Elon Musk, who declared that only the AfD can save Germany, addressing the party’s conference in Halle

German voters go to the polls for elections to their federal parliament this Sunday (23rd February). Unlike the US, these are by far the most important national elections, since they will determine who will actually run the country as Chancellor (the German presidency, by contrast, is a largely ceremonial position). They are being held several months ahead of schedule after the premature collapse last November of the deeply unloved governing ‘traffic light coalition’, so-called after the three parties involved: the ‘red’ Social Democrats of outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz, the ‘yellow’ pro-business FDP, and the Greens. This three party arrangement, always unsteady due to ideological differences, finally fell apart when the FDP withdrew its support over disputes about the government budget.

Enjoy independent, ad-free journalism - delivered to your inbox each week

As the campaign to succeed it comes to a close, the German political establishment is panicking.

Despite years of smear campaigns accusing it of being ‘far right’, being surveilled by the domestic security service, and the support of over 100 legislators for banning it altogether, the national populist AfD is now more popular than ever; in the latest opinion polls, it is getting around 21 or 22 percent of the vote, second only to the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) & its Bavarian sister party the CSU, which can together expect about 29 percent. This puts it comfortably ahead of the governing Social Democrats (SPD), who are forecast to have their worst ever result with just 16% support, as well as the Greens on 13%. The AfD is polling particularly well with the zoomers, the youngest cohort of voters, who propelled its historic gains in EU parliamentary elections last June, and in the former East German states, where it is likely they will win every state.

Due to the German electoral system, even 45% could be enough to have a majority in parliament, which means that the likely next Chancellor, CDU leader and ex-Blackrock manager Friedrich Merz, will have to negotiate a formal or informal coalition to govern. He has already ruled out an alliance with the AfD, in keeping with the longstanding ‘firewall’ against co-operation with the hard right, so this means entering into an alliance with either the SPD alone (his preference), the SPD and the Greens, or (if they reach the 5% vote share required to enter parliament) the SPD and the FDP.

But despite the fact that the AfD will not be part of the new governing coalition, and that the CDU is almost certain to retake the Chancellorship for the first time since Angela Merkel’s sixteen year stint in the job from 2005-21, there is already a palpable sense that the centre right is about to win a Pyrrhic victory. By promising to enact right wing policies while ruling out co-operation with the only other right wing party projected to be in the next parliament, Merz has likely set himself up to fail once in office. Given the steady rise of the AfD’s vote share, the growing anger and desperation of German voters at their political establishment, and the prospect of four more years of ineffectual coalition government amidst mounting internal and external crises, there is now every chance that the AfD could become strong enough to break apart the anti-populist cordon sanitaire by the next election in 2029. What explains their rise, and how will this election affect their prospects for further shaping the country’s political landscape between now and then?

What’s Fuelling the Rise of the AfD?

The AfD was formed in 2013 by Eurosceptic economists opposed to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s approach to the euro crisis – indeed its name, Alternative for Germany, was chosen as a response to her claim that there was “no alternative” to bailing out Greece. Given overwhelming public support in Germany for remaining in the EU and the Eurozone, it struggled until the 2015 migrant crisis, when Angela Merkel threw open Germany’s borders to over a million Middle Easterners, mostly young men. From this point on it reinvented itself first and foremost as an immigration restrictionist and anti-woke party. In the election two years later, it got into the Bundestag for the first time and, after Merkel formed her fourth grand coalition with the SPD, became the leading opposition party. In the federal election after that, in 2021, it received just under 13 per cent of the vote.

