The nature of courage differs from bravery. In a communication from a reader of one of my columns in Canada’s National Post, I was praised for my “brave voice speaking out against some of the worst excesses of wokeism”. This is heartwarming, especially when it comes from a colleague in academia. It made me pause, considering the choice of words and prompting a dusty recollection of the Roman poet Virgil’s use of epithets in his epic, The Aeneid.

When retelling to Queen Dido of Carthage his experiences during the Trojan War, Aeneas, the hero of the piece refers to the great warrior Achilles as fortissimus, the bravest of the Greeks. But bravery is something instinctive, a reaction to dangerous or threatening situations where the protagonist has no fear, whereas courage is rather the morally upstanding virtue of taking certain actions in spite of fear, a fear that is recognized and felt but consciously rejected.

The Trojan hero Aeneas relates the story of the Trojan War to Queen Dido of Carthage. Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, 1815. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

When I set out to speak openly about the absurd antics that had swept across my campus at the University of Toronto, Canada’s foremost institution of higher education, I was merely brave on account of my blissful ignorance of the Machiavellian machinery that had quietly been arrayed against me. But having read much that has little or nothing to do with my chosen subject of chemistry, by authors I had never previously heard of, I came to realize the true danger; and it has most definitely filled me with fear. Fear for my own financial security, fear for what my colleagues and the students I teach might come to believe about me, fear of the impending academic apocalypse that has been underwritten by an inexorable shift towards the commercialization of our education system.

A common question I am asked by friends and colleagues – only some of whom, I soon learned, had my best interests at heart – is whether my travails on the university’s campus these past two years have taught me to despise the institution itself. The easy answer would be to nod glumly, but that would be the expected response, one driven by my emotion. Scientists are taught to be rational and examine the evidence. I can hear the late Leonard Nimoy’s voice in my head, “That would be irrational, Jim.”

Elsewhere, in The God Delusion, author Richard Dawkins recalls an emotional reconciliation when a senior scientist vigorously shakes his fellow scientist’s hand after the latter disabuses him during an invited lecture of a long-held but mistaken theory he had championed throughout his career.

With the benefit of hindsight, I cannot allow acrimony towards the institution fester and grow because it has, for all intents and purposes, done nothing wrong. The administrators who summon academics to in-camera meetings to “address concerns” or impose sanctions to correct for complaints must be held blameless. They are, after all, merely implementing the university’s policies in a manner that seems fair and equitable to them, and I have absolved them both legally and spiritually. After all, I have never denied what I said in the past, only what people chose to hear. But that does not mean I shouldn’t persist in challenging these people’s motives.

This attitude might appear unconscionably generous on the face of it, but an unemotional assessment of events throughout much of human history would throw up all manner of plausible deniability.

The camp personnel who punctured the lids of Zyklon B canisters at Auschwitz were merely following their routine orders. Topf & Sons were fine German engineers tasked with designing and implementing the first “mobile oil-heated cremation oven” at Buchenwald. We know the rest.

But how can blame be properly apportioned? Our scientific mind might deduce that accountability should be divided equally among all of the perpetrators. Our humanity might dictate very differently.

But I am an employee, and my employer has every right to reprimand me when I overstep the boundaries of acceptable professional behaviour; and I would never contest that reality, nor claim impunity. But what has become evident is the remorseless policy creep, and the refashioning of inclement interpretations and all-devouring narratives in the hands of the academic careerists.

Much of this foul weather emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic, when almost everyone straining at the end of their emotional tether said something uncharitable on more than one occasion. Students were anxious and curled up in their bedrooms nursing their perceived victimhood; and truculent professors sat at the dinner table with their laptops, repetitively clicking the unmute button and doing much the same.

Inevitably, then, student opinion surveys during that dark time were soon awash with vituperative remarks, seemingly unprompted ad hominems, and the pervasive hollow echo of widespread misery and despair. Once again, we might question who was to blame.

