Last Wednesday, Victoria’s Secret hosted its second fashion show after a multi-year hiatus. Supermodels such as Candice Swanepoel, Doutzen Kroes, and Grace Elizabeth graced the runway once again, joined by a mix of both newcomers and fellow veterans. The wings were back, but for many fans the twinkle of the golden era was still missing, replaced by an emphasis on diversity that diluted the aspirational fantasy that once made it legendary.

Pictured above: Victoria’s Secret Angels pose together during the Snow Angels segment of 2013’s runway show.

Traditionally held during the run-up to Christmas, and inspiring many wish lists, the show once served as a debutante ball for the next generation of supermodels. The brand’s DNA – glamour, fantasy, and unapologetic sex appeal – was central to its worldwide allure. I first started watching the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show at fifteen, captivated by its spectacle: the beautiful ensembles, the live performances, the intricate styling, and, above all, the unshakable confidence of its models. Years later, when I finally had a disposable income, that sense of admiration naturally turned into loyalty; Victoria’s Secret became one of my favourite brands. By then, a new generation of Angels – Elsa Hosk, Taylor Hill, and Romee Strijd among them – had taken centre stage, and it felt as though the brand’s golden era was only just beginning.

“I will always cherish the Victoria’s Secret days. There was a kind of magic and discipline to it that’s rare in fashion today.” – Elsa Hosk, Vogue Scandinavia, 2021

However, as the progressive mist was settling over the West in 2018, fashion giants came under immense pressure to cast a more diverse array of models, and Victoria’s Secret was no exception. The brand was effectively forced to cancel its famous fashion show in 2019 after then-Chief Marketing Officer Ed Razek stated he had no intention of including transgender or plus-size models, claiming the shows were designed to capture a “fantasy”. He later apologised, but ultimately resigned. In the years that followed, Victoria’s Secret attempted to reinvent itself. It retired its iconic Angels in 2021 – once the faces of its most famous campaigns – and shifted toward new initiatives such as The Tour ’23, a digitally-focused showcase featuring transgender and plus-size models, athletes, and celebrities.

Pictured above: Attendees at Victoria’s Secret’s premiere of The Tour ’23.

For the Angels themselves, the downfall was disheartening. Models who had spent years building their careers around the brand’s once-celebrated image suddenly found themselves dismissed as symbols of an outdated trend. Contracts were ended, photo campaigns disappeared, and the annual show that had propelled so many of their careers was gone overnight. The most ironic part? The women who once inspired millions – many having come from humble beginnings – were now being erased in the name of empowerment.

This strategic pivot also came at a significant cost. Many long-time consumers criticised the rebrand as performative and inauthentic, while the brand’s signature fantasy-driven image was destroyed. Financially, the results were stark: net sales fell from $7.5 billion in 2012 during its golden, pre-progressive era to $6.78 billion in 2021, and further to $6.18 billion by 2023. This devastating decline showed that abandoning the core elements that originally defined Victoria’s Secret’s aspirational brand disappointed loyal customers without sufficiently attracting new ones.

Then, in 2024, its once-famous fashion show returned. Featuring some of the supermodels who previously stood as the brand’s Angels, such as Candice Swanepoel, and bringing back nostalgic elements like the dramatic feathered wings and elaborate runway staging, the twinkle was still sadly absent. It remained a far cry from the spectacle that graced our screens over ten years ago. Were the body types it featured broadly inclusive? No, but these models were called Angels for a reason. The show was designed to be a fantasy, showcasing women who trained like racehorses to strut down a long runway in wings that could weigh 20 – 30 pounds, all while posing perfectly for the camera.

Some of the models featured in last year’s Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show.