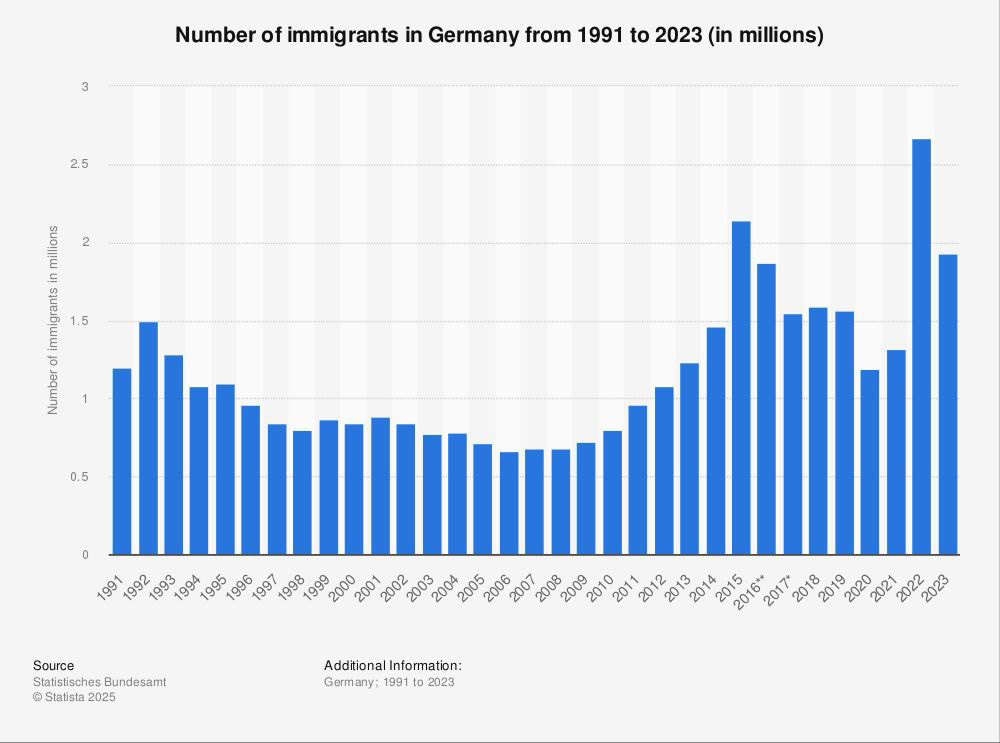

Two major factors since then have pushed its support over 20 percent in the national polls, and as high as 32 percent in state level elections in Thuringia last year. The most important is continuing runaway mass immigration, especially from outside the EU. Although numbers have receded since their peak under Merkel, they remain at historically very high levels, as you can see below. In 2023, around 1.9m people immigrated to Germany, while 1.27m people emigrated, resulting in a net immigration of some 663,000.

The costs of this demographic tidal wave have been heavy. With higher rates of unemployment among those born outside the EU alongside lower average incomes, the situation has worsened the country’s public finances. A leading German academic on public finances resultantly found that the future financial gap between welfare state liabilities and revenues would shrink from €19.2 trillion down to €13.4 trillion, or by €5.8 trillion, if it closed its borders to immigration entirely, contrary to claims that such migration is needed to sustain the welfare state. This is perhaps unsurprising given that data from the German government shows that many of the migrants who arrived in 2015 and 2016 featured low skill-sets, and the majority of them remained long-term unemployed or “looking for work” many years after their arrival.

The influx also had a negative impact on Germany’s educational performance. Although native German children are also performing worse in school tests for literacy and mathematics than they did before the Covid pandemic, children with an immigrant background – who now make up a remarkable 38% of elementary school students – are performing even worse. This has led to a widening educational gap between these groups, which has not been helped by the low skilled nature of much of the immigration in question.

Germany has also seen crime surge since 2015. As I noted in a previous post, data from the German police for 2023 shows that despite constituting 18.4% of the population, non-citizens account for 41.1% of all criminal suspects. For many of the most serious violent offences, the proportion was even higher: they were the suspects in 43.1% of murders, 74.5% of robberies including murder, 44.4% of manslaughter cases, 46% of aggravated rapes, 59.5% of forced prostitution, and 66.7% of serious bank robberies. With respect to asylum seekers in particular, data from the BBC revealed that, as of 2017, they constituted 2% of the population yet accounted for 10.4% of murder suspects and 11.9% of those suspected of sexual offenses.