What is also contestable is my institution’s lack of appetite for forgiveness. I was always led to believe we were an institution of learning, one littered with ever more safe spaces where errors of judgement can be absolved. This turns out to be a delusion unless you happen to belong to one of the recognised marginal groups, and even then – I happen to be a white gay man – other visible features such as your skin tone might prompt your instant banishment into the oppressor group.

With all of this in mind, and with the encouragement of my colleague Jordan B. Peterson, an international phenomenon by that point, I turned my attention to writing about my experiences in the Post.

The first article I wrote was merely an ironic reaction to my cancellation from the university’s affairs, perceiving as I did with a renewed insight the utter foolishness that was engulfing what was on that occasion a departmental town hall, one where entitled students advanced specious claims and made vociferous demands in the name of social justice.

The piece caused a moderate stir and I pressed my advantage, doubling down on a well-trodden offensive strategy. Peterson had mentored me to strike hard and fast and often, and I took the advice. Peter Boghossian’s work on the Sokal Squared project was a revelation, and I became enraptured by his Spectrum Street Epistemology.

When the call came in 2024 for faculty in my department to preside over various activities at a student social event, I was genuinely enthused. Surely the students would revel in the opportunity to participate in debate, to strike different stances over issues of the day. And they were not to let me down.

But when I was called into my chair’s office to be reprimanded for transphobia, I began to realize how perilous my seemingly reasonable and rational position had become. I decided to record that meeting and I still listen back to reassure myself that, among other absurdities, my chair Lindsay Schoenbohm thought that debate ought to be limited to prescribed locations and that questioning whether “men can become women” made the department look transphobic. I should point out that in the province of Ontario it is a legal right to record any meeting that you are physically present for, even if the other participants are unaware.

But when I was called into my chair’s office to be reprimanded for transphobia, I began to realize how perilous my seemingly reasonable and rational position had become. I decided to record that meeting and I still listen back to reassure myself that, among other absurdities, my chair Lindsay Schoenbohm thought that debate ought to be limited to prescribed locations and that questioning whether “men can become women” made the department look transphobic.

I wrote a follow-up article to voice my satirical take on that meeting, where I was advised sagely that asking “whether pineapple belongs on pizza” was the acceptable limit of topics for debate in a social setting. And, no, this was not an authoritarian environment we were working in. How dull and contradictory and intellectually bankrupt. And, forgive me, how quintessentially Canadian, because kindness and compassion and good manners are practically pathological in this country. Yet I love Canadians, I really do; and I am married to one.

My next venture, then, was to reexamine my academic home turf and to contemplate some actions that, in retrospect, might now be cast as academic terrorism. I thought about it a good deal. I met some other of the dissenters across the campus. Then it dawned on me. I ought to decolonize my own subject. Organic chemistry, if the critics were to be believed, is fraught with white Eurocentrism. After all, the vast majority of the giants in the field were white-skinned, and male and, let’s not forget, German.

Now, in all frankness, I was undecided whether decolonizing one of the hard sciences was an altogether foolish and implausible enterprise, so I embarked on redrafting my curriculum in hopes of hunting down politically unfashionable topics like a scented bloodhound.

