Less than a year after achieving the biggest political breakthrough of his career, Geert Wilders has walked away from government in the Netherlands, collapsing the four-party coalition he was meant to lead. His resignation from the governing alliance, announced abruptly this week, has triggered yet another Dutch general election and very likely ended his brief and chaotic experiment in power.

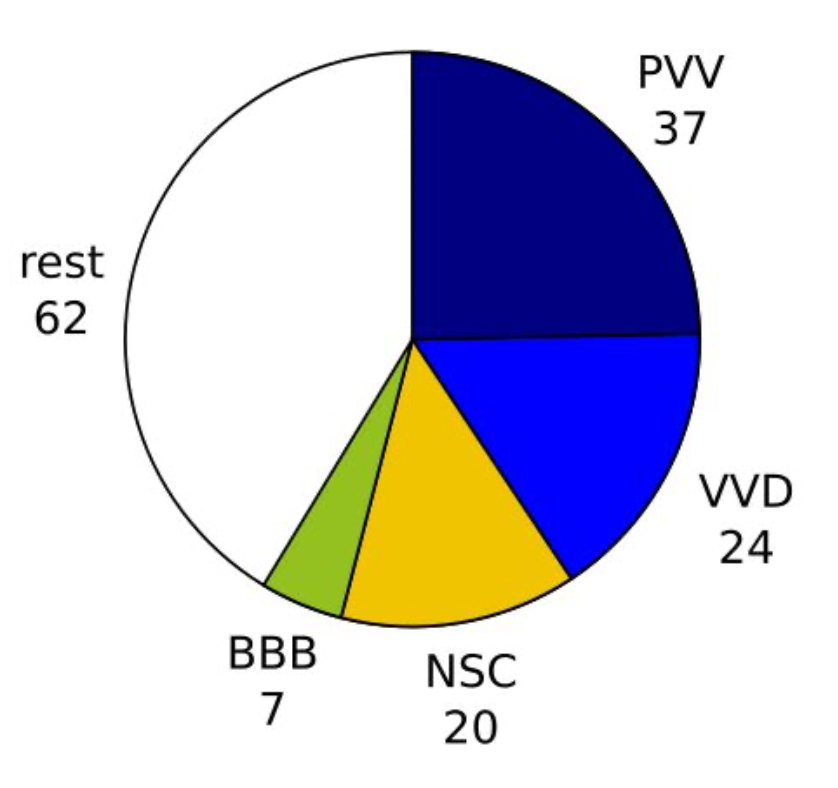

Dutch Parliament breakdown, with Wilders’ PVV taking the greatest share of seats.

This is not just a Dutch story. It holds a warning for those in Britain who hope that the future of conservatism lies in a realignment of the Right – a post-liberal alliance of reformers, populists and small-state traditionalists. That vision may well be possible, facilitated by the rise of Reform UK. But the collapse of the Wilders coalition shows how fragile such a project can be without discipline, clarity, and above all, honest upfront agreement on fundamental policy.

Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) won the largest number of seats in the Dutch parliament last November, capitalising on widespread dissatisfaction with immigration policy, housing shortages, and the perceived drift of the political elite. For a time, it seemed as though the Netherlands might become the first Western European country to see a long-term populist right party successfully enter government. But that prospect has now imploded – not because of sabotage by the Left, but because of dysfunction within the Right itself.

The official trigger for Wilders’ departure was migration. Frustrated by a lack of progress, he issued a unilateral ten-point asylum plan demanding military enforcement of border controls, the deportation of Syrian refugees, and a blanket end to family reunification. When his coalition partners – including the centre-right VVD, the agrarian-populist BBB (Farmer’s party), and the centrist New Social Contract (NSC) – refused to endorse it wholesale, Wilders quit.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

What is striking is that these proposals were not raised in the spirit of negotiation but rather were issued as ultimatums. There was no effort to forge consensus or engage in the usual rigmarole of continental coalition politics. His asylum minister, already struggling to manage her department, and under constant attack from coalition allies for attempting to push what have been deemed ‘unconstitutional’ policies, was also sidelined. Wilders demanded total compliance – and when he didn’t get it, he walked.

