André Ventura, head of the Chega party, which surged to tie with the Socialist Party as the second-largest force in the Portuguese parliament.

The steady rise of the populist right in Europe was confirmed this week by the results of elections held on May 18th in three different countries: Poland, Portugal and Romania. So too was the anti-democratic nature of the elite backlash against voters who increasingly threaten the establishment’s crumbling consensus.

In Poland, liberal Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski narrowly won the first round of the presidential election on Sunday against his right-wing rival Karol Nawrocki. Trzaskowski, the deputy head of Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform party, won 31.36% of the vote while Nawrocki, supported by the national conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, took 29.54%. Since neither of them topped the 50% needed to win outright, they will now face each other in a run-off on June 1st.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

At first glance, Trzaskowski’s widely expected victory in the first round might seem like good news for the center left. But despite appearances, the outcome was a political earthquake not only for Tusk and his party but for PiS as well. For one thing, the mayor’s margin of victory at a mere 1.7% was much smaller than predicted by pollsters, giving Nawrocki momentum heading into the second round. Also striking was the unexpectedly strong performance of other hard right candidates: Slawomir Mentzen of the Confederation Party came third with almost 15%, more than doubling the party’s share of the vote from the previous presidential and parliamentary elections, while fourth place went to Grzegorz Braun, a far right member of the European Parliament, who drew another 6.4%.