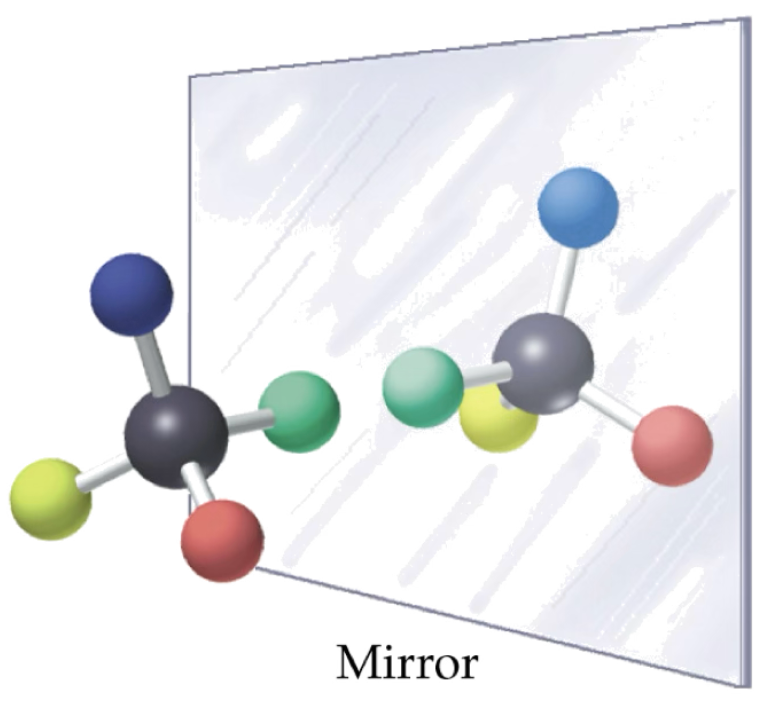

I was quickly rewarded. A sophomore textbook chapter on “stereochemistry” where science categorizes certain organic compounds into almost identical but spatially distinct pairs — much like so many pairs of gloves — and which we distinguish as left- and right-handed versions, instantly rewarded my attempts at linguistic reframing through a social-justice lens.

Molecules with certain geometries, when reflected in a mirror, are not superimposable on themselves. They are different, much like the left- and right-handed gloves that make up a pair. They are called enantiomers of each other.

In nature there are natural biases towards one handedness or another, depending on the family of molecules we look at. Amino acids are left-handed, whereas most natural sugars are right-handed. When we make such compounds in the laboratory, by default you get an equal mixture of the two forms, left and right. So, chemists are routinely equitable, at least until they attempt to mimic nature. But that is often the aim when it comes to synthesizing medicines. Should we point out and reevaluate these inherent biases? Only one in ten people in the human population are left-handed, after all. One in a hundred is ambidextrous. Can molecules be both? And how oppressive is this narrative to people who have no hands at all?

People with no hands, like Brian Gault, exist and live productive lives; yet their condition is a manifestation of a drug, thalidomide, with a stereochemical handedness. The left-handed enantiomer causes birth defects. Image courtesy of News Letter.

And then, if that were insufficient, there is the predilection of chemists to identify certain flat molecules called alkenes as either cis or trans. Oh dear. I can just imagine how that might play out in a classroom jam-packed with socially aware twentysomethings. Plus, we have the family of molecules called the esters. When we use a reaction to switch one ester into another, we call it transesterification. But when we prepare an ester from its constituent parts, an alcohol and a carboxylic acid, we term that merely esterification. Is that wrong? Shouldn’t it be cis?

I could go on. Certainly, there is a rich vein of bigoted material to be mined in the library of chemistry texts written almost exclusively by white men, and a lot of them are dead. It seems I must no longer bow before the headstone of the great Stuart Warren lest I be cancelled. Again.