Asylum Minister, Marjolein Faber ahead of last Wednesday’s cabinet meeting.

This behaviour may well have destroyed his credibility as a national leader. Wilders, who had previously also withdrawn from a VVD minority government, appears to many to be temperamentally and politically unable to work within a political system shaped by proportional representation and depending on compromise. While comfortable in opposition – denouncing elites, defending the volk – he may have proved incapable of the patient work of governance. And after decades of political dissatisfaction, and ideological stagnation with the VVD, Dutch patience is wearing thin for politicians who can’t find a way to make good their commitments.

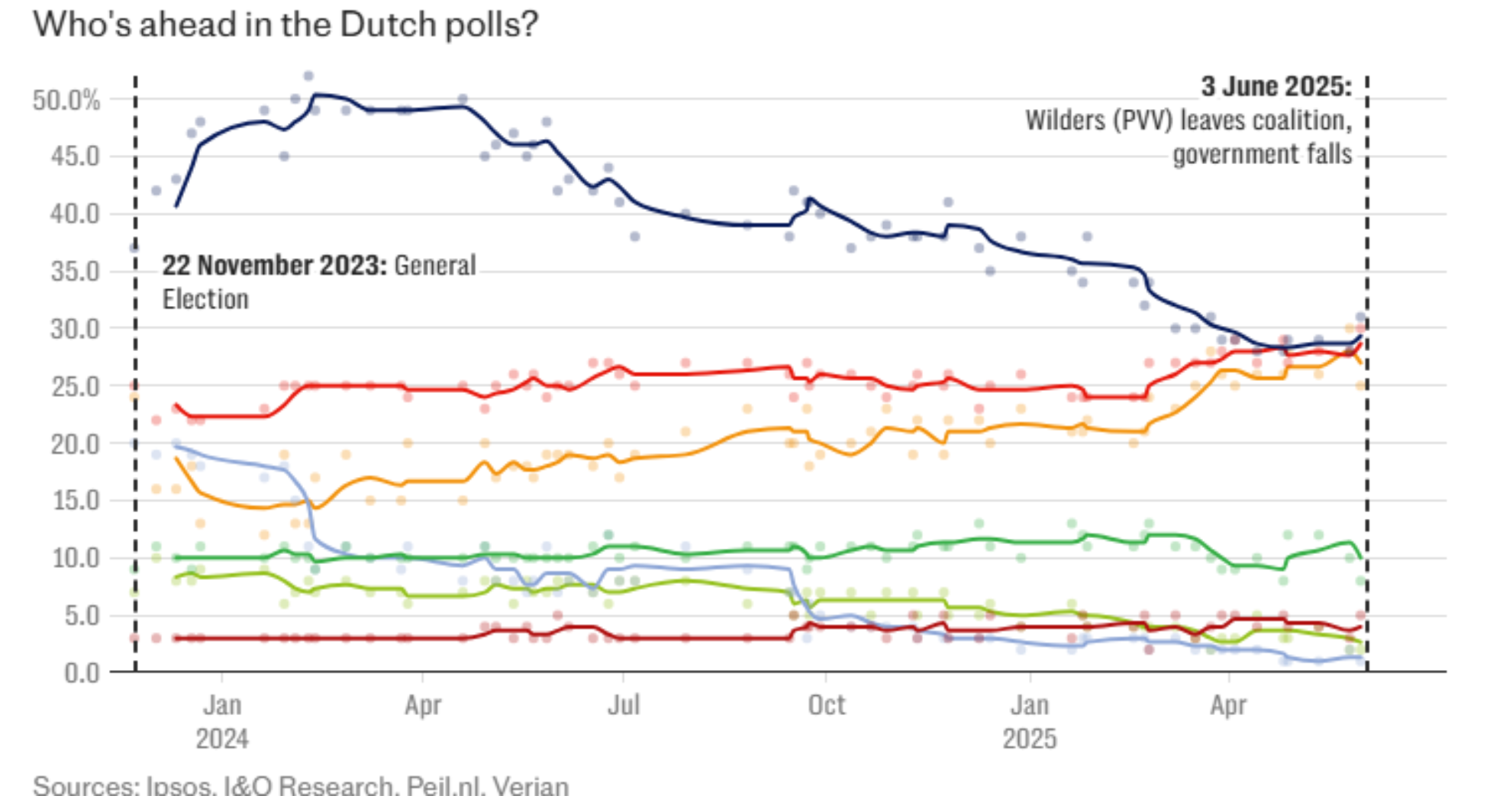

The collapse has left the Netherlands in limbo. Prime Minister Dick Schoof has resigned and will now serve in a caretaker capacity. Polling suggests that the PVV has lost the commanding lead it once held, and while Wilders still speaks optimistically of returning as prime minister, it is difficult (although not impossible) to see a path back to power. Most of his potential allies have declared they will not work with him again. As one coalition partner, Caroline Van der Plas (BBB) put it, this was “a kamikaze act” – reckless and self-defeating.

But the cracks were already growing within the coalition before Wilders issued his ultimatum and there is an unlikely chance, but a chance nonetheless, that Wilders manages to pull off a stroke of political mastery. The more extreme measures which Wilders and Asylum Minister, Marjolein Faber, were hoping to push through to tackle the housing crisis and to halt asylum have been held up at every stage. After Nicolien van Vroonhoven, leader of the centre-right NSC party, said she was unwilling to renegotiate the coalition agreement, Faber accused her of “living in a paper reality”. Attempting to persevere in government while entirely failing to deliver on the policies promised to an increasingly radicalised voter base would be a death sentence for Wilders’ party. It would evince the sense of the betrayal felt by British voters at the last Conservative government, for which they were punished severely.