This latter problem has been front and center in the election campaign, which in turn has helped migration to eclipse every other issue. Since Chancellor Scholz called the election in December, six people were killed and nearly 300 injured when a Saudi migrant ploughed his car into the crowds at Magdeburg’s Christmas market. A month later, on January 22, in the Bavarian city of Aschaffenburg, a failed asylum seeker from Afghanistan attacked a group of kindergarten children in a park with a knife. Two were killed (including a two-year-old) and three injured. The series of migrant murders continued this month: on February 13, an Islamist-motivated, seemingly integrated Afghan bodybuilder steered his car into a left-wing demonstration in Munich, killing a mother and her two-year-old child. On February 15, a young Syrian in Villach, Austria, apparently with Islamic State links, killed a 14-year-old boy with a knife and seriously injured five other people. The perpetrator was pictured beaming with delight after the attack.

The result has been a hardening of public opinion. In a survey last July an absolute majority of 52% agreed with the statement that “Germany should generally no longer accept refugees from Islamic countries”. There was even greater agreement, by 57% of respondents, with the statement that “in certain areas of my town or village, I have the feeling that I am no longer in Germany”. The poll also showed that 54 percent of respondents said they were “afraid that Germans will become a minority in Germany”, which if present trends continue will occur around the 2060s. In the aftermath of another knife attack by a Syrian refugee in Solingen in August in which three people were killed and eight injured, another poll revealed that 45 percent of the population “fully support” closing Germany’s borders. Six months and four attacks later, the support has grown to two-thirds.

Most of the AfD’s electoral success is due to this deepening dissatisfaction with German immigration policy. It fills a clear gap in the political marketplace as the only party explicitly to take restrictionist positions despised by all the establishment parties, with the partial exception of the small paleo-leftist BSW: maintaining the primacy of German language, culture and identity instead of multiculturalism; encouraging increased family formation and productivity among Germans rather than relying on mass immigration; stating that “Islam does not belong to Germany”; and, in its latest election program, explicitly calling for “remigration”, as AfD leader Dr Alice Wiedel did at the AfD conference in Riesa, Saxony recently. This latter concept encompasses perfectly reasonable measures such as deportations of illegals, extremists, criminals and refugees from safe countries back to their homelands, as well as expanding incentives for voluntary return by others. This didn’t stop the media launching a smear campaign against it starting in January 2024, after reports of an allegedly secret “far-right meeting” which they absurdly compared to the Wannsee conference, but their tactics backfired. The main effect of such hyperbole about a meeting to discuss options for peaceful remigration was to make the idea mainstream; since then it has been used by Donald Trump and is now government policy in Sweden.

The problem of mass immigration and its collateral damage is, of course, now an urgent one in all Western European countries. Even Mr. Merz, whose own CDU party under Mrs. Merkel opened the floodgates in 2015, now recognizes that he must strike a restrictionist pose if he is to beat the AfD. The day after the attack in Aschaffenburg, he rejected Mrs Merkel’s legacy by announcing: “If I am elected chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, using the chancellor’s power to issue directives, I will, on my first day in office, order the federal ministry of the interior to permanently control the German state borders with all our neighbors and to reject all attempts at illegal entry without exception.”

The issue caused a serious crack in the cordon sanitaire of the mainstream parties against the AfD when Mr. Merz agreed in the wake of the attack to accept the right populists’ votes in support of a non-binding “five-point” plan “for secure borders and the end of illegal migration.” “The firewall has fallen!” Ms Weidel wrote on X. “That is good news for our country!” This made Mr. Merz himself a target of ‘anti-fascist’ demonstrations and a ‘Rebellion of the Decent’ by protestors in Berlin, as well as earning him an unprecedented rebuke from Mrs Merkel (who demoted him and pushed him out of politics twenty years ago). He lost what was left of his party’s credibility on the issue when he later declared that he would never “sell the soul of the CDU” by working with the AfD again, leaving him with no plausible parliamentary route to a majority for such tough measures.