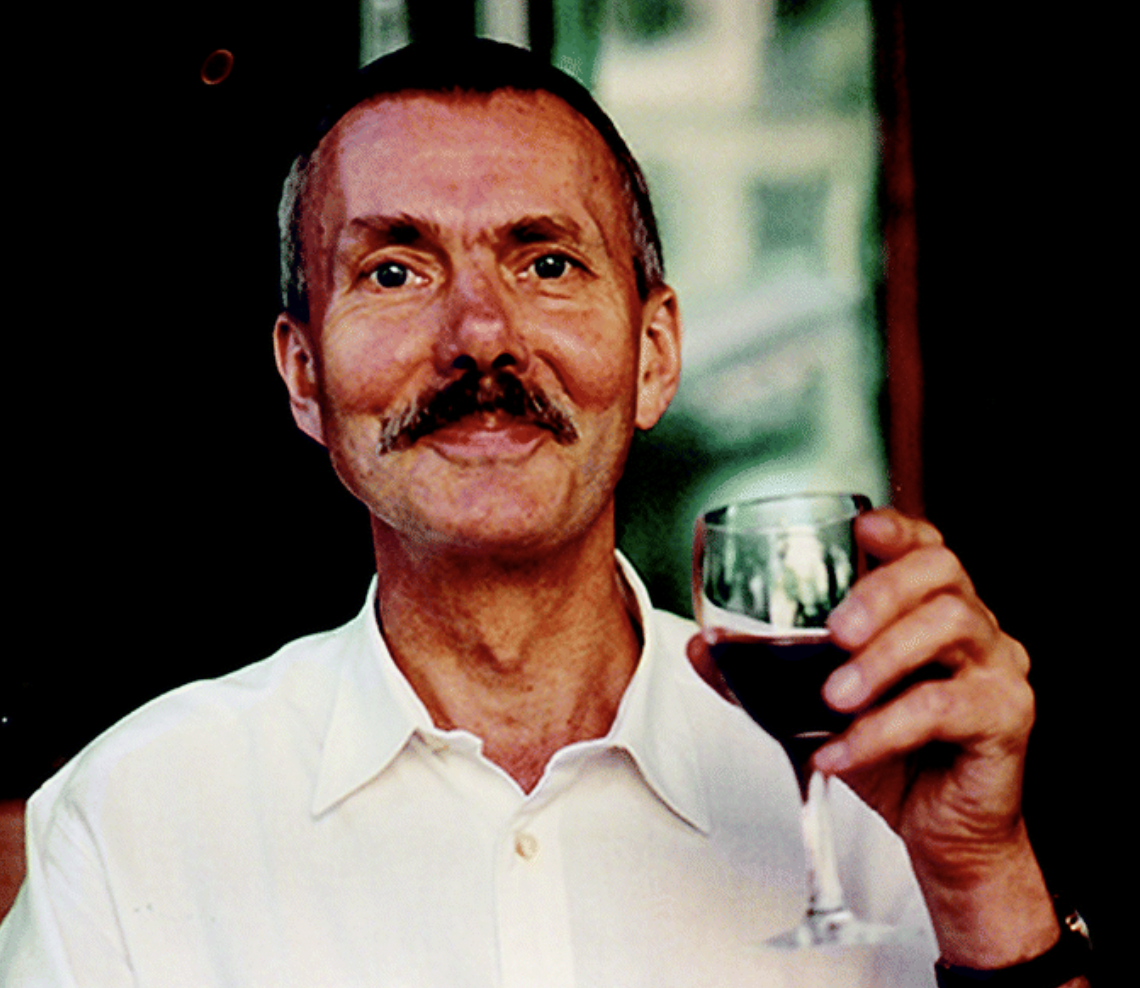

Eminent chemist and superhero of the organic chemistry textbook, the late Stuart Warren (1938-2020). Image courtesy of The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Yet buoyed up by my success in uncovering prejudice in the world of organic molecules, I penned everything down and chose to run it past my hard-nosed colleagues, expecting the inevitable snub. To my surprise, the first to read it was excited by my ingenuity and urged me to table it at the next departmental curriculum meeting. And so I did, and with some trepidation. This would surely be a test of how potent a spell of postmodern absurdity had enraptured my fellow scientists. Was I off-kilter or on point? Impossible to say, and only an experiment would reveal the truth of the matter. All scientists would recognize this methodological approach; and they would also identify the imperfection of the design. There was no control.

When it came to it, of the half-dozen or more attendees on the inevitable Zoom meeting, only one raised a critical voice. “I don’t like the Postmodernists, so I’d rather we didn’t teach it.” Or words to that effect.

What was the result? Was I the object of public ridicule? No. I was sent away to seek out a co-teacher in philosophy or social science to legitimate the proposal and offer to cross-list the course in other departments.

Later, I received a phone call. It was the professor who first read the syllabus, my advocate, the reason I had come this far. “David says you are trolling us. Are you trolling us?”