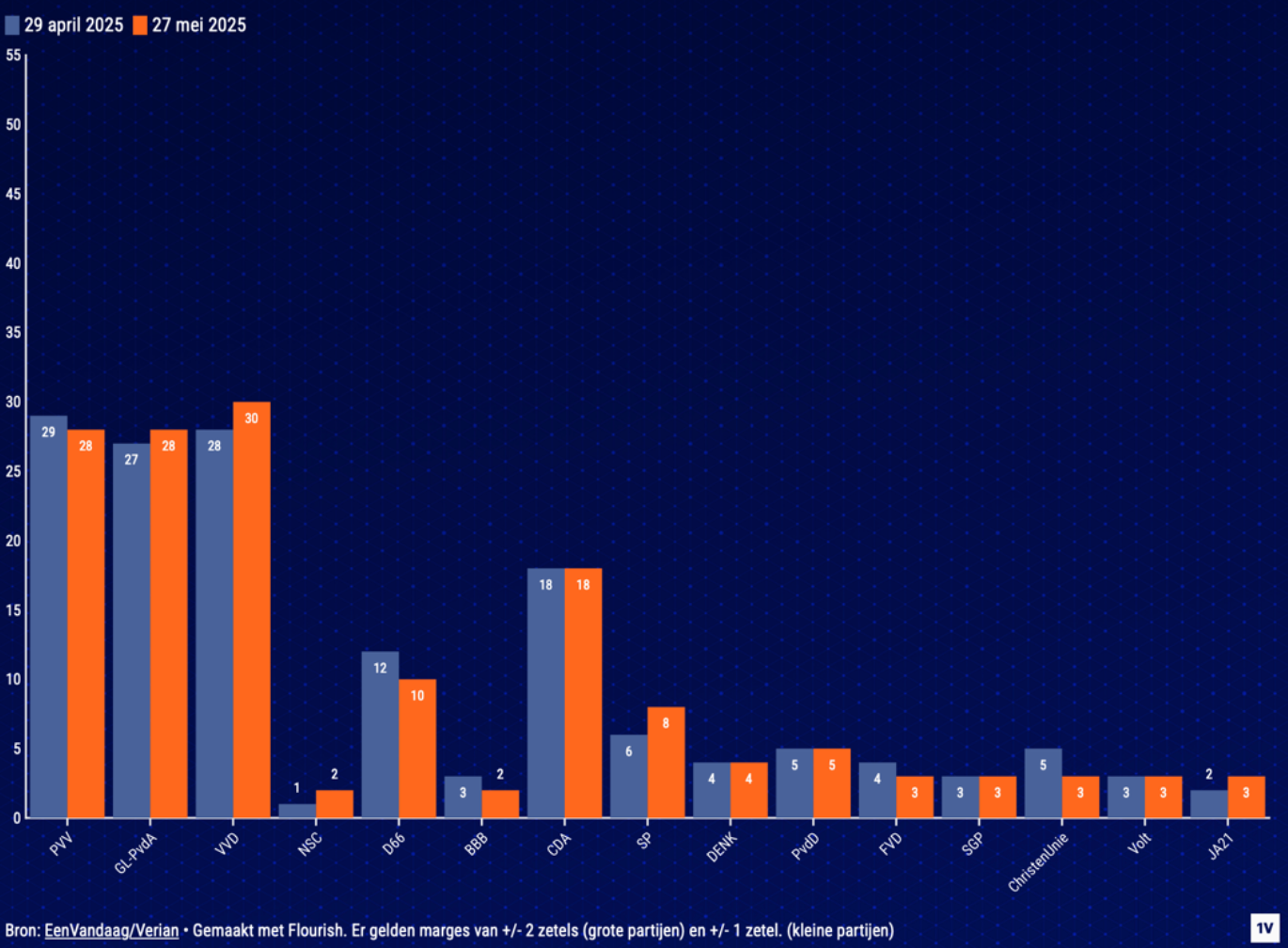

Popularity of the governing parties between April and May. Source.

If Wilders can convince the Dutch that the coalition parties have made it impossible to deliver on his popular migration policies, and that they will always do so, then perhaps he can drive the electorate to lend him their vote in one last push to achieve political dominance. If his party re-enters government in Autumn with a vastly greater share of seats, even if shy of a majority, with increased bargaining power, the political calculations of the right-of-centre parties would have to change. He was probably right to leave the coalition but was wrong to enter into coalition without carefully and confidently drawn red lines over the delivery of the PVV’s pillar policies.

There is, for Britain, a serious lesson here. On the Right, there is a growing recognition that the post-Cameron Conservative Party has failed to consolidate the working-class realignment it began in 2016. Many look to figures like Nigel Farage and to Reform UK as potential coalition partners in a new political alignment. Others imagine a broader bloc of socially conservative, economically reformist voices bringing the Red Wall and the Tory shires together. But any such arrangement will fail unless it learns from the Dutch example.

A successful coalition requires shared purpose and must be governed by politicians with a firm but cool temperament. Red lines must be drawn clearly and agreed early. If a party wins the largest share of the vote but finds itself unable to deliver on its central promises – whether on immigration, housing, net zero, or issues of national sovereignty and cooperation with international institutions – the electorate will punish it severely. Protest politics has its place, but government requires discipline. Without it, there is no delivery, only drift and disillusionment.

Help Ensure our Survival

Wilders’ failure also illustrates a deeper point. Many populist parties are defined by a politics of opposition. Their strength lies in voicing grievances, not in crafting solutions. That is can be a necessary role, especially when decades of political consensus, for example the elite belief in the fundamental virtue of mass immigration, has drawn them ever further from the mood of the country at large. But if they are to govern and govern seriously, they must move from protest to policy. That means Reform UK or any other party hoping to exploit the realignment and gain political dominance must focus on professionalising, building capable teams, and showing that they can govern not only with passion but with competence.

Britain may yet see a reconfigured Right – one that blends cultural conservatism with economic realism and democratic accountability. But it will only succeed if those who lead it are prepared to govern seriously. That means avoiding the Wilders temptation: to win votes on bold rhetoric and then collapse when the difficult work of governing begins.

The Dutch public may have wanted change, but what they got was dysfunction and unworkable policies. If Britain is to avoid the same fate, parties on the right would do well to remember that there are certain questions on which the public will not take no for an answer. No party should enter a coalition unless they are sure they will be able to deliver on these.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.