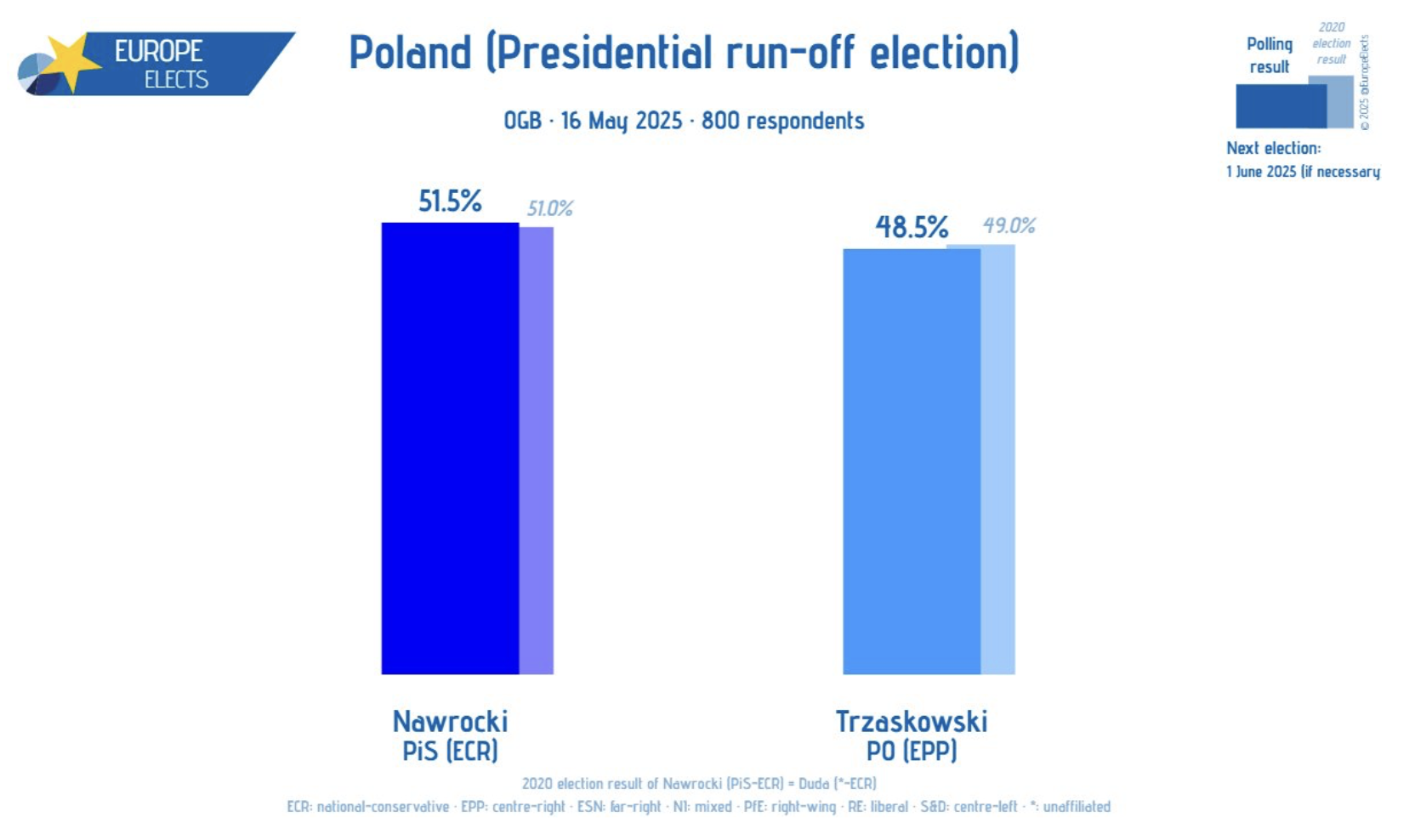

The competition between the two frontrunners will now be over who can attract more voters who opted for one of the minor candidates in the first round. This favours Mr Nawrocki, whose vote share combined with candidates to his right added up to nearly 52%. Parties that support the government did less well overall: Szymon Hołownia, speaker of parliament and leader of the center-right Poland 2050 party, took 4.99% while Magdalena Biejat of the Left won 4.23%. Adrian Zandberg of the far-left Together party, which is not part of the governing coalition, took an additional 4.86%.

Internecine disputes on the Polish right mean that many of PiS’s nationalist opponents may yet abstain for the run-off on 1 June. Much will hinge on supporters of the Confederation Party, a mostly young bunch of free marketeers and immigration restrictionists who have clashed with PiS over its statist ways in the past. But they have more in common with Law & Justice than with Mr Trzaskowski, who polls confirm is now in the weaker position going into the second round.

This result would be a major disappointment for Donald Tusk and his government. Since forming a coalition back in 2023, their agenda has since been repeatedly thwarted by incumbent right wing President Andrzej Duda, who has vetoed some two dozen bills designed to undo the preceding eight years of PiS’s Catholic conservative rule. With Trzaskowski in power, Tusk and his allies – an eclectic combination of leftists, greens, free marketeers, and conservatives – would finally be able to pass the judicial and institutional reforms that the EU has demanded for years — although reforming Poland’s restrictive abortion laws, a longtime liberal ambition, may still evade them.

But even if Trzaskowski is somehow able to attract enough centrist and left-wing votes to win, the first round result is proof that the battle for the future of Polish politics will largely be fought on right wing terrain. In response to mounting energy on the right, the ostensibly liberal candidate already had to run a campaign based on Poland First issues: he supported Tusk’s decision to suspend asylum rights along the border with Belarus, condemned the EU migration pact, and hinted at restrictions on the border with Germany to keep asylum seekers out. He also played down his support for LGBT issues and stressed his support for spending 5% of GDP on defence. With parliamentary elections in 2027, Trzaskowski and Tusk will have little room to retreat from these positions. A win for Nawrocki, meanwhile, would hamper Tusk’s agenda for the next two years and leave PiS to figure out how to prevent its voters from defecting rightwards towards Confederation. Either way, an increasingly nationalist Poland will move the EU’s center of gravity towards the right on migration and security in the years ahead.

In the second of the weekend’s elections – a snap parliamentary general election in Portugal – the ruling centre-right Democratic Alliance (AD) government was returned with around 32 per cent of the poll. But in a shock result, the national populist Chega party ran neck and neck in second place with the opposition Socialists. Both polled around 23%: the best result for the hard right in Portugal since the overthrow of the Salazar dictatorship half a century ago. Like its sister parties across the continent, Chega had campaigned against mass migration, soaring house prices on the back of it (which jumped another 9% last year), and the EU.

With all the votes counted, Prime Minister Luís Montenegro’s coalition won 89 seats in the country’s parliament, far fewer than the 116 needed for a governing majority. Pedro Nuno Santos’ Socialist Party was punished by voters for forcing elections that the public considered unnecessary, losing 20 seats and ending up with just 58 lawmakers in the parliament. That leaves it tied with Chega, which surged to secure the same number of seats.