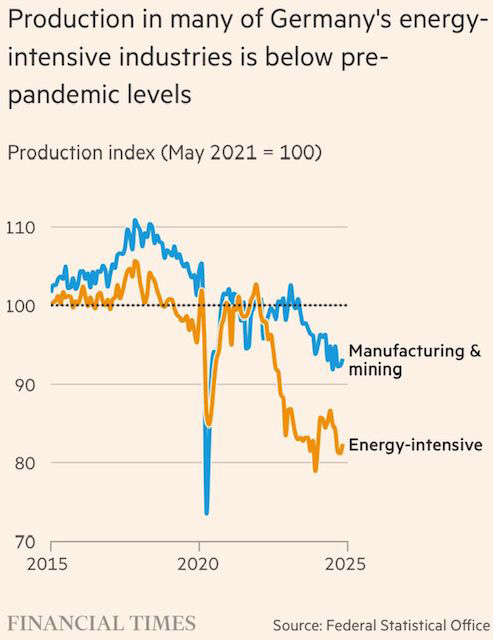

Aside from immigration, the other major issue likely to be on the minds of AfD voters on Sunday is economic stagnation. The German economy has grown by a meagre 0.1% over the past five years and is, according to forecasts, now entering yet another year of stagnation. This has been a major blow to the living standards and self-image of a country that had gotten used to being admired as the economic powerhouse of the Continent. And whereas the country has been in a similar situation before, in the early 2000s, this time around the challenges are even more daunting. America, once keen on trade liberalisation, is threatening 20% tariffs on EU exports. China, formerly an enthusiastic purchaser of German equipment, now mostly makes its own. And worst of all, the country’s energy intensive heavy industries have been badly affected by the twin blows of the Ukraine war (which made cheap Russian gas unavailable) and Angela Merkel’s decision to shutter Germany’s nuclear reactors (the last three of which were deactivated with impeccably bad timing in 2022, just as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine got underway). You can see the unhappy results below. As a party that favours diversifying the country’s energy sources to include more nuclear and fossil fuels, and which has long favoured a negotiated settlement to the war, the AfD’s offer of faster growth via cheaper energy has made it well placed to win over new supporters on pocketbook issues as well as demographic and cultural ones.

Looking Ahead

Despite these powerful tailwinds in its favour, the AfD will probably come second to the centre-right Christian Democratic Union on Sunday. It will not enter government, as no other party will presently join a coalition with a party that the political establishment continues to smear as extremist. But the AfD’s leader, Alice Weidel, intends to become Germany’s chancellor in the election after that, which is due by 2029. In the meantime there are at least two good reasons to expect it to continue reshaping German politics and setting the agenda.

The first is that although Mr Merz has tacked right, he will probably have to govern with one or more leftist parties in coalition. That means he will be unable to deliver his promised policies, such as rejecting asylum-seekers at Germany’s borders, returning to nuclear power, postponing net zero, deregulating or simplifying the tax code. Assuming his party gets around 30% of the vote but needs at least 45% of Parliament to legislate, there is no scenario, barring a colossal polling error, that would allow the CDU to enact these AfD-lite policies when it is committed to excluding the only other Right-wing party in parliament. The pro-business Free Democrats are currently polling at 4%, which would mean zero seats. The other remaining parties are from the Left, none of which exceeds 5% support either. If he sticks to his promise not to rely on the votes of the AfD, this means Mr Merz will have to abandon or dilute every major promise he has made on the most important issues, leaving a lot of his former supporters disappointed and the country’s problems unresolved.

This betrayal will moreover take place in a country where voters have become deeply pessimistic and jaded about their political establishment. Just 22% of Germans think the country is “up to the challenges of the future”. The constant in-fighting of the outgoing “traffic-light” coalition has left them sick of incoherent multi-party governments. This is the first election since records began in which every leading candidate has a negative approval rating, and just 25% of Germans say they are satisfied with Mr Merz. And despite being favoured to win, his party is still on track for the second-worst result in its history, and his likeliest coalition partner, the SPD, for the worst result in theirs. Add all this together and where will disappointed voters turn when the next elections take place if Germany’s immigration and economic problems haven’t been fixed?

