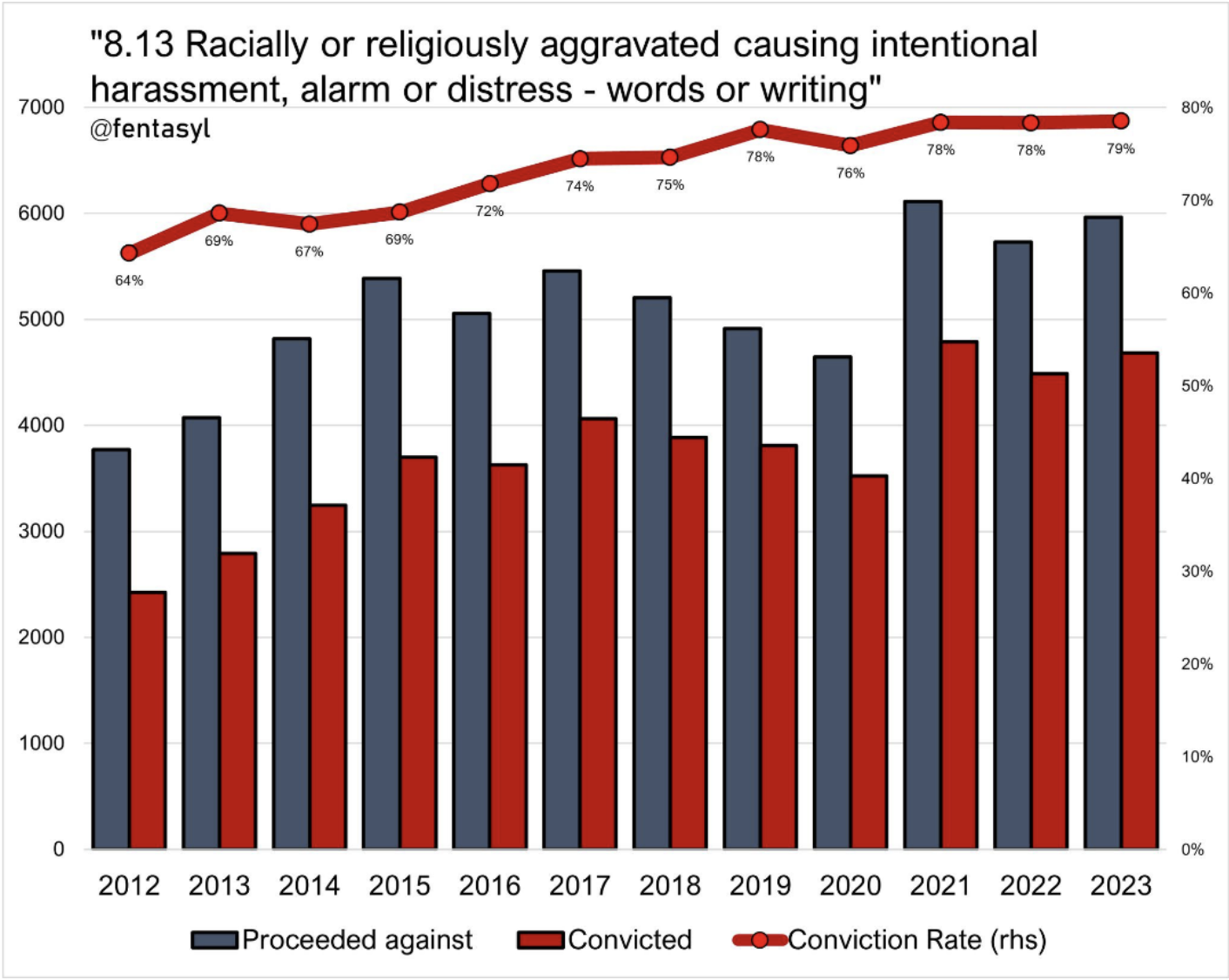

Pro-life expression is far from unique in being targeted by the censors. Vague speech offences have proliferated in Britain in recent years, even as speech authorities like the Office of Communications (Ofcom) have become more powerful. Since 2003, the Communications Act has prohibited undefined “malicious communications” and made it a criminal offense to “persistently make use of a public electronic communications network for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety” – all highly subjective offences. Other prohibited communications include incitement, causing “non-trivial psychological distress” and “stirring up” racial or religious hatred. In practice these broad offences have resulted in thousands of prison sentences for social media posts and memes, personal insults, public signs, and, as Vance noted, even prayers. During the ten years before Starmer took office, over 96,000 cases were brought and 72,000 convictions obtained for racially or religious aggravated speech alone, as you can see below.