The party’s latest performance confirms its rapid continuing rise, which has seen go from having just one lawmaker in parliament when it was founded in 2019 to becoming the third largest party in last year’s election — to now controlling a quarter of the seats in the country’s legislative body. Andre Ventura, Chega’s leader, a former trainee priest turned television sports commentator, declared: “We didn’t win these elections but we made history. The system of two-party rule in Portugal is over.”

The center right incumbent Prime Minister, Montenegro, has nonetheless refused to make any deals with Chega. This means his government will have to negotiate piecemeal parliamentary support from the center left unless he finds an alternative solution, and under the Portuguese constitution the earliest he could call a fresh national election is late spring of next year. In the meantime, his decision to emulate the policy of quarantining popular national conservative parties that has been adopted in Austria, Germany, and France even when they win the most or (as in this case) the second most seats or votes suggests the Portuguese elite would rather hobble along with a hamstrung minority administration than compromise with voters by adopting a tighter immigration policy.

Help Ensure our Survival

In Romania, the abrogation of democratic norms to defeat populism was more extreme. Last weekend’s election was the country’s second attempt at electing a new president, the first having been annulled at the last minute by the constitutional court back in December, after it was unexpectedly won by Calin Georgescu, another national populist. In justifying its extraordinary decision the court cited declassified intelligence which alleged Russian interference through Tik Tok videos, which was always a tenuous basis for overturning an election for reasons I explored here.

The onus has since been on country’s government to lay out sufficient evidence to substantiate this allegation, yet even the BBC’s ‘Global Disinformation Unit’ admitted last month that they “still haven’t provided any concrete evidence of Russian interference in the election, frustrating many Romanians”. When Georgescu soared in the polls ahead of this year’s rescheduled elections, which he was heavily favored to win, the authorities detained him before he could register to stand again and then banned him altogether. To make doubly sure that the ‘correct’ candidate would emerge victorious against his ally, the information ecosystem surrounding the new election was then deliberately manipulated: Pavel Durov, CEO of Telegram, testified publicly this week that French intelligence had approached him to suppress Romanian conservative voices ahead of the vote. Whilst he refused, it is possible that others did not.

George Simion, leader of the national populist Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), stepped in as Georgescu’s replacement. In addition to skepticism about EU climate policies, LGBT issues, non-EU immigration and continuing Romanian support for the war in Ukraine, he rode a wave of popular indignation at this brazen election interference by Romania’s political establishment as well as a sense that the country’s post-communist economic boom has stalled. These sufficed to carry him to victory in the first round of the rescheduled election held on May 4, when he secured nearly 41% of the vote. His nearest opponent, Nicușor Dan, the favored candidate of the EU and mayor of the capital Bucharest, received just 21%. Simion led by nearly double digits in pre-runoff polls. He seemed to have the momentum.

