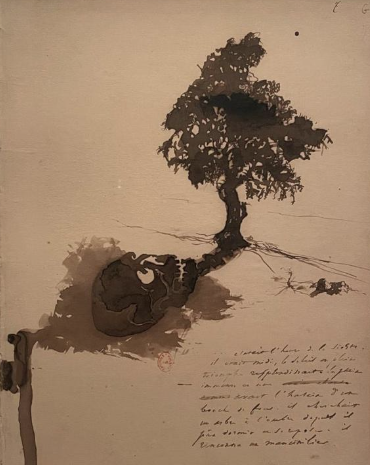

Nature can pull the most devilish of tricks. Trees promise shade in the sweltering midday sun, seeming to offer relief from “heat like the mouth of an oven”. Little beknown to the delirious wanderer, poison seeps from the bark, mobilized and deposited as toxic wash via the rain. Ingested, the Manchineel Tree is lethal; even sitting underneath it can cause skin to blister. Victor Hugo (1802-85) illuminates what danger lurks in the shadows in an illustration of 1856 that shows a human skull basking – face upwards – underneath. Comfort undergirded by baked death.

The Shade of the Manchineel Tree (Notes from a Trip to the Pyrenees and Spain) (1856)

What tempted Hugo towards this dark subject matter? This was a question I sought to explore as I moved through Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo (21 March – 29 June 2025) at the Royal Academy in London. Most known for his literary works – notably, Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame – Hugo produced thousands of sketches which enhance, but do not illustrate, his published texts. Intricate details from his travels were depicted on a miniscule scale, which concurrently inflated them via the act of preservation into something monumental and profound.

One of the most prophetic sketches is Mushroom (1850), a drawing made during a politically tumultuous period for Hugo. In keeping with the Manchineel Tree, Hugo prizes up a stone to reveal serpents lurking in nature’s underbelly. The mushroom shape foreshadows the haunting image of the nuclear bomb: mass destruction printed into common memory in the cookie-cutter shape of Marylin’s skirt blowing upwards. In Hugo’s sketch, a human face peers out from the crystal-ball stalk to warn about the real source of poison, destruction cultivated by human hands. The electric red and blue contrast against the tea-stain brown of the background to suggest a transition into ominous modernity; bright but acidic.

Mushroom (1850)

Deeper readings are constantly invited by Hugo. He conducted seances during his period of exile in Jersey (1852-55). Ink blots and accidental marks reveal the unconscious hand. Some drawings bleed spirits of the deceased. Architecture Renaissance (c.1847-50) is flat, dull, and in looking this way emits dead energy. Gothic arches and details shadow the underlife. Tache on Folded Paper, Retouched with a Pen (1850-57) evidences the unconscious, but finished with a pen to clarify the human faces and figures that make up the spine in the fold of the page. Fingerprint faces peer down in Ink-blackened Page with Half-moon and Fingerprints (1864-65). Although the orientation of this work was not prescribed by Hugo, the traditional hang of the work recreates what one could imagine at a burial. Whilst contemporary Gustave Courbet (1819-77) painted A Burial at Ornans (1849-50) to capture a funeral procession from the perspective of the foot of the grave, this work by Hugo places us in the bed of the deceased: deep underground, familiar faces lose form, as we fall to become ashes.

Given his macabre interest in hauntings, it is no surprise that Hugo had a lifelong fascination with castles. Some of these castles are imagined, others real. My favorite of these is The Town and Castle of Vianden by Moonlight (1871). A stenciled outline of a castle rises above a mist-filled landscape. We view this distant scene unfurl over the pencil-drawn higgledy-piggledy roof-tops. Scale-like tiles sink on sagging edges, whilst chimneys spike upwards from ski-slope panels. Their non-uniformity bears the hand of production; a human spirit, unflattened by Enlightenment rationalism.

The Town and Castle of Vianden by Moonlight (1871)

Hugo wondered not only under the ground, but also beneath the waves and upwards into space. Abstract compositions envisage the solar system. These seemingly divergent landscapes entwine and merge in the imagination. The Serpent (c.1856) is the most pertinent example. Writhing in a blackwashed background are the curves of a ferocious serpent, whose open mouth emits a lava breath. With wide disc-like eyes, the target of the fire is left ambiguous, but warns of the invisible monsters who lurk in waves and the imagination. He could be a monster taken from a Medieval map or a trick of the eye on a seafaring journey; lest we dare consider his reality.

References are occasionally made to his novels, but these are made in theme rather than illustration. The Bowels of Leviathan (1866) is the more enlightening of these through its chthonic subject matter. One recalls the sewers in Les Misérables: the underbelly of Paris, home to forces within that affect life on the surface. Similarly, shipwrecks – such as ‘The Durande’ Ship after Sinking (1864-66) – evidence the concealed vestiges of humanity; lost but not forgotten, ghostly imprints that seek to be discovered.

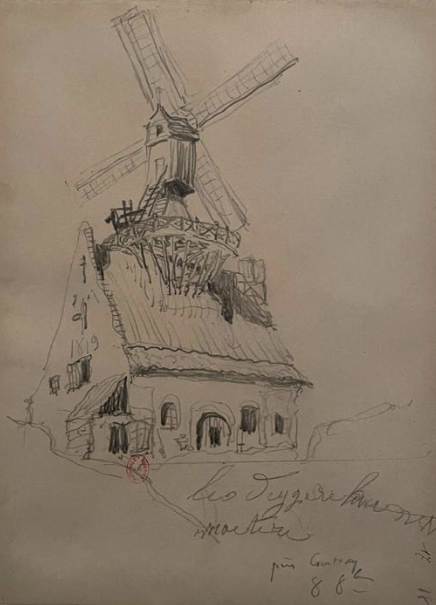

The fantastic isn’t necessarily dark. Windmill on the Roof of a Farmhouse near Courtray, 8 October 1864, depicts a windmill atop a farmhouse. Given his imagination, the verdict is the viewer’s as to whether the drawing is faithful. Really, it doesn’t matter, because the meaning is in the decision to capture the scene as a drawing. Shaky lines make the notion of a protruding windmill even more astounding. It rises as a flying machine from the roof of a dilapidated cottage. Man can imagine the extraordinary through technology. Childlike innocence in this image recalls the magic faraway tree. Not all imagination serves only to illuminate death.

Windmill on the Roof of a Farmhouse near Courtray (8 October 1864)

Despite the macabre themes, Hugo’s persistent faith in humanity is apparent throughout. During his own lifetime, he campaigned for the abolition of slavery and against capital punishment. The latter suggests a belief in the reconcilability of mankind. There are characters in literature that are redeemable and others who are not. What seems to be a constant in the work of contemporary Charles Dickens (1812-70), perhaps partly due to the complexity of his characters who refuse categorical conclusions, is that the reader urges each to be redeemed in the end. Imagination in the work of Hugo – for me, what constitutes the “astonishing things” as specified in the title – represents the unlimited potential of human good.

The drawings themselves are exceptionally precious and scarcely exhibited due to their sensitivity to light. This is even more reason to visit the exhibition before it ends. Like human life, the drawings are sacred and physically transformed by the passing of time. However, the imaginative weight of the drawings – ones that possess the potential to spark stories and associations in the viewer – is enough to touch human lives far beyond the material page.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.