A short few days later, I filed a grievance against David. You see, the word “troll” is a slur in the gay community. It is a label for an older, less attractive man who cruises, as Wikipedia blithely puts it, “in a notably wanton manner, and with lessened standards of what one will accept in a partner”. I was disgusted and outraged.

My chair, who was notably female and woke, and presided over the cascading administrative fallout was forced to go on the record. “In my interview with David he made it clear that he was not aware of the alternative meaning of ‘troll’ as a homophobic slur.”

That’s too bad. As any social justice warrior will tell you, intent is irrelevant. It is how the victim is made to feel. Words have impact. Words are violence. Find your courage.

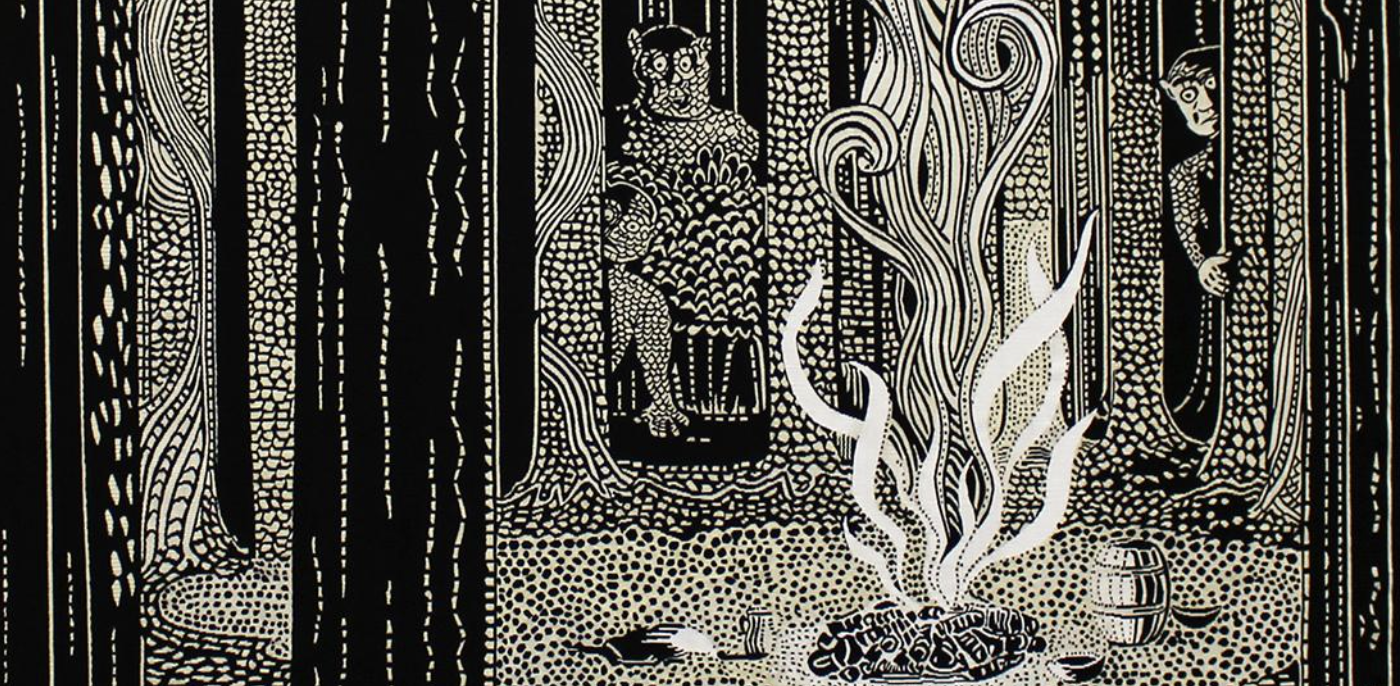

The Trolls. After an original illustration by J. R. R. Tolkien, 1937. Copyright The Tolkien Estate. Image courtesy of Cité internationale de la tapisserie, Aubusson.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.