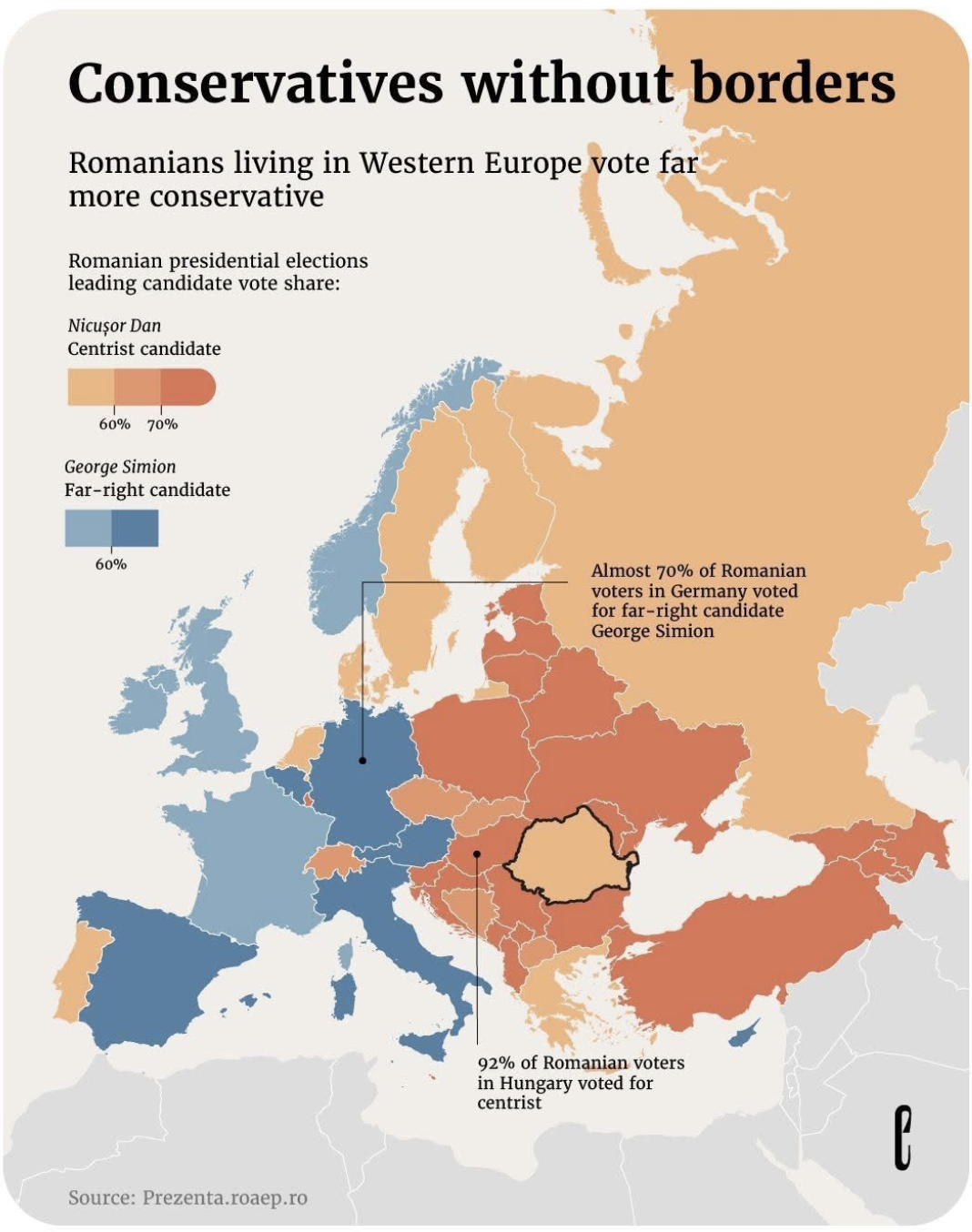

But in the second round vote last Sunday, Dan ultimately emerged victorious with 54% of the vote to Simion’s 46%. His recovery from a 20-point deficit to an 8-point win suggests that he won over most voters who had not backed Mr Simion in the first round, and the gap closed further after a televised debate which Mr Dan was widely agreed to have won. The turnout was a record high. The country’s large diaspora, with more than 4m citizens living abroad (compared with 19m inside the country), turned out in huge numbers. And unlike in the first round, they did not break as heavily for Mr Simion overall, although conspicuously those in Western Europe lent more strongly in the populist’s direction – something anecdotally attributed to their disillusionment at the effects of progressivism and mass immigration on countries like Britain, Germany and France, and an aversion to seeing the same happen back home.

If democracy had been allowed to run its course, the new President of Romania would in all likelihood be Calin Georgescu. He was the winner of the first round of the original presidential elections and was heavily favoured to win the second round too. But in the event, Romanian and EU elites got away with a judicial coup and subsequent campaign of election interference and censorship that, had it unfolded in Russia, would doubtless have been widely denounced in Brussels and mainstream media as a sham. As Vice President JD Vance noted in his Munich speech in February, you don’t have to support all or even any of Georgescu’s policies to recognise that their behaviour indicates a profoundly disturbingly unwillingness to allow democratic dissent against the current elite consensus.

Overall, the three elections last weekend therefore paint a mixed picture. On the one hand, in each country a dissatisfied electorate swung sharply to the right for change, and towards national conservatives rather than neoliberals — like it has across Europe. On the other hand, an increasingly unpopular progressive establishment continues to rely on techniques of managed democracy to maintain its faltering grip on power, whether by quarantining popular opposition parties in favour of minority governments, as in Portugal, or by invoking the spectre of Kremlin meddling to justify censorship and even overturning an election altogether, as in Romania. Yet despite their best efforts, the political wind that has been blowing strongly to the populist right in Europe for the past decade is not going to weaken any time soon, and seems more likely than not to sweep through Warsaw next in the presidential run-off on June 1st.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.