This is outrageous enough from an American conservative perspective. But Vance’s emphasis on protecting expressive liberty in his Munich speech was not just rooted in moral commitment. It was also an implicit warning to the Brits and other European governments to retreat from the proxy war on democratic populism via speech policing that they have been engaged in ever since 2016. As the Vice President put it to Keir Starmer in the Oval Office on February 27th, “there have been infringements on free speech that actually affect not just the British … but also affect American technology companies and, by extension, American citizens”. Starmer struck a conciliatory note, denying any intention “to reach across U.S. citizens” with speech-related prosecutions, but his hosts have good reason to doubt these assurances given developments across Europe in recent years.

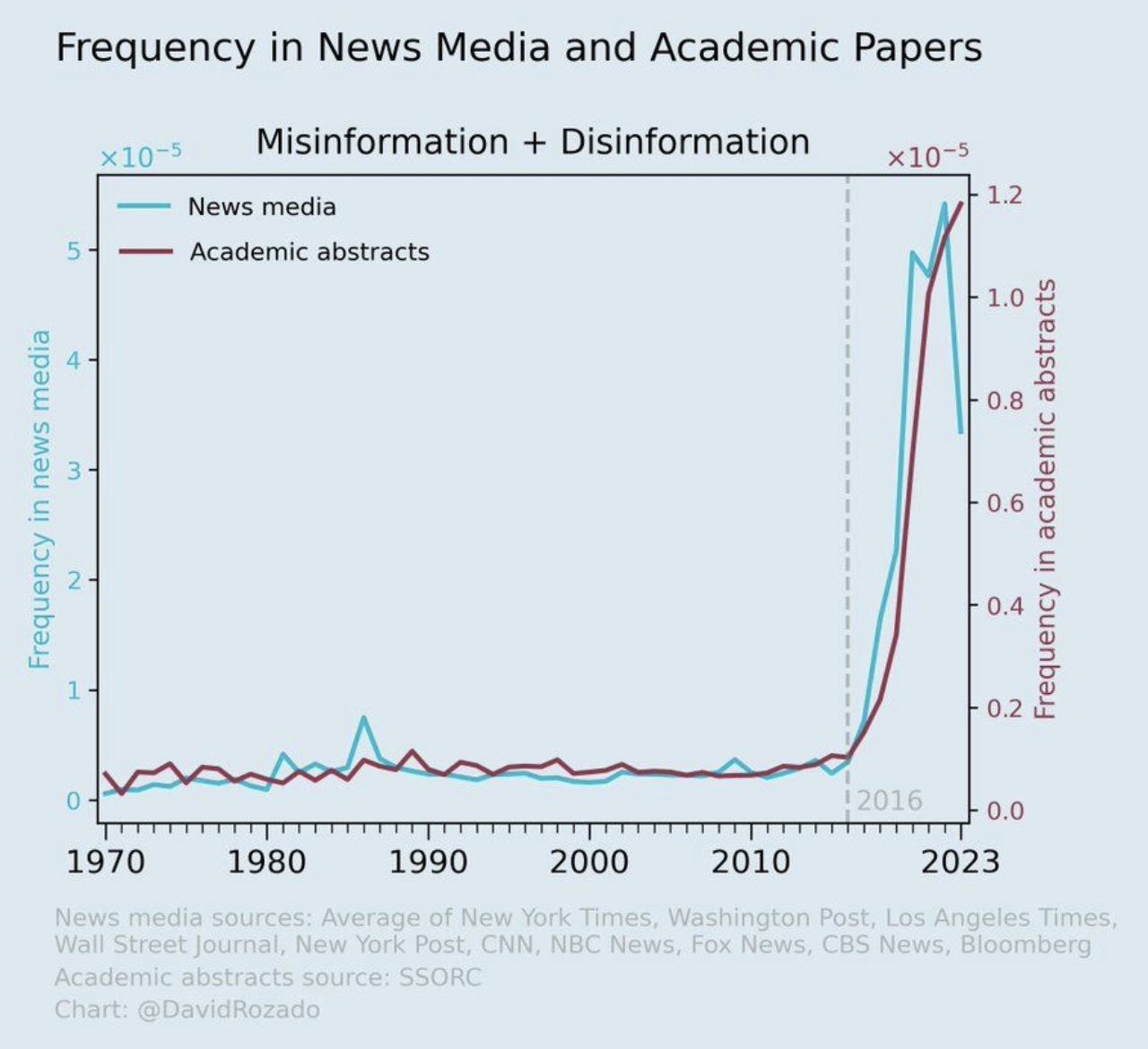

After Donald Trump’s first election victory and the Brexit referendum result, a panicked transatlantic establishment reacted by ramping up efforts to suppress disfavored speech and restrict the flow of online information. The underlying assumption was that their own increasingly extreme policy consensus could only be rejected by voters who were stupid or manipulated by “hate speech”, “misinformation”, and “disinformation” – terms which skyrocketed in the immediate aftermath of these upsets. So long as these were suppressed, the thinking went, people would stop voting the wrong way.

