I’ve attended a fair number of feminist conferences and exhibitions in my time. Most of them brandish the word “radical” in their title, as if to indicate significance. Women Create! – a two-day conference and exhibition platforming cancelled and at-risk female and feminist artists in London – did not pull this trick, but its radicality was inherent in its purpose and execution.

As a university student, I was often relayed feminist musings about past activist happenings. These anecdotes were packaged in shiny exhibition narratives at national and publicly funded institutions, such as the Tate Britain, which made them fashionable and, to an extent, mainstream. Women Create! was different. Firstly, founder Victoria Gugenheim contacted 300 venues who refused to stage the event. It was only with the Maya Forstater case in 2021 that the selected venue was then forced into agreement, given the ruling that employers must protect gender-critical beliefs.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

What makes Women Create! so controversial?

Gugenheim is unapologetic about her gender critical views. Her vision for Women Create! is simple: “Worldwide, women are having their rights to self expression censored, throttled and cancelled under growing tyranny. We’re here to change that.” The ethos underpins the selection of cancelled speakers and “politically incorrect” content that followed.

The conference itself was rough around the edges. Having arrived during the specified registration period, the panicked atmosphere and unfinished stalls made it immediately clear that the space was not ready. To me, this didn’t matter, and if anything proved its extra-institutionalized nature. Used to bureaucratic committees, I was intrigued by the teased unpredictability.

My attendance was motivated by the focus on creativity, as promised in the title and presence of ceramicist Claudia Clare in curating the main exhibition. Creativity was woven in spurts across the day and throughout the venue. Downstairs, mini displays – many of which were put together by the speakers – felt slapdash. Upstairs, Clare had curated a larger exhibition, complete with labels, for which she gave a programmed tour.

The curatorial narrative was straightforward: female artists who had either been cancelled or were at risk of being cancelled. Clare usefully began her tour with a description of what it means to be cancelled: the loss of exhibition, teaching, and lecture opportunities, and broken contracts, many times without explanation. These example criteria were useful given the denial by some commentators about the very existence of cancel culture.

Forty-eight artists were represented in the exhibition space. Many of their works developed the main themes of the speeches, overall helping me to grasp the array of sometimes complex and contradictory messages.

One theme of the conference was the erasure of so-called “butch lesbians”. This is the idea that masculine lesbians in their twenties today are falsely misled to believe that they are transgender. Mislabeling of historic figures as transgender (rather than homosexual) is an issue highlighted by artist Rachel Ara (b.1965). Her banner that reads “Lesbian Liberation Front D’Jèrri” represents her group that advocates for lesbian autonomy on the island of Jersey, where she was born and lives.

