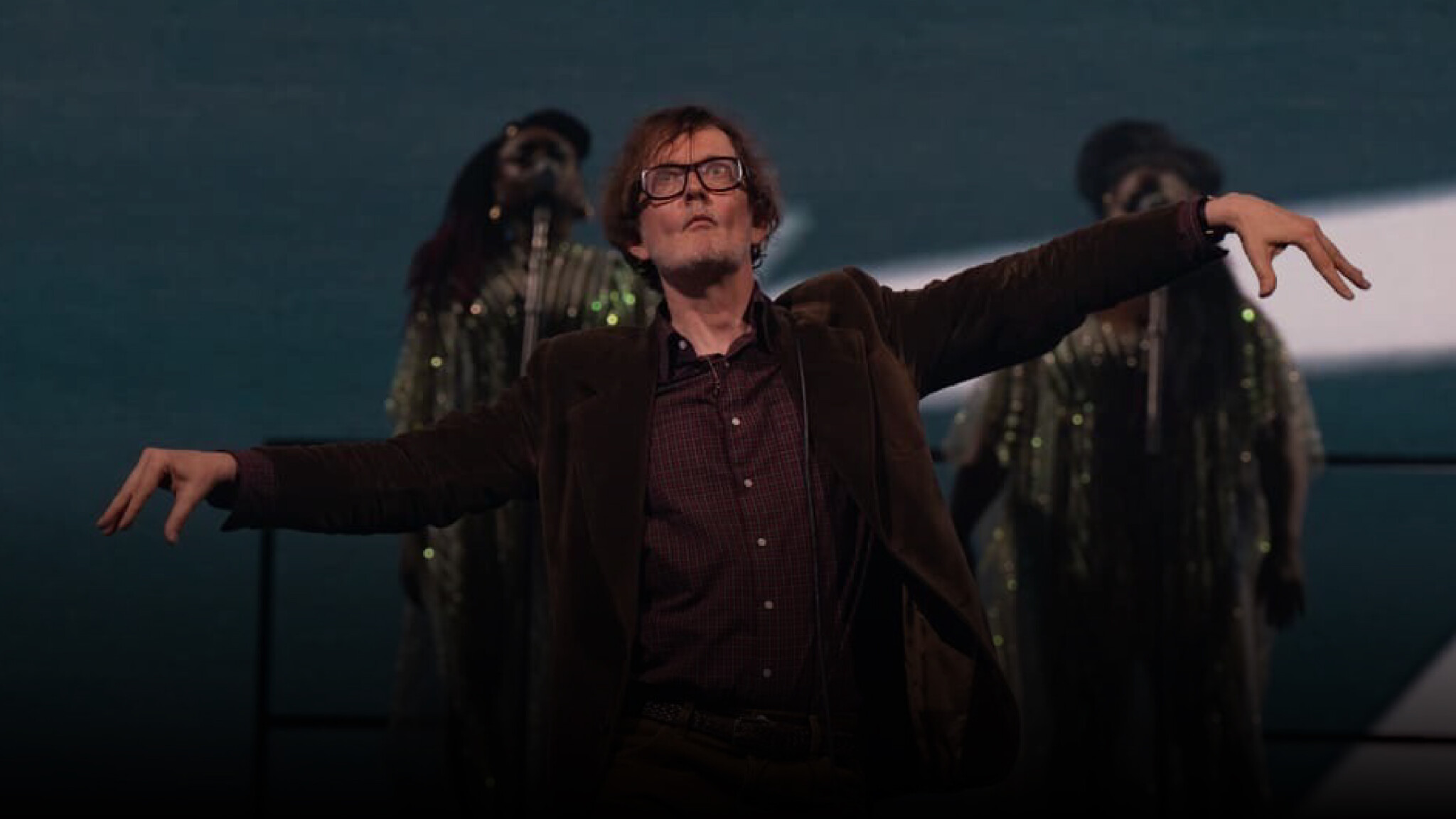

Jarvis Cocker returns with Pulp’s first single in 24 years—reviving more than music. Can he help reignite the soul of a culturally adrift Britain?

Spike Island, the first single from Pulp’s first album in 24 years, hits hard. It’s not just a return for the band. It’s a return of something Britain has been missing for far too long. In cultural terms, it’s a form of revivalism; the deliberate reclaiming of traditions, identity, and creative spirit in response to a perceived cultural decline. Revivalism is all about restoring what once made a culture distinct and influential; it has always emerged when societies sense they are losing something vital. And today, Britain is ripe for exactly that kind of reckoning.