The second factor working in the AfD’s favour is developments abroad. Nearly everywhere in the West, the neoliberal/neoconservative centre-right is being replaced by national populists as the main right wing political force. National conservatives are already in government by themselves or in coalition in Italy, Hungary, Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands. In France, Marine LePen is presently favoured to win the next French presidential election. In Romania, a traditionalist nationalist candidate won the first round of the presidential election last December, only for the result to be annulled by the country’s Supreme Court; he has since soared by a further twenty something points in polling ahead of fresh elections in the spring.

The latest victim of this civilisation-wide vibe shift is the world’s oldest political party, the British Conservatives. The Tories, who quadrupled net immigration when they ruled Britain from 2010 to 2024, are now even worse off than when they failed to break 25 per cent in the popular vote in last year’s general election, falling to third place in recent polls. This is not because the Labour government has succeeded – on the contrary, Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer is deeply unpopular – but because Nigel Farage’s Reform UK party have soared into first or second place due to a familiar mix of complaints: unprecedented levels of immigration, radical demographic change, woke censorship, DEI discrimination, expensive energy, and sluggish growth. With Britain’s establishment parties unable or unwilling to credibly address these issues, voters are turning elsewhere instead.

Most significant in this regard, of course, is the support offered to the AfD by the newly reelected Trump-Vance/Musk alliance. Elon Musk started this off with a widely discussed “hangout” on X with Alice Weidel, which brought her a lot of international publicity and helped counter her pariah status in the German business community. At a subsequent AfD party conference in Halle, Mr. Musk surprised everyone by delivering a message via live broadcast in which he called on Germans finally to leave Nazi era “guilt” behind and vote for the AfD, who alone he said could now “save Germany”.

Vice President JD Vance also spoke out in favor of the party’s policies at the Munich Security Conference last week. He deplored mass immigration to Europe as well as the suppression of free speech to censor its critics: “I believe that dismissing people, dismissing their concerns or worse yet, shutting down media, shutting down elections, or shutting people out of the political process protects nothing,” he said. “In fact, it is the most surefire way to destroy democracy.”

He then directly addressed the practice of quarantining the AfD: “Democracy rests on the sacred principle that the voice of the people matters. There is no room for firewalls. You either uphold the principle or you don’t.” The government parties as well as the CDU reacted by immediately condemning Vance’s speech as “unacceptable,” thus proving his point.

First Austria, Next Germany?

Mr. Musk doubtless exaggerated the importance of Sunday’s election in his televised speech to the party conference when he said, “I think it could decide the entire fate of Europe, maybe the fate of the world.” This is not yet such a monumental fork in the road. Nonetheless, this election may at least be one step closer to an urgently-needed change of German and European policies, and it is increasingly clear that can be achieved only through the AfD. If they are the only party that wants to govern in a right-wing fashion in response to the challenges of this era, and bringing them in from the cold is the only way of reaching a parliamentary majority for this purpose, voters are likely to eventually agree to give them a try.

This might currently seem far-fetched given the anathematisation of the party by the German and international press, but this is what happened next in Austria. In 2019, the conservative People’s Party (ÖVP) gained over 37% of the vote, while the populist right Freedom Party (FPÖ) came in third with 16%. After the conservatives entered a coalition with the Greens, their approval rating collapsed and they fell behind the Freedom Party in the next election. The populists duly stormed to victory with almost 29% of the vote in last September’s vote, leaving the country on the verge of its first FPÖ chancellor ever since, although negotiations remain ongoing.

The CDU today is in a similar position to the People’s Party then, and if Mr Merz governs with the left for the next four years as he intends, they may well find themselves facing a similar fate in 2029. The erosion of the anti-populist firewall in the meantime is likely to manifest at the state level first. It is most at risk in the east, where a new CDU-led minority government in Saxony may fall apart, and where elections next year in Saxony-Anhalt, a populist stronghold, will probably yield a victory for AfD. At the federal level their task will be harder, but if Mr Merz and his aides find themselves failing to get on top of Germany’s problems, especially mass immigration and economic stagnation, the AfD could well follow their Austrian counterparts to a first place national finish in the next election.

Comments (1)

Only supporting or founding members can comment on our articles.