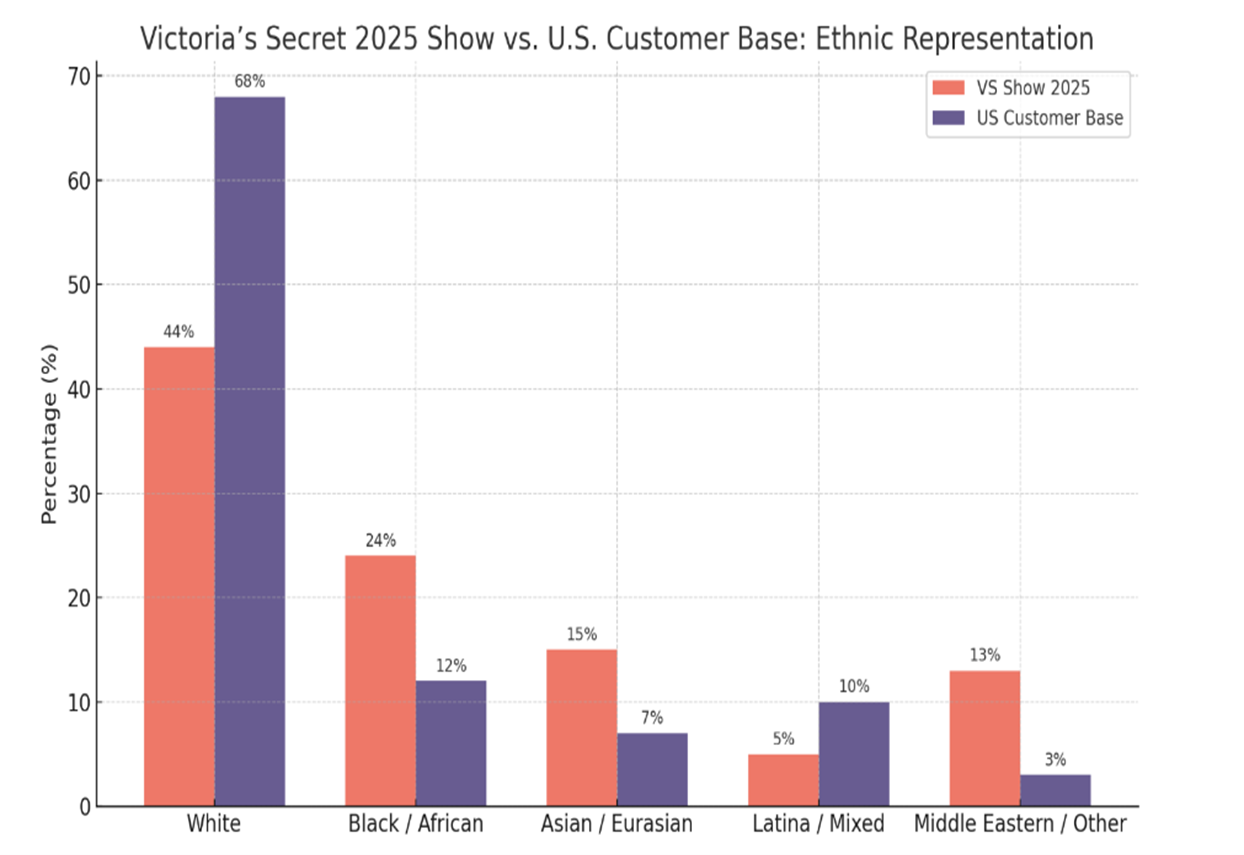

So, when loyal customers awaited photos from this week’s show, many hoped to be pleasantly surprised; perhaps this time it would feel like 2010 again, with no hollow virtue signalling, no hidden messages to ponder, and maybe even a diamond encrusted Fantasy Bra. And yes, while many of the Angel-era models reappeared, such as Doutzen Kroes and Grace Elizabeth, there was still over and underrepresentation; a tell-tale sign that diversity may be more performative than genuine.

Please note: Percentages are approximate and based on publicly available demographic and casting data; variations between sources may exist, but overall patterns remain consistent.

As I have argued in my other essays, if a brand is going to tinker with its fragile DNA in order to inject diversity, it should at least do so thoughtfully and authentically. Victoria’s Secret’s attempt, by contrast, has rightly been criticised as performative, as the graph above illustrates. White and Latina customers were underrepresented, while Black and Asian models appear at roughly twice the proportion of their real-world customer base.

Victoria’s Secret’s journey over the past several years serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of tampering with a brand’s core identity. In the late 2010s, a progressive mist drifted through the corridors of every major fashion brand. But now, that mist is beginning to lift. Perhaps, at last, the twinkling “Angel era” can be released from its gilded cage of progressivism, and step once more into the light. After all, millions of loyal customers would celebrate such a return.

Emily Fox is the Creative Manager at Uncommon Sense.

Help Ensure our Survival

Comments (0)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.