In the US itself, the First Amendment represented a formidable obstacle to this censorship project: as John Kerry complained before an audience at the World Economic Forum last year, “our First Amendment stands as a major block to be able to just, you know, hammer it out of existence”. A partial workaround during the Biden years was for the federal government to just ignore it by pressuring American tech companies to censor online speech for them, as revealed by the Twitter Files and confirmed by Mark Zuckerberg. Hilary Clinton put it to them bluntly: if social media companies “don’t moderate and monitor the content, we lose total control”.

But given the global interconnectedness of the internet, a subtler solution was found by outsourcing anti-populist speech policing to foreign countries without First-Amendment-type protections. The European Union took a lead on this, leveraging its huge market size and the regulatory “Brussels Effect” to try to force global internet content moderation in the desired direction. This culminated in 2023 with the coming into force of the EU’s Digital Services Act, which seeks to suppress the “spread of disinformation” and does so by threatening to fine any internet platform up to 6% of their annual global revenue if they fail to take down “harmful” or “false” content within a matter of hours. What constitutes “harmful” or “false” expression is, of course, determined by small groups of Platonic guardians chosen by the European Commission.

The UK followed suit with its own Online Safety Act in 2023, which created vague offences for online speech such as causing “needless anxiety” and “non-trivial psychological harm”. It also saw the growth of NGOs devoted to anti-populist censorship across borders. The Global Disinformation Index and the Centre for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), for example, both sprang up to focus on cutting off revenue to perceived right-wing sites by coordinating advertiser boycotts with politicized charges of “disinformation”. The CCDH – which was founded by Morgan McSweeney, now Chief of Staff at Downing Street – also lobbied US legislative staff to adopt STAR, a proposed “Global Standard for Regulating Social Media”, which it seemed convinced could provide the US with de facto hate speech restrictions by the back door.

What constitutes “harmful” or “false” expression is, of course, determined by small groups of Platonic guardians chosen by the European Commission.

This all came to the attention of the Trump team when British authorities and NGOs trained their fire on one specific American citizen and tech company owner: DOGE chief and X/Twitter proprietor Elon Musk. The Center for Countering Digital Hate managed to scare off many advertisers from Twitter after his acquisition of the platform, with leaked documents subsequently confirming that the NGO had “Kill Musk’s Twitter” as a top priority. The authorities also took aim at him after riots broke out last August following the murder of three white British girls by the son of Rwandan immigrants. Sir Mark Rowley, London’s Metropolitan Police commissioner, threatened to “come after” people in other countries for speech proscribed in British law, specifically mentioning “the likes of Elon Musk”, who, he alleged, was “whipping up hatred”. Labour MPs piled on by demanding measures against X, and Sir Keir Starmer himself weighed in to menace its owner by announcing that “large social media companies and those who run them” were responsible for “harmful disinformation”. “That is also a crime”, said the Prime Minister. “It is happening on your premises, and the law must be upheld everywhere.” And in theory, it could be: the 2023 National Security Act created a foreign interference offence which was extended by the Online Safety Act, and a company that falls foul of it could be fined 10% of its global revenue.

But picking a fight with the First Buddy over this issue, when he has both an adamantine commitment to free speech and a direct line to President Trump, could easily become a major source of tension between the two capitals. The US Department of Justice is already examining whether the CCDH – essentially a Labour Party cut-out – has engaged in a foreign influence campaign while failing to register as the agent of a foreign government. And were Sir Keir Starmer to give in to pressure from his own party by pursuing a Brazil-style ban on X, it could provoke full-fledged political and economic retaliation from Washington. Despite an otherwise inauspicious start for his government on the issue – they dropped a Tory bill to strengthen free speech in higher education, and recently demanded a backdoor into Apple users’ encrypted data – there are signs that Starmer is aware of this: the Telegraph has reported that the PM may be prepared to alter the Online Safety Act in order to avoid American tariffs. Although it will go against the grain of his own instincts, this suggests he grasps that “there is a new sheriff in town”, as Vance warned in Munich, and one who will not tolerate a continuation of the cyber proxy war on the speech rights of American citizens.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.