The song is restlessly sly. The syncopated guitar riffs, understated bassline, and Jarvis Cocker’s unmistakable semi-spoken vocal style create an urgent, all-consuming energy. The song’s structure rejects the simple verse-chorus-verse pop formula, instead unfolding like a short story — a hallmark of Pulp’s finest work. It’s everything that once made the band essential, and, by extension, everything that made 90s Britain electric.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

It was a period when the nation’s music, film, and television were not only entertaining but also utterly dominant. Today, culturally speaking, Britain looks almost unrecognizable. In the 1990s, it was manic, magical, and unmistakably its own. Today, it’s…well, what is it? A nation more comfortable mimicking American trends than asserting its own voice. In 2025, Britain feels culturally adrift — unsure of itself and uncertain about what it wants to express. A once-fearlessly distinctive culture — working-class, middle-class, immigrant, outsider — has nearly vanished.

In the 90s, the British bulldog had bark and bite. From Tokyo to Toronto, British music resonated in a way not seen since the 60s. Oasis, Blur, Radiohead, The Verve — all different, all brilliant, all unmistakably British. From the anthems of (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? to the beautiful alienation of OK Computer, Britain wasn’t following trends. It was too busy setting them. Pulp captured British life with unmatched wit and edge, putting council estates, class envy, and kitchen-sink heartbreak into lyrics that entire generations instantly recognize.

Of course, the cultural wave didn’t begin and end with music.

In that delightful decade, British cinema was a thing of beauty. Four Weddings and a Funeral, Trainspotting, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, The Full Monty, Notting Hill — I could go on. Directors such as Danny Boyle, Guy Ritchie, and Mike Leigh took distinctively British stories and styles to the world stage, blending harsh environments, humor, and social commentary in thrilling new ways. Their artistic offerings captured something raw, smart, and daring that Hollywood could never manufacture. They launched a wave of British talent onto the world stage, including the likes of Hugh Grant, Ewan McGregor, and Kate Winslet.

British television thrived, too. Absolutely Fabulous, Father Ted, The Royle Family, Cold Feet — shows that weren’t afraid to be odd, rough-edged, or deeply real. Father Ted, famously rejected at first by Irish networks, was embraced by Channel 4 and became a cult classic across Britain and beyond. These shows crossed class divides. Whether you were an Essex lad or a Geordie girl, it didn’t matter. Great television belonged to everyone. It was television for all the people, not just some of the people. Today, Britain is many things, but cool isn’t one of them. As Stuart Hall observed in his work on cultural identity, national culture isn’t fixed; it’s constantly reshaped through creative expression. This was something Britain mastered in the 90s, and something it struggles to summon today.

Help Ensure our Survival

In 2025, British music exports are mostly nostalgia tours or algorithm-chasing indie acts. The film industry leans heavily on period dramas and Netflix co-productions that rarely resonate internationally. In many ways, Netflix’s binge culture has killed the old idea of tuning in weekly to catch the latest British show. Appointment television — the kind that made Father Ted or Cold Feet feel like shared national events — is all but dead. Now, we have Gogglebox, a show where the big idea is watching other people watch TV. It’s laziness masquerading as entertainment, a perfect symbol of a culture that has traded pure creativity for passive consumption.

Pulp’s return matters because it points both backward and forward. It reminds audiences that Britain didn’t dominate by being cautious. It led because the culture had something to say — and said it with the arrogance of Liam Gallagher and the charm of Jarvis Cocker. Pulp’s lead man never wrote for algorithms. He wrote for those who felt stuck in a dead-end town or wasting away in a terrible relationship. Radiohead built emotional worlds, albums that demanded attention and changed the way people thought about music. Even British pop exports like the Spice Girls and Take That, for all their manufactured cheesiness, felt part of something bigger. They were the faces of a nation bursting with energy. They were cultural foot soldiers, armed with pigtails and bubblegum, ready to unload earworms on the world.

The power of music, films, and TV isn’t trivial. Cultural dominance builds soft power. It projects an image of a nation’s spirit, talent, and aspirations. It creates a sort of global loyalty that no trade deal or military alliance can match.

Most importantly, 90s culture gave Britain a shared language. No doubt there’s still talent in Britain — brilliant bands, filmmakers, writers — still grinding away. But the system has shifted. Risk-taking has been replaced by risk aversion, and genuine artistic voices have been sidelined, even ignored.

Audiences want real bands, real stories, and real voices with relatable stories. Ed Sheeran seems like a lovely lad, but does he really have anything interesting to say? The people want another moment like the early 90’s, when a scruffy group from Sheffield could tear the house down with songs about common people and delusional dreams. They want another Trainspotting, a film that looks ugliness in the eye and finds a strange sort of beauty. They want music and movies that unite generations, not divide them into marketing segments.

Of course, Pulp’s return cannot fix Britain’s cultural decline alone. It can, however, remind everyone that an Icarus-like fall isn’t inevitable. British culture still has a heartbeat. But it’s fading fast. Does anyone have the courage, capability, or creative nous to shock it back to life?

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.