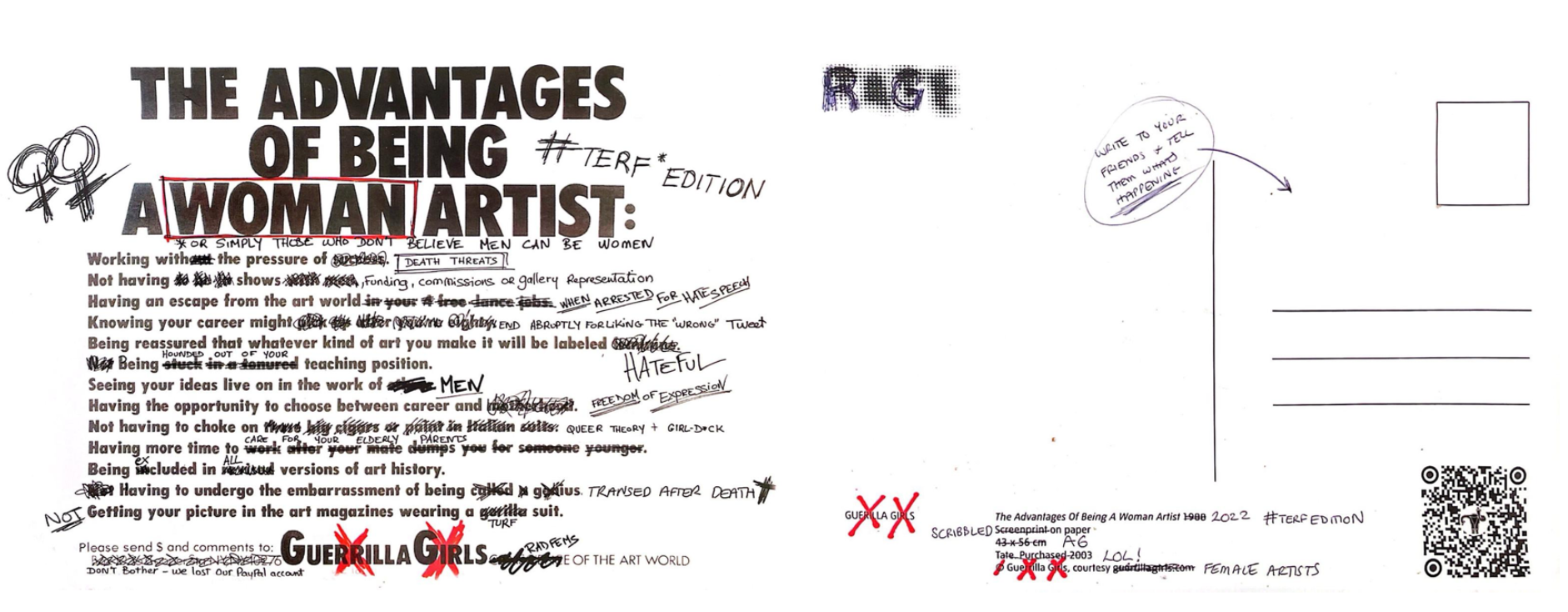

The target of Rachel’s campaign is Jersey Heritage’s erasure of the terms “lesbian”, “she”, and “her” to refer to the gay artists Claude Cahun (1894-1954) and Marcel Moore (1892-1972) in an attempt to rebrand them as “queer”, rather than recognizing their sex-based reality. Rachel’s playful artistic language successfully elicits warm feelings of humor about a serious subject, thereby challenging the mischaracterization of gender critical feminists as evil. One character on her flag work holds a sprig of kelp in an activist stance. Despite her shyness when describing the works – potentially a nervous hangover from previous political backlash – she admits her cheeky distribution of the TERF version of the Guerrilla Girls’ The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1988) to replace the postcards on sale at Tate Modern. The original list of sarcastic statements that highlight discrimination against women artists is reframed from the perspective of what so-called TERFs face today. For example, the final word in the original “Being reassured that whatever kind of art you make it will be labeled feminine” is replaced with “hateful”, and “Having the opportunity to choose between career and motherhood” is edited to replace the final three words with “freedom of expression”. Ara encouraged tour attendees to take wads of the postcards (freely available in the exhibition space) in order to do the same.

Another major issue explored in the conference and exhibition was Islamic policies towards women. Speakers on the first panel – Ibtissame Betty Lachgar, Jenny Wenhammar, and Maryam Namazie – discussed their own activist approaches. The most effective artistic exploration was not by a panelist, but by the ex-Muslim, Shabbana. In contrast to the fierce oratorical approach of Wenhammar – who took to shouting and swearing, in an effort “to take up space” – Shabbana was reserved, reflecting her completely different approach to awareness-raising. Her four untitled works of 2025 were visually striking because of the beauty she recognized in Islamic design. She used this stylistic language in order to present verses pulled directly from the Qu’ran, cursively handwritten in the billowing skirts of Whirling Dervishes. The harmony of the patterns and seemingly peaceful dancing figures entice the viewer to examine the texts. One skirt reads, “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women – admonish who disobey, do not sleep with them and beat.” Another, “When opportunity arises kill the infidels when ever you see them”. The violence of Islam speaks for itself in this striking act of subversion.

Messages about the erasure of butch lesbians and criticism of Islam were straightforward. The more complex issues explored in the conference concerned attitudes towards the sex industry, including associated aesthetic considerations about how women appear in culture and society. Claudia Clare’s wonderful hand-painted ceramic works explored these issues. Her Map of the Global Sex Trade (2022) is a satirical work that imagines a world in which the government becomes a pimp through the decriminalization of the sex trade.

What’ is intelligent about these maps is that they satirically pastiche trendy decolonial cartographies. These artworks – inspired by progressive discourses – engage with map iconography in order to highlight Western practices of empire-building. By drawing parallels between the slave trade and current calls for the decriminalization of sex work, Clare warns about a comparative current violence. However, and unlike decolonial activism, the sex industry is still supported as a “progressive” venture.

The world map contains seemingly innocent writing that spells out common lies about the industry. Presented against pistachio green land and baby blue waves, one banner reads “Land of milk and honey”. Through the insidious effect of these sugar-coated works, Clare warns that the sex industry is another form of slavery. She addresses this issue is a more confrontational way in The Humane Thing (2022). Casting any doubt aside, the plate directly addresses the economic argument in support of sites such as OnlyFans, stating the words of Irish sex-trade survivor Rachel Moran: “If a woman is hungry the humane thing to put in her mouth is food. Not your cock.”

These ceramics were internally consistent, but confusion arose when speakers critiqued the pornification of women and wider society. Some speakers concurrently said that we mustn’t judge women for what they wear – it’s their decision to wear short skirts and lipstick – but also critiqued a certain aesthetic stereotype described via hair color and body type, labelled as a “bimbo”. Moreover, there was concern about the use of make-up for reasons of pornification, rather than self-expression. Call me a cynic, but I do not believe that the two can be extrapolated. Self-expression is ultimately a public mask to be worn on a social stage that both men and women consume.

The most refreshing attitude and contribution to this debate was the performance by Nehanda Music. Fiercely articulate and charismatic, she admitted to wearing short skirts and flashing her cleavage to direct attention towards herself as a performer and the feminist messages contained within her lyrics. Cognizant of the fact that humans are aesthetic creatures, Nehanda Music’s approach promises to bring people together through skill and image, rather than provoke polarization.

Attention was perhaps the buzzword of the conference. Some speakers garnered for attention with bright hair colors and provocative artworks and methods. These were extreme in some cases, reliant on how controversy thrives on modernity and the shock of the new. In this regard, it was conversely refreshing to appreciate the homespun nature of Jenny Reilly’s suffragette-like banners, which contained statements such as “Lesbians’ sexual orientation is exclusive of men” and “The rights of women merit some attention”. These textile works reworked existing iconography to highlight how seemingly common-sense opinions about biological sex are now considered to be as radical as first-wave feminist principles. Wholesome and humble, but politically controversial in a tongue